ATLAS Professor Laura Devendorf Explores Innovations in Weaving at CHI 2023

Weaving has been a central craft in global culture for thousands of years—so ubiquitous that it often feels invisible. Laura Devendorf, ATLAS Unstable Design Lab Director, Information Science faculty member, is changing this perception by proving that weaving is very much a source of radical innovation, and inspiring others in the world of computer-human interaction to expand their conception of what advanced materials can look like.

At this year’s ACM CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, in Hamburg, Germany, Devendorf presented research 5 years in the making on the intersection of human-computer interaction and textile weaving, a true melding of engineering and craft.

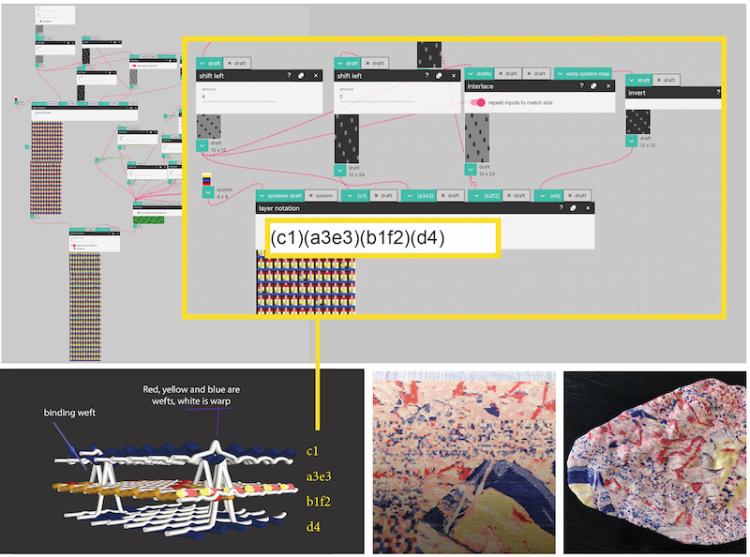

Her paper, AdaCAD: Parametric Design as a New Form of Notation for Complex Weaving (Laura Devendorf, Kathryn Walters, Marianne Fairbanks,Etta Sandry [ATLAS Unstable Design Lab weaving resident], Emma R. Goodwill [ATLAS Unstable Design Lab member, undergraduate student]) was awarded Best Paper Honorable Mention at the conference.

[video:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J7q3fc9aArM]

In addition to presenting the paper, Devendorf demoed her research, shared sample textiles and distributed workbooks to ground observers in an understanding of the craft and its potential in advanced computer-human interaction. Her open-source framework bridges communities of weavers and engineers around the common goal of pushing the boundaries of textile structure.

Weaving is not the flat plane art many think it is. It can be a medium for building precisely-designed 3D structures, interwoven shapes and generative patterns. Weavers can build these structures without adhesives from materials they can mend and reharvest.

Devendorf notes that she “has been interested in people working in textiles and seeing how that work is happening in all different spaces and from disciplinary perspectives. It feels like it’s building from many unique angles.” At CHI, she got to see how her work fits into so many disparate conversations. Indeed, one of the most exciting elements of the conference was showing tangible woven objects and proposing new ways to explore the techniques used to create them.

By opening up possibilities for how we make and interact with woven forms, Devendorf’s work has sparked dialog around the future of textiles. It is a visible technology—something you can hold in your hands—one that embodies experience, play and storytelling and encourages collaborative interaction.

For example, when we think about heirlooms, we envision objects passed through generations because they hold meaning. What if we could make that meaning literal? What if a mother could weave a blanket embedded with digital data that gives it context and a deeper narrative for her children and grandchildren? What if it could store new memories across generations? This could be possible through weaving electronic materials or even designing computer-readable woven patterns.

Devendorf takes a unique approach to thinking about her research. “We approach everything we work with as craftspeople, whether textiles, clay or software from a perspective of sculpting. Change a variable and see what happens, then follow that conversation to new design spaces.”

The future of human-computer interaction is not purely digital, it is very much embedded in craft. Devendorf’s work proves that fiber art is a medium for radical innovation.