Spilling the Beans in Two Languages: Idiom Processing in Bilinguals - by Anna Hoisington

“Have you wondered why some idioms just don’t make sense in another language – even if

you’re fluent?”

By: Anna Hoisington

Course: LING 4100/5100: Perspectives on Language: Language and Embodiment

Instructor: Professor Bhuvana Narasimhan

LURA Nomination: Professor Bhuvana Narasimhan

Idioms: More Than Just Words

Idioms are quirky, playful, and sometimes downright strange and that is exactly what makes them so fascinating. Expressions like “spill the beans” or “estar en las nubes” (“to be in the clouds”) don’t translate literally, which can make them challenging for language learners to understand. What if the way our bodies experience the world could actually help us make sense of these obscure phrases?

For my honors thesis in Linguistics at CU Boulder, I conducted a pilot study to explore how bilingual English and Spanish speakers process idioms in their second language. My project looked at how language proficiency, exposure to the second language (L2), and embodied meaning (or meaning tied to physical sensation or experience), influence idiom comprehension. My guiding question: Can embodied imagery make idioms easier to understand across languages?

Transparent, Opaque, and Everything in Between

There are two key types of idioms in this study:

Transparent idioms are somewhat easier to understand because they hint at their meaning through metaphor or context. For example, “foot the bill” might evoke the idea of paying at the

bottom (foot) of a restaurant bill—there’s a loose connection, even if it’s not literal. Opaque idioms, on the other hand, offer few contextual clues and are typically more difficult to interpret, especially for second language learners. “Spill the beans” has nothing to do with actual legumes.

Idioms also vary in embodiment—that is, how much they evoke a physical or sensory experience. For example, “roll up your sleeves” is grounded in bodily action, while “to change one’s mind” is more abstract and lacks a clear physical correlate.

I was curious to see whether idioms with more embodied elements would be easier for bilingual speakers to understand, regardless of how long they had been speaking the language.

How I Ran the Study

Participants in my study were either native English speakers or native Spanish speakers who had acquired their second language to varying degrees. I gathered 28 participants in total, 14 of which were native English speakers and the other 14 were native Spanish speakers. Each participant completed:

1. A background questionnaire assessing their language history, self-reported proficiency, age of acquisition, and frequency of use in both languages.

2. A comprehension test with 14 idiomatic phrases (7 in English and 7 in Spanish). Idioms were selected based on their transparency/opacity, embodiment level, and grammatical structure.

3. A confidence rating for each idiom (1-7 scale), demonstrating how sure they were of their interpretation.

Each idiom was presented in the participant’s second language, and responses were collected to determine both accuracy and confidence across idiom types.

Example stimuli included:

● English: “Bite the bullet,” “Break the ice,” “Shoulder the burden”

● Spanish: Estar como un flan — ‘to be like a flan’ (i.e., shaky/jittery, meaning nervous)

● Tener un buen ojo — ‘to have a good eye’ (i.e., to have a good eye for something; translated more clearly as “to have a good eye for detail”)

● Levantar cabeza — ‘to lift one’s head’ (i.e., to recover/improve one’s situation)

My Findings:

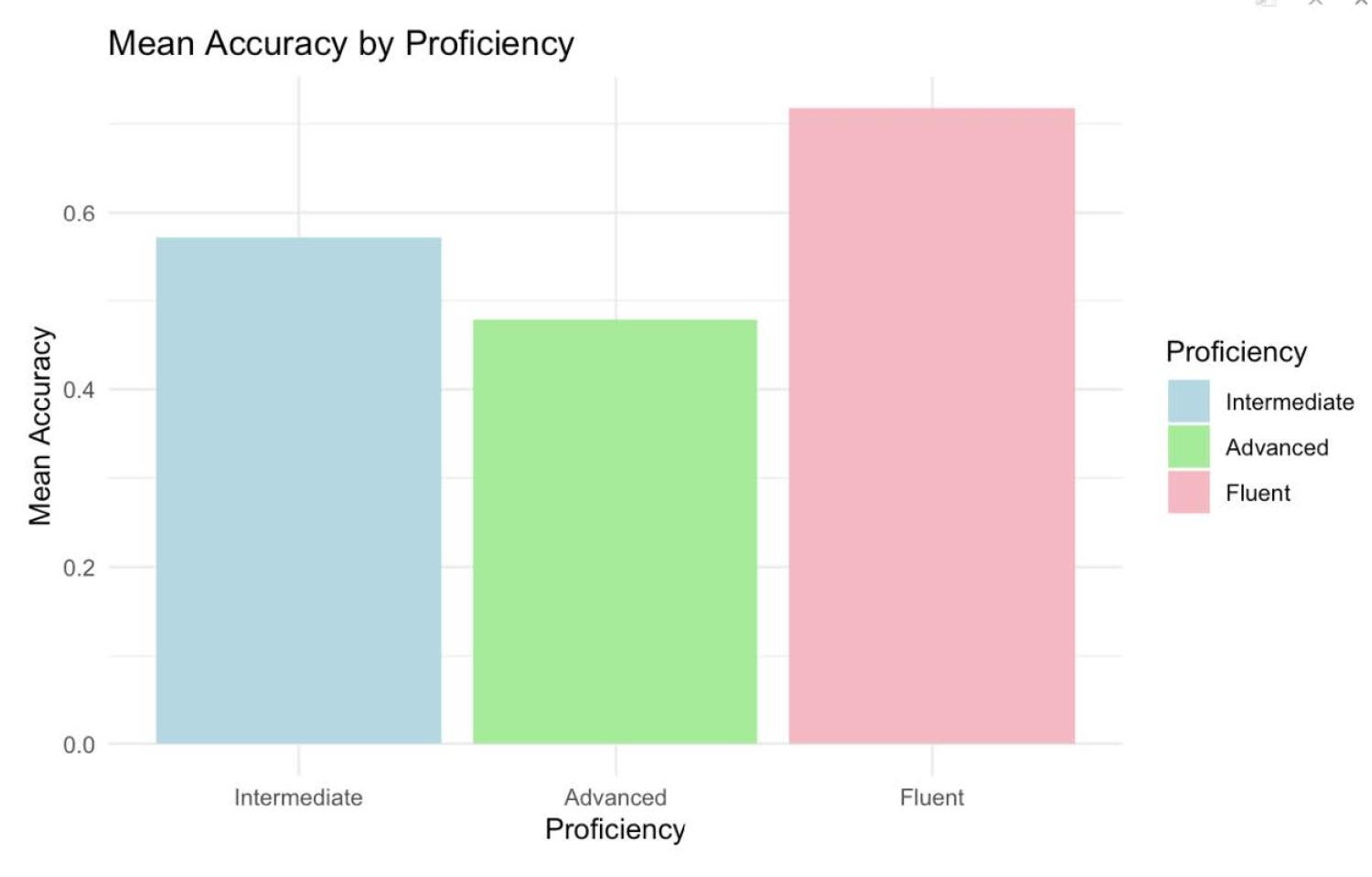

My results indicated that language proficiency had the strongest effect on idiom comprehension. Fluent speakers outperformed intermediate and advanced speakers, with accuracy rates over 70% in both groups. This supports the idea that a higher command of the language leads to better understanding of idioms, regardless of the type.

Contrary to my expectations, embodied idioms were not interpreted more accurately than non-embodied ones. In fact, non-embodied idioms were slightly easier to understand across both English and Spanish speakers.

Regression analyses also showed that proficiency and confidence both influenced accuracy, especially when combined. These findings suggest that while embodiment may still play a role in language learning, proficiency and self-awareness of ability are more predictive of successful idiom interpretation. Below, I have included the visual representations of the role in which the speaker’s level of proficiency played in idiom comprehension.

Figure 1.

Mean idiom comprehension accuracy by proficiency level.

Fluent bilinguals achieved an average accuracy rate of over 70%, while intermediate and advanced groups performed lower overall.

Why This Matters

Understanding idioms—and figurative language in general—is essential for achieving fluency and cultural literacy in a second language. Whereas a growing body of work suggests that idioms aren't just arbitrary expressions but are often tied to bodily experiences, my findings highlight that the role of embodiment must be evaluated in conjunction with other factors like language proficiency and speaker confidence.

This has implications for language teaching: if learners connect idioms to embodied experience and develop proficiency through meaningful exposure, instruction could become more effective and memorable.

Where I’m Headed Next

As I prepare to graduate, I plan to continue exploring how language, culture, and embodiment interact — especially in bilingual and second language contexts. This project will serve as the foundation for my honors thesis, and I hope to build on it through future academic or professional opportunities in linguistics. Whether through graduate study or applied research, I’m excited to keep investigating how people create meaning across languages. This project has deepened my belief that idioms are not just linguistic puzzles — they are windows into how we think, feel, and move.