John O'Loughlin: Will Russia recognize the independence of two eastern Ukraine republics? Here’s what people there think.

Those who live in the Donbas region care more about bread-and-butter issues, our latest surveys reveal.

At the heart of the current Russia-Ukraine crisis is the long-standing conflict in the Donbas region in eastern Ukraine, divided since 2014 into separate territories controlled by the Ukrainian government and by Russian-backed separatists. On Tuesday, the Russian Duma appealed to President Vladimir Putin to recognize separatist regimes there as independent states. Putin also declared that “genocide” was happening in the Donbas.

We have researched public opinion on both sides of the Donbas dividefor the past six years. Our largest research survey there, which concluded just two weeks ago, reveals a dimension of the crisis that many may overlook: economic despair. Ordinary people on both sides of the conflict line hold similar attitudes about their well-being and current conditions, despite their wartime experience or geopolitical orientation.

Ukraine’s economy has not flourished

It is now 30 years since the collapse of the Soviet Union, but Ukraine’s gross national income per capita has stagnated at roughly 80 percent of the level in 1990. Neighbors such as Poland, relatively poorer at independence than Ukraine, are now more economically prosperous, with per capita incomes that greatly exceed those of ordinary Ukrainians. Living standards in the Donbas, once an industrial powerhouse, have plunged because of the ongoing war.

We’ve tracked public opinion in the Donbas since 2016

The Donbas region today comprises Kyiv-controlled parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts (government-controlled areas), and the separatist Donetsk and Luhansk “people’s republics” (DNR/LNR). Both parts have experienced war and forced population movements within and beyond the region, and the war has cost more than 14,000 lives. The Donbas front line remains an anxious divide as Russian military forcesmass at various points on Ukraine’s eastern, southern and northern borders.

Our prior surveys on both sides of the contact line in 2016, 2019 and 2020 reveal divergent responses to questions about the preferred final status for the separatist republics. Conflict zones are difficult environments for public opinion research. Sample design, mode of surveying (telephone, online or face-to-face) and question framing all require considerable care.

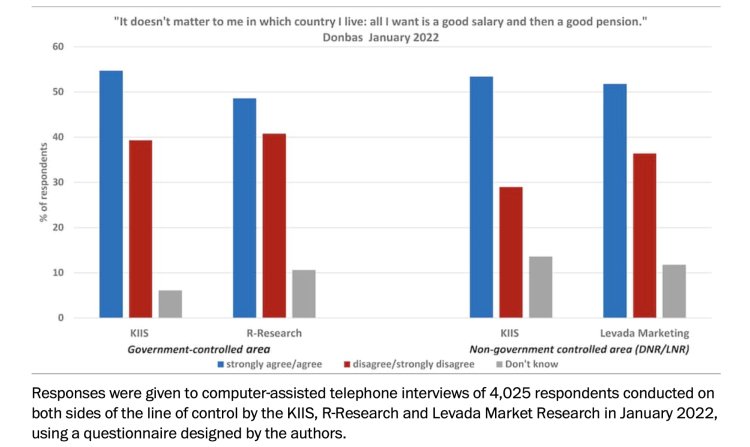

This year, we used three reputable companies — one from Ukraine, one from Russia and one based in the U.K. — to conduct a computer-assisted telephone survey of 4,025 people Jan. 14-17. Simultaneous double surveys on each side of the contact line provide an additional check on potential biases introduced by different survey companies. The Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) and U.K.-based agency R-Research each surveyed in the government-controlled areas while KIIS and Levada Market Research in Moscow surveyed in the non-government-controlled area (the Donetsk and Luhansk people’s republics).

All three companies used the same questionnaire and methodology and conducted the same number of interviews in each location, allowing us to compare the responses between the two parts of the Donbas. The survey included questions about war experiences, forced relocation, blame for the conflict, plans in case of a Russian invasion and trust in political leadership. Our respondents expressed many different views on geopolitical questions — but particularly striking were the answers to a question asking them to prioritize their economic well-being or the identity of the government in charge.

What do ordinary citizens want?

Reporters often remark that ordinary Ukrainians appear indifferent to the passions of geopolitics. In 2014, British journalist Tim Judah interviewed a 27-year-old woman in Sloviansk, in Donetsk oblast, who reported, “It does not matter if I live in Russia or Ukraine. All I want is a good salary.”

We’ve adapted this sentiment in our research surveys in Ukraine and in other parts of the former Soviet Union — as a way to gauge whether ordinary economic well-being, not the identity of the government in charge, is a primary concern. We modified the statement slightly, adding pensions along with a salary to make the survey question relevant for older respondents.

In our January Donbas surveys, half of the respondents, regardless of whether they lived in either government- or non-government-controlled areas of the Donbas, agreed that it does not matter where they live, whether in Russia or Ukraine (51.8 percent agree in the government-controlled area and 52.6 percent agree in the separatist republics).

Those who disagreed with the prompt, apparently putting politics over economic well-being, totaled 37.9 percent (16.1 percent disagree and 21.8 percent strongly disagree). Fewer than 1 percent of respondents refused to answer the question and 8 percent said they could not give an answer to this tough choice. As seen in the figure, these patterns are consistent on both sides of the contact line and also evident in the results collected by each of the various survey companies. These answers are similar to our survey in the same Donbas regions in late 2020.

How is it that citizens appear little invested in the territorial outcome of the ongoing Donbas conflict? The survey responses point to a socioeconomic answer: 11.5 percent of the overall sample reported they did not have enough money for food, and 30.2 percent indicated they could afford food but no other expenditures. Over half (54 percent) of the residents of the Donbas as a whole report that their families have been directly affected by the war, either suffering casualties or being forced to move.

While poorer residents (54 percent) and younger people (59 percent) are more likely to agree that they don’t care what country they live in as long as they have a decent salary, those most affected by the war are less likely to agree with the statement (46 percent) — suggesting they prioritize which government is in control over their family’s well-being.

It’s understandable that the current crisis diplomacy and media coverage are preoccupied with the risk of a large-scale war, resurrected talks and de-escalation options, and narratives of geopolitical spheres of influence.

This crisis, however, has a long backstory. Ukraine’s uneven economic development since its independence, especially in devastated industrial regions like the Donbas, is a crucial part of that story. Geopolitics and territorial belonging certainly matter, but economic stagnation has a powerful effect on the lives of ordinary people in conflict zones. What flag flies overhead matters less than material stability in their lives, our research suggests.

John O’Loughlin, professor of distinction at the University of Colorado at Boulder, is a political geographer with research interests in the human outcomes of climate change in sub-Saharan Africa and in the geopolitical orientations of people in post-Soviet states.

Gwendolyn Sasse, director of the Center for East European and International Studies (ZOiS), professor in the department of social sciences at Humboldt University of Berlin and senior research fellow at the University of Oxford’s Nuffield College, researches the dynamics of war, identities, protest and migration. She is currently engaged in a series of survey projects in Ukraine, Russia and Belarus.

Gerard Toal, professor in the School of Public and International Affairsat Virginia Tech’s campus in Arlington, Va., is the author of “Near Abroad: Putin, the West and the Contest for Ukraine and the Caucasus” (Oxford University Press, 2019).

Article reprinted from The Washington Post, Feb 17, 2022.