Closing the gap with distance learning

Distance learning, MOOCs and the traditional college classroom

By Muzette Mercer

Sitting at a local coffee shop, students stare at their laptop screens and listen to their earphones while sipping on chai tea. Despite appearances to the contrary, these students are in class; they are distance learners.

CU-Boulder and other higher education schools have joined the national trend of online and distance learning. However, as the fad becomes more popular and technology changes, there is rising controversy about the problems seen within the online courses.

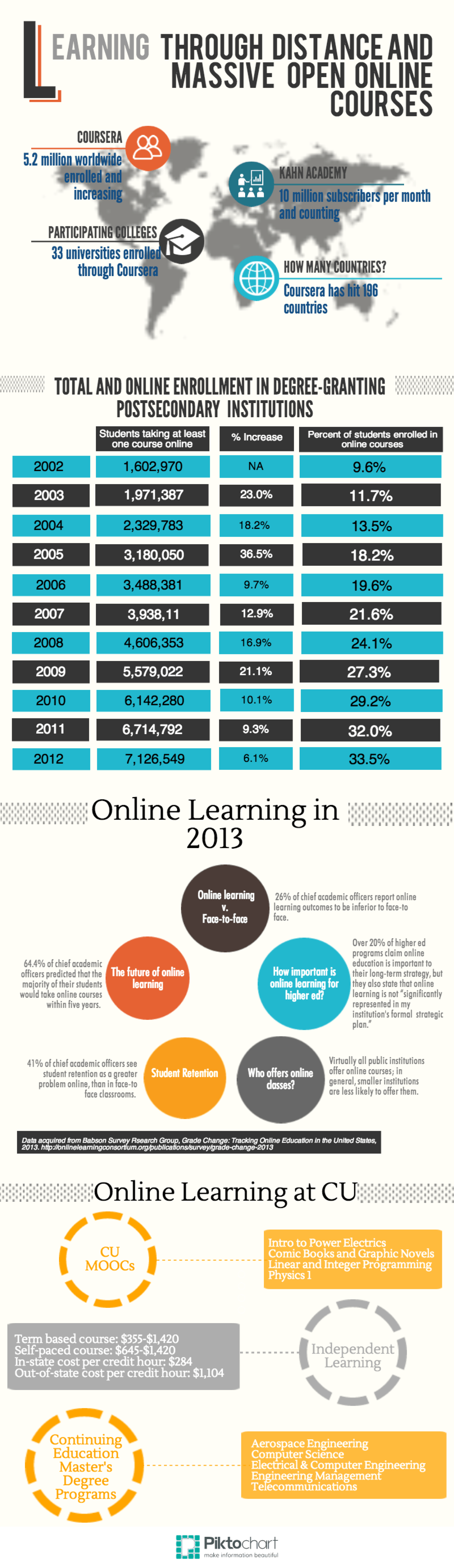

Over the last decade, online classes and E-Learning (electronic learning) have grown significantly. According to Babson Survey Research Group, over seven million students enrolled in online courses during 2012. These students represented a 6.1 percent increase in online enrollment over 2011.

These numbers signify the growing emphasis universities are placing on online education. Larry Levine, associate vice chancellor for IT at CU-Boulder, states that the two primary missions in creating a tech-based environment for online learning are providing “computing or information technology in support of student learning and faculty teaching, and in support of faculty and people associated with faculty conducting their research or creative works.”

“One of the hopes is that online coursework can help solve the crisis in higher education: affordability and easy access,” said CU’s director of independent learning, Geoffrey Rubinstein.

While we see increases in online enrollment, distance learning has been transforming education for more than a century. The California Distance Learning Project credits Isaac Pitman as an early pioneer in distance learning during the 1840s. During the 20th century, radio and television offered new media for educators to reach students; in addition, “with the spread of computer-network communication in the 1980s and 1990s, large numbers of people gained access to computers linked to telephone lines, allowing teachers and students to communicate in conferences via computers.”

However, according to Babson, 26 percent of chief academic officers in 2013 continue to consider online learning inferior to face-to-face education.

Nevertheless, from the campus of University of Colorado Boulder to the villages of South Africa, students and professors continue to adapt technology for education despite the lack of intimacy gained in face-to-face education. Iris Ebert, a student at CU-Boulder, likes her current online course because it works around her schedule, but she admits that she has not met the professor in person. She does feel that “being able to have the lectures to go back and reference, and getting to complete the course in a shorter time than a regular semester course” outweigh this lack of personal connection.

New technological tools can also contest the lack of intimacy between students and teachers through audio recording, Skype, and even Google Hangout. These advances enable students to have a voice in their online discussions at their own convenience, and may even lead to more discussion than the instructor might see in a traditional classroom setting.

Additionally, MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) provide a free education for anyone interested in a given topic. MOOCs are non-traditional, online courses aimed at providing world wide access to knowledge through the Internet. Often these courses are offered free through services like Coursera and EdX, but participants receive no academic credit.

In fact, Laura Pappano dubbed 2012 “The year of the MOOC” in the New York Times. However, as Rubinstein notes, MOOCs “have been following what is known as a hype curve, which is something that gets a lot of buzz. It’s ‘going to change everything’ until it doesn’t change everything and it starts moving down the curve into what is called the trough of disillusionment.”

Despite the influence of MOOCs over the last several years, Rubinstein doubts the longevity of their usefulness.

While many MOOCs remain unaccredited, online courses offered through universities are often applied toward students’ graduation requirements. Students who are working to raise their GPA or study abroad can still progress toward their degree despite their location. CU Professor Paul Voakes, Ebert’s instructor, adds, “My course is already pre-recorded basically. So, a student who is on a full-time internship or working a summer job, and who could absolutely not be on campus, can still take the class and accelerate the degree program.”

At CU-Boulder, the Continuing Education Department provides a variety of online courses. Given the rapid rate of technological development, it is often difficult for instructors to keep up with educational trends that involve emerging technologies. However, administrators like lead instructional designer Debra Warren work with instructors and content experts to develop online courses, including face-to-face classes, to CU’s online learning environment.

“There’s always new technology to choose from,” Warren said, “ but before we incorporate it into courses we encourage instructors to evaluate it based on how well it will help students learn.”

Rubinstein also notes, “Compared to face-to-face courses, our online courses are intended to be equally rigorous, equally challenging, and equal in the amount of work that is demanded of students in higher education.” Any students who have access to the web can now have the same education as if they were studying on-campus, Rubenstein said.

Likewise, Aisha Jackson, program manager for teaching and learning applications with the Office of Information Technology at CU-Boulder, argues that MOOCs are “even better in some ways, because the teams that helped to build those spaces are more robust than you might see in other classes.”

Since the development of the web, universities have transformed traditional pen-to-paper classrooms into digitized text and lecture. When administrators, instructors, and media developers all collaborate for online classes, they can present dynamic new educational opportunities, which can progressively evolve to be revolutionary.