History of Yiddish in American English

My family’s immigration and the integration of Yiddish into American English.

Drew Brian Frank

LING 1000 (Language in US Society)

Advisor - Natalie Grothues

LURA 2021

During the nineteenth century, the growth of anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe sparked a movement of Jewish emigration; between 1877 and 1917, around 2.5 million Jews reached the shores of America, barely escaping worsening persecution, segregation, and eventual execution from the Nazi Party. These immigrants brought Yiddish culture to America. Upon their arrival, these Jewish immigrants struggled but felt they had to refrain from using Yiddish in public situations. However, these immigrants used Yiddish words when speaking English, and eventually, these Yiddish words spread into the general American English lexicon. Experts believe the reason Yiddish made such a prominent presence in English is due to its unique ability to express abstract feelings in one- or two-word phrases that normally require a wordier alternative (Fishman, 1957).

My family has close ties to the growth and preservation of Yiddish culture in America; I’m here today because my mother’s family escaped the Nazi invasion of Poland. Luckily, just before World War II, my great-grandparents, Zelig and Rebecca, and grandpa, Abi, migrated from Poland to Finland, staying there until the war ended. After the war, they left everything they had, in the hopes of a fresh start in America.

Upon arrival in America, fitting in was difficult since they spoke no English. Zelig and Rebecca were much older and had trouble communicating in English. They had thick Yiddish accents and had trouble pronouncing [w], which they pronounced as [v], pronouncing ‘which’ more like ‘vitch.’ Abi was 12 years old when they immigrated to America and went to an English-speaking school. He was placed three grades lower than his age level to help him learn English, but he was picked on because he looked and talked differently than his classmates. But as time went by, they started to better fit into American culture by adapting to new norms.

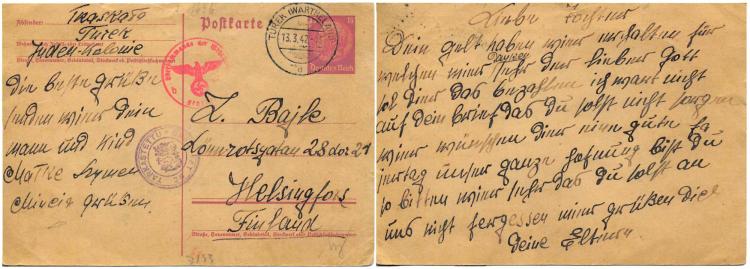

Immigrating to America meant that individuals were limited in the belongings they brought. Zelig remained in possession of two family artifacts to remember their family in Poland. These artifacts remained in the bottom drawer of their desk, never seeing the light of day. This drawer contained an envelope with a picture of Hitler and the ambassador of Finland as well as a golden yellow postcard. The postcard had a swastika over the stamp, which was a sensitive topic that always disturbed them. When anyone went close to the desk, Zelig would blurt out in his Yiddish accent, “Put that away, vhy you need to look at that.” Zelig and Rebecca never talked about their experience in Poland and Finland before and during the war. It was as if Zelig and Rebecca were attempting to erase their prior memories from Europe.

Original Photo of General Mannerheim and Adolf Hitler Scanned for Education

It wasn’t until recently, three generations later, that we were able to dig up the unanswered mysteries about our family’s postcard. It was written in Polish, using Yiddish words, and we were fortunate to find a Rabbi that spoke both languages. We assume my great-great-grandmother, Devorah, did this so the Nazis couldn’t understand the postcard. This was the last letter Rebecca received from her mother before her family was sent to a concentration camp in Poland.

Original Family Postcard from Devorah to Rebecca Bajle - “Dear daughter, your money, we received for which we thank you bless God and you. I do not wait for your letter, so you should not worry. We wish you all the best, you are our only hope, all hope. And we ask…. you not forget about us. We greet you, Your Parents.”

As my family began to settle into American culture, so did their mother tongue. Slowly but surely, Yiddish began to make its way into the English lexicon, exemplifying a reciprocal relationship between the two. This symbiotic relationship was formed through bilingual Yiddish-English speakers living close to monolingual English speakers. Yiddish has been able to fill the need for fresh slang that is fun to say, that also expresses complex concepts that are otherwise expressed in wordy phrases in English. Yiddish is known to add “spice” to everyday conversational speech, which has undoubtedly created an attraction towards Yiddish (Fishman, 1957).

Some examples of English words that derive from Yiddish words include glitch, klutz, bagel, futza, shlemiel, shlump, shnuk, shmuck, schmutz, schlep, shmo, nebish, tuches, klots, yold, bubbe, oy vey, mensch, nosh, putz, mazel tov, and many more (Steinmetz, 1986).

Over the years, Yiddish loanwords have been adopted into American English, helping keep the Yiddish culture alive. While Yiddish hasn’t been established anywhere as a national language, it has achieved worldwide status. Remarkably, Yiddish has been able to stay alive through American Jews, even though the Jewish population in the U.S. is small, and most American Jews don’t speak Yiddish. Through its lively nature, Yiddish can express nuanced feelings in concise phrases, creating an ongoing demand for Yiddish everywhere. Yiddish has been recognized as part of the ‘Official English’ language by establishing a prominent presence in current English dictionaries as well as becoming an integral part of many American dialects. Yiddish loanwords are a remarkable addition to the English lexicon, particularly to express complex concepts in simple one- or two-word slang phrases.

Works Cited

(Fishman, 1957) Fishman, David E. “The Rise of Modern Yiddish Culture.” University of Pittsburgh Press, 1957. Https://Books.google.com/Books?Hl=En&Lr=&Id=zNPacCU7GzQC&Oi=Fnd&Pg=PP1&Dq=Yiddish+Culture+America&Ots=T3TTSUxV_A&Sig=XYnoqtWLjnu34BWEvze0GzGjcRk#v=Onepage&q=Yiddish%20culture%20america&f=False

(Steinmetz, 1986) Steinmetz, Sol. “Yiddish & English: The Story of Yiddish in America.” Google Books, University of Alabama Press, 1986, https://books.google.com/books?id=B7lIDwAAQBAJ&lpg=PR7&dq=Yiddish%20dialect%20in%20america&lr&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false