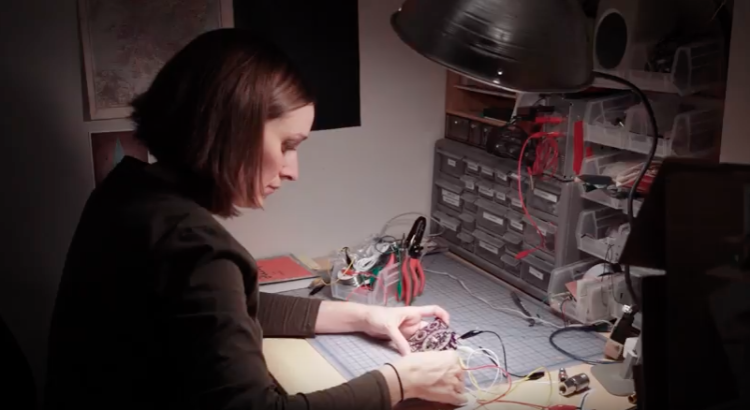

Alicia Gibb featured in Red Hat video

Alicia Gibb

Today, Alicia Gibb is an ATLAS instructor, director of the ATLAS Blow Things Up (BTU) Lab and a nationally recognized champion of the open source hardware movement, but her journey started out with a very different trajectory.

In college, she studied art education and her first job was as a librarian. It was while she was completing one of her two master’s degrees—library science and art history—that she found her calling after learning to write code and build websites.

“I just fell in love with open-source software,” says Gibb. “As librarians, we were taught that freedom of access and freedom of information is paramount to libraries and protecting it is a librarian’s duty. These same freedoms drew me to open source.”

Soon after, Gibb learned about open-source hardware (OSHW)—devices whose designs had been released to the public so that anyone could make, modify, distribute and use them—and she was similarly attracted.

This week Red Hat, a publicly-traded, multinational software company providing open-source software products, recognized Gibb's influence in the OSHW movement by releasing a documentary-style video about her. She was a keynote speaker at the Red Hat Summit in May in Boston, where she spoke to 4,000 attendees about why OSHW is crucial to innovation.

In 2010, Gibb organized the emerging OSHW conference with Ayah Bdeir, founder of littleBits, and in 2012 she formed the nonprofit, Open Source Hardware Association (OSHWA), which aims to educate and promote the use and adoption of open-source hardware. A year ago she introduced the association’s new OSHW certification program, an OSHWA product logo that protects consumers by ensuring that certified products meet a uniform and well-defined standard for open-source compliance. This week OSHWA released a certification app.

“In Europe, people have no problem understanding the concept of open source,” says Gibb, who also spoke about OSHW in Stockholm and Croatia. “It’s very much a part of their culture. In the United States, most people don’t want to share the source of what’s making them money, but when you share, you make more money.”

Gibb ticks off the reasons why OSHW is important.

Gibb directs the Blow Things Up (BTU) Lab at CU Boulder's ATLAS Institute.

Historically, engineers usually don’t receive royalties or recognition for product patents owned by their employers, she said. And companies spend millions of dollars defending their patents, such as when Apple and Samsung engaged in a $400 million patent infringement suit over the design of cell phones and tablets, with costs being passed onto consumers.

“Patents themselves are expensive,” she says. “It costs $50,000 to get a patent, and if you have 50K to start a company, you probably don’t want to use it for that.”

With OSHW, the engineering community returns the favor of free hardware design by offering free product feedback. And anyone can incorporate another person’s improvements into their products.

As the founder of Lunchbox Electronics, an education-related open-source hardware company, Gibb is practicing what she preaches. Her company makes electronic components that are compatible with Legos, and consumers are free to design new parts for the toys and sell them without worrying about patent infringement.

“This is the beauty of OSHW,” she says. “The potential for innovation and creativity is limitless.

“Patents make you lazy. You depend on lawyers, and meanwhile you stop innovating. As a consumer, you want the most innovative product on the market.”