In School, but At Home: the Difference in Meaning

What semantic features distinguish in from at and lead a speaker to choose one preposition over the other?

Vida Alami

Course title: LING 3430: Semantics

Advisor: Prof. Zygmunt Frajzyngier

LURA 2021

Ask an English speaker the difference between in and at, and they might have trouble articulating it. We know that both prepositions relay the static position where something is. We also intuitively know that they aren’t interchangeable. However, the set of contexts where they appear can be very similar. English language learners often memorize a set of seemingly arbitrary rules about when to use in versus at that don’t really explain how their meanings are different.

In this project, I wanted to explore the semantic differences between the English locative prepositions in and at. I developed a hypothesis that “transience”, a term I chose to represent the relative duration of position, is part of the meanings of these prepositions and rationalizes some of their usage patterns.

My analysis began with a sample of 40 spoken utterances from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA), half containing in and half containing at. For each utterance, I substituted one locative preposition for the other–replacing at with in and vice versa–while keeping the rest of the utterance constant. I then evaluated any changes in meaning or grammaticality that resulted.

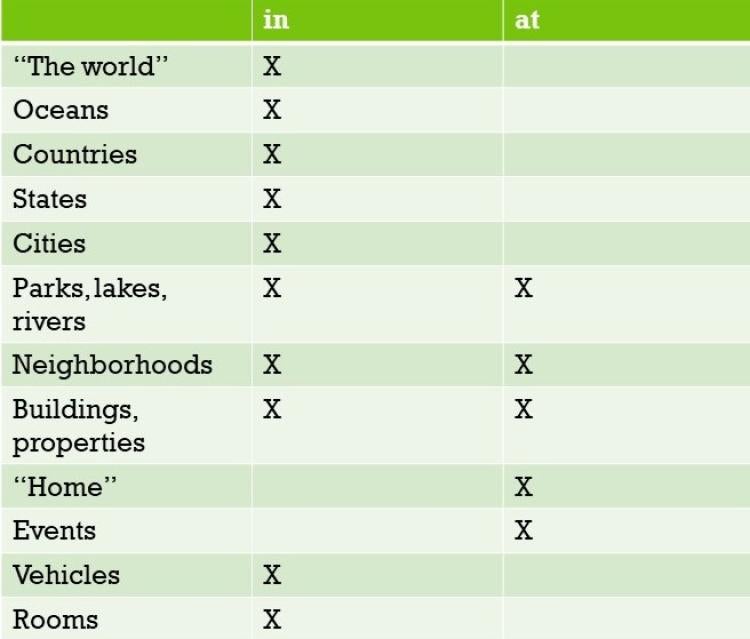

What I found aligned with the Oxford Guide to English Grammar’s claim that two factors, dimensionality and size, partly distinguish in from at. In is for 3-D, enclosed spaces and large areas. At is for 1-D points in space and smaller areas (Eastwood, 2005). Table 1 displays this pattern in the preposition distribution for some typical location nouns. In the examples below, the first sentence is the original utterance and the second is with preposition substitution. Ungrammaticality is marked with (*).

- In the last forty years, we’ve had growing inequality in this country.

*In the last forty years, we’ve had growing inequality at this country.

- I'd sit in my room for days at a time and just kind of be there.

*I'd sit at my room for days at a time and just kind of be there.

All example data comes from COCA (Davies, 2008-).

In (1), country is a large area that rejects the use of at. In (2), room is a necessarily 3-D, enclosed object that also is incompatible with at because their dimensionalities conflict.

Table 1. Sample of typical complements of locative prepositions.

The original hypothesis I developed during my analysis is that transience also influences the usage of in versus at. Transience has to do with how permanent X’s position relative to Y is in the construction “X in/at Y”. Being at a place implies that you’re there temporarily. When you’re in a place, on the other hand, the duration of the spatial relationship is more long-term. Take these examples:

- Well, I think it was just so late at night and he was seventeen, still in school.

*Well, I think it was just so late at night and he was seventeen, still at school.

- Frustrated after being ignored by girls at a party, he tried to shove them off a ten-foot ledge.

*Frustrated after being ignored by girls in a party, he tried to shove them off a ten-foot ledge.

We see that in codes something lasting about the relationship of X and Y. Saying that someone is “in school” (3) typically codes their status as a student regularly attending school. “At school” instead suggests being physically present on the school campus. In (4), a switch from at to in changes the reading of the word party to mean a group, of which the girls were members. A party, in the sense of a celebratory event, is inherently temporary. This mismatch between the duration of a party and the duration coded by in triggers the meaning change.

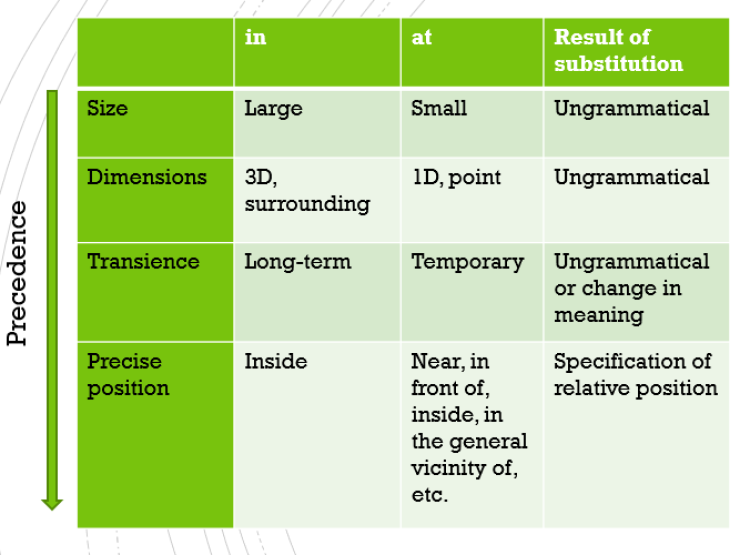

Table 2. Hierarchy of characteristics that distinguish in from at.

At the end of my analysis, I proposed that English speakers evaluate a set of semantic features in a specific order when choosing between in and at, summarized in Table 2. Because dimensionality and size have strict grammaticality boundaries, they come first. Transience follows, and the speaker chooses whichever preposition matches its complement’s transience to communicate a specific meaning. Finally, the choice between in or at can act as a fine-tuner for describing position.

Research on this topic may continue with an investigation of whether and how the spatial meanings of in and at relate to their meanings as prepositions of time.

Bibliography:

Davies, Mark. 2008. The Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). Available online at https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/.

Eastwood, John. 2005. Oxford Guide to English Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.