Flipped or tilted? Professors use technology to engage students

By Sydney Worth

It was 1998. Bill Clinton was president, cell phones resembled large bricks, and the Denver Broncos beat the Green Bay Packers in the Super Bowl XXXII.

At the University of Colorado, physics professor Steve Pollock was looking for a way to check the students’ comprehension and at the same time integrate then-current classroom technology. His solution: colorful notecards. Pollock, a 2013 Carnegie Foundation U.S. Professor of the Year, gave his students a question and asked the students to indicate their answer by raising one of the five notecards he distributed.

Fast forward to 2003. George W. Bush called the White House home, the BlackBerry was released, the Tampa Bay Buccaneers actually won a Super Bowl, and Pollock introduced infrared clicker technology in his classes. The clunky receivers that went with these updated notecards provided more problems than they solved, though.

[video:https://youtu.be/U1WZw1RLTVQ]

In 2007, CU introduced iClickers in a time of iPhones, two U.S. wars, and a fifth Harry Potter book. Pollock embraced the new clickers.

Seven years later, he’s still using them.

“We spend a lot of class time letting students think and talk, so at any level [of physics], I will have clicker questions,” Pollock said.

Even with his enthusiasm, Pollock isn’t quick to see educational technology as a solution for all of the difficulties in teaching and learning.

“Technology isn’t an end. It’s a means to an end of learning, students learning,” he said.

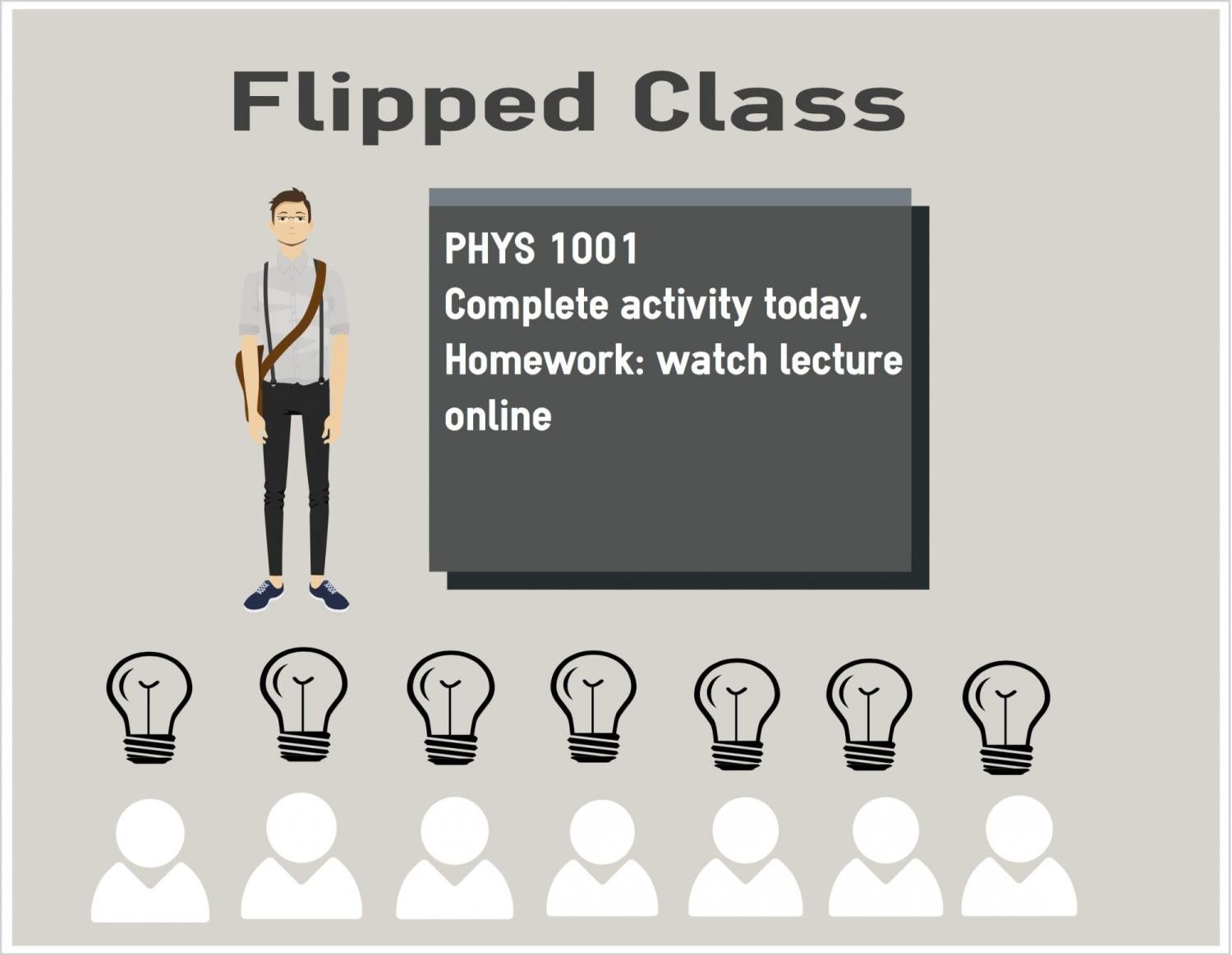

Professors such as Pollock are part of a wave of CU instructors who have employed new technological tools to enhance their classrooms. This growth in technology has allowed the “flipped classroom” to develop the classroom into an entirely new shape. Students now have the opportunity to watch video lectures at home and professors the ability to create a more engaging lesson for their students.

Two Colorado high school chemistry teachers are at the forefront of the flipped revolution. Jonathan Bergmann and Aaron Sams from Woodland Park High School have written two books on the subject in the last two years.

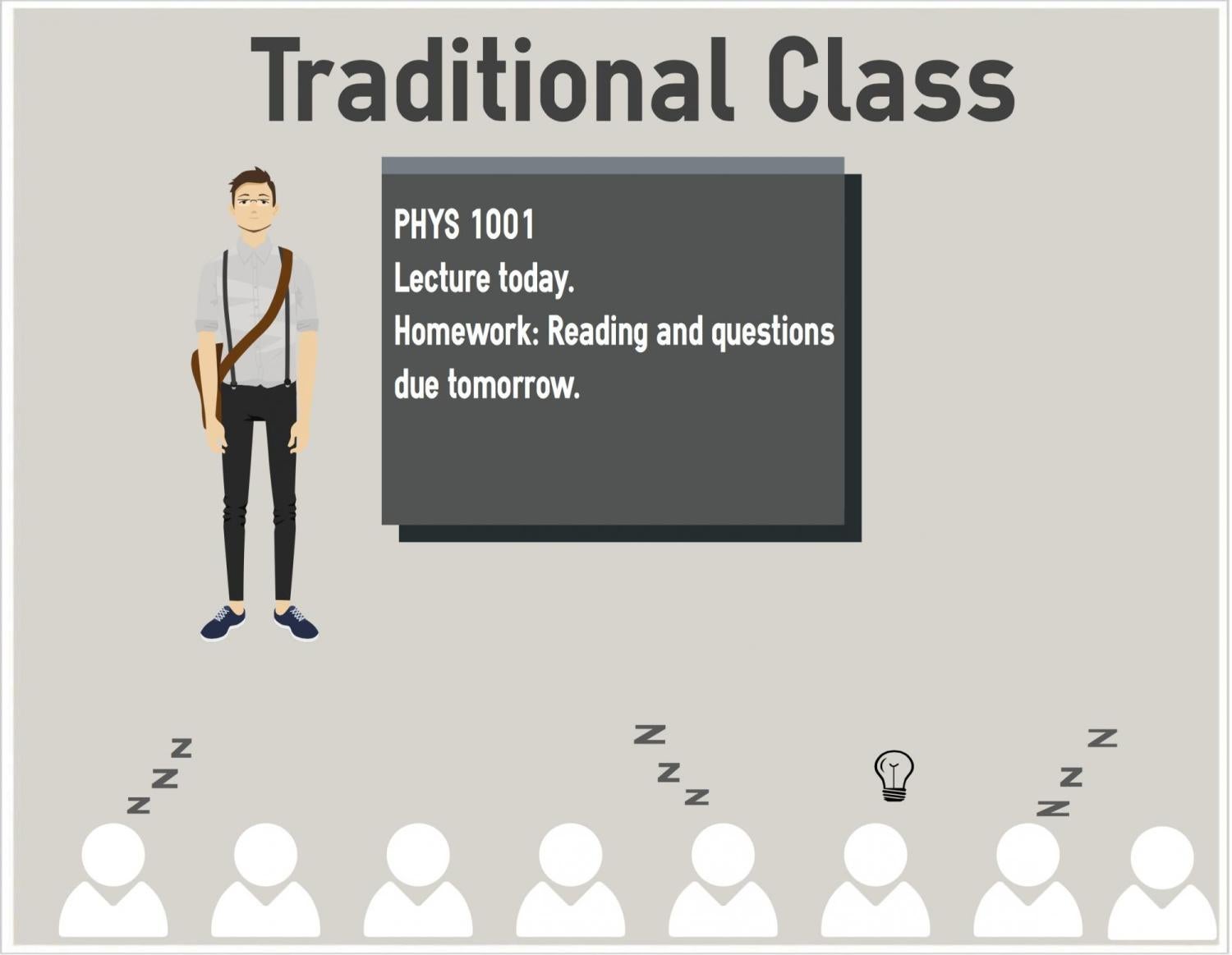

In a video on his website, Bergmann describes his vision: “I think we’re moving from this classroom, this teacher-centered classroom, to this active, engaged, problem-centered, challenge-based, inquiry-driven classroom of the future.”

Pollock isn’t so convinced of the flipped classroom. He believes that the main goal of a flipped class is to feed students the idea that it isn’t advantageous to sit through lectures.

“What [students] could really be doing is getting feedback from the professor,” Pollock said.

CU OIT Program Manager Aisha Jackson says that half of the university’s 5,000 courses are on Desire2Learn, a course management system developed by a private company and contracted by CU.

“So they like standing in front of a room, and having lectures, and reading assignments,” said Larry Levine, assistant vice chancellor for IT, “and whatever the nature of the course is — a lot of the classrooms are completely flipped.”

Lead Instructional Designer Debra Warren is just as aware of the rising popularity in educational technology.

“I think that with technology in general, there’s so much rapid change. We’re just going to have to wait and see what happens,” Warren said, “There are going to have to be Beta testers willing to try things out.”

Warren mentioned some benefits of having a flipped class such as helping quieter students form their thoughts, minimizing space issues, and making it so weather isn’t as much of a problem.

“When we had the floods last September,” Warren said. “I had one instructor emailing me because he wanted the lectures up and available so if students had access to the internet, they could keep going with the class.”

Philosophy professor Sheralee Brindell is just as confident about the growth of flipped classrooms.

Brindell spoke about her goal to make more use of Desire2Learn in the hopes of creating more convenience for both herself and her students.

“I can do various things without having to worry about getting some graduate student to mind my course,” Brindell said. “If I can’t get someone to take over for me, then I have to cancel class. That makes it feel as though that if I have to cancel class, then I shouldn’t be doing the thing that I’m wanting to do.”

Even with the helpful aspects of software such as D2L, Brindell can name some drawbacks. D2L’s format limits the instructor’s creativity.

“There’s quite the straitjacket in D2L,” she said.

Unlike Brindell, Pollock doesn’t make as much use out of D2L, but he builds class websites outside the D2L platform. He also said he “tilts” his classroom rather than seeking to flip it completely. However he designs a class, though, Pollock said the key is to get students engaged during class time and at home.

“What I want is a nice, student-driven set of ideas where people can talk about where they went to figure out the problem,” Pollock said, “or what the underlying physics was they used to figure out the problem.”

The idea of making videos and uploading them is something Pollock claims to have no time for, and that is a problem that most professors acknowledge as being a major hurdle in creating a completely flipped class.

However, some secondary schools have begun to create video repositories, so professors and teachers aren’t constantly having to create new materials.

“Once we create them, we have them forever,” a New Jersey educator said in a 2001 article in Harvard Education Letter.

For Pollock, feedback and discussion are incredibly important in his classes, and he makes use of the iClickers to get just that.

“The problem with clicker questions is it looks like it’s a quiz, but that’s not the idea at all. We really want it to be a discussion,” Pollock said.

Pollock also said that while some aspects of technology may be useful, the traditional textbook may be the most useful in the end.

“I’m teaching a lot of upper-level division physics. It’s very technical and very advanced. Many of them are quite capable of reading the textbook and learning an awful lot on their own,” Pollock said. “The lecture itself is maybe not still the central ingredient; it’s the opportunity to argue and think.”

Pollock believes that incorporating methods that engage students, whatever that may be, is ultimately the most important thing when teaching.

“I think we want to make use of technologies that really can demonstrably help students to learn and have fun while they’re learning.”