Meet the scientist who stumbled into the cold—and stayed

Top image: Sunset over the Royal Society Range (background), sea ice in McMurdo Sound (mid-ground) and McMurdo Station from John Cassano's 2025 Antarctic trip. (Photo: John Cassano)

John Cassano, professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences at CU Boulder, lead scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center and fellow at CIRES, recently returned from his 15th research trip to Antarctica

The first time John Cassano flew to Antarctica, he found the 12-hour commercial flight from Los Angeles to Auckland, New Zealand, uncomfortable. Then he boarded a C-130 cargo plane bound for Antarctica.

“Put me on a commercial plane in a middle seat for 12 hours,” he says, chuckling. “I’ll take that over being in a cargo plane any day.”

John Cassano, a CU Boulder professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences and self-described "weather weenie," has been pursuing research in Antarctica since 1994.

That was January 1994. Cassano was 25 and a graduate student who had agreed to work on a project installing weather stations in Greenland and Antarctica. He figured he’d go once, check Antarctica off his list and move on with life. Thirty years later, he’s still going back.

Cassano did not plan to be a polar researcher. Growing up in New York, he imagined a career in architecture—something tangible, predictable. But a freshman weather class at Montana State University changed everything. “I decided architecture wasn’t for me.”

Meteorology seemed a better fit. Montana State didn’t offer meteorology, so Cassano earned an earth science degree and headed to graduate school at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, intending to study storms. Then came an invitation from Charles Stearns, professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, asking if Cassano would be interested in working on a project in Antarctica.

“I had no real interest in the polar regions,” Cassano admits. “But I wasn’t going to pass up the chance to go to Antarctica once.”

That “once” became a career. After two field seasons with Stearns, Cassano pursued a PhD at the University of Wyoming, focusing on Antarctic meteorology. Today, as a professor in the University of Colorado Boulder’s Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, he has lived about a year in Antarctica over the course of 15 trips there.

Cassano is also lead scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center and a fellow at CU Boulder’s Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences.

'A weather weenie at heart'

The science keeps him coming back. Cassano’s work explores how the atmosphere behaves in Earth’s most extreme environments—knowledge that underpins climate models and weather forecasts worldwide.

The adventure is also alluring. “I’m a weather weenie at heart,” he says. “I like experiencing extremes—strong winds, big snowstorms, really cold temperatures. Antarctica gives me that.”

He recalls standing in minus 56°F air, frostbite nipping his fingers as he launched drones. “I enjoy experiencing those conditions,” he says. “I wouldn’t want to camp in a tent for months like the early explorers, but I like the challenge.”

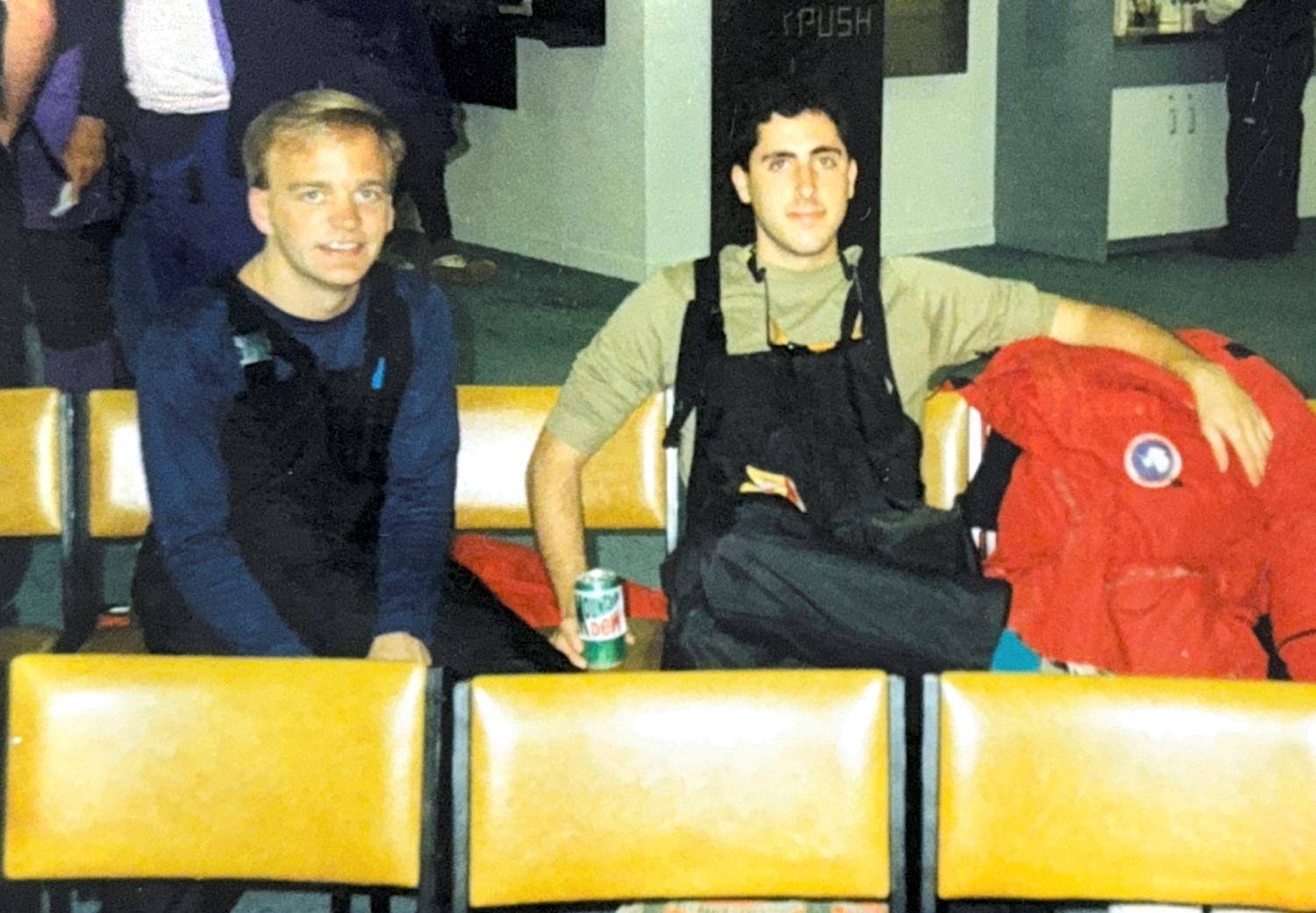

John Cassano (right) and then-fellow graduate student Mark Seefeldt (left), now a research scientist in Cassano's group at CIRES, on their first trip to Antarctica in 1994. (Photo: John Cassano)

Cassano’s contributions have helped reshape polar science. In 2009, he led the first U.S.-funded drone research campaign in Antarctica, opening new ways to measure the atmosphere where traditional instruments fall short.

“Drones let us probe the boundary layer—the part of the atmosphere that exchanges heat and moisture with the surface,” he explains. “That’s critical for understanding climate.”

Earlier, as a postdoctoral researcher at Ohio State University, Cassano helped modernize Antarctic weather forecasting. The Antarctic Mesoscale Prediction System, launched in 2001, transformed flight safety.

“When I started going down in the ’90s, forecasters were confident about eight hours out,” he says. “Now it’s five days. That’s huge.”

That’s a big change for several reasons, not the least of which is that an eight-hour forecast could change from the time a plane left Christchurch, New Zealand, and got closer to Antarctica. Planes often had to turn around mid-flight back then, Cassano recalls.

Witnessing dramatic changes

Cassano has witnessed dramatic changes in three decades of research.

Arctic sea ice has declined about 40 percent in recent decades. Antarctic sea ice, once at record highs, now hovers at record lows. Ice shelves are collapsing.

“These changes matter,” he says. “They alter the temperature gradient between the tropics and poles, which drives global weather. Even if you never go to the polar regions, it affects the storms you experience.”

Meanwhile, fieldwork isn’t all adventure. “Emotionally, it’s hard,” Cassano says. “When I was single, I didn’t mind being gone for months. Now, being away from my wife and daughter is tough.”

Comforts are few: shared dorm rooms, institutional food and the knowledge that if something happens at home, he can’t leave. “Once you’re there in August, you’re stuck until October.”

But Cassano treasures the Antarctic community—a self-selecting group of scientists and support staff who thrive in isolation. “You don’t wind up in Antarctica by mistake,” he says.

“Everyone wants to be there. Contractors work six-month stints and spend the rest of the year traveling. It’s like living in a travelogue.”

Kara Hartig (left), CIRES visiting fellow postdoc, and John Cassano (right), in Antarctica during the 2025 research season. (Photo: John Cassano)

He loves the stories: a mechanic who spent his off-season trekking through South America, a cook who had just returned from hiking in Nepal. “You hear all these amazing experiences,” Cassano says. “It’s like living inside a travel magazine.”

Behind every scientific breakthrough lies a vast support system. “I can focus on science because others make sure I have food, water, transportation and a warm place to sleep,” Cassano says. “That infrastructure is critical.”

Cassano worries about the cost of fieldwork and the ripple effects of recent disruptions. “Field projects are expensive,” he says. “COVID and a major McMurdo Station rebuild created a backlog. My project was supposed to be in the field in 2021—we went in 2025. NSF is still catching up.”

Federal priorities are a concern in the current political climate, but Cassano suggests that Antarctic research might be less vulnerable than other kinds of federally sponsored science.

“Antarctic research has always had a geopolitical dimension,” Cassano notes. “The Antarctic Treaty encourages nations to maintain scientific programs. It’s how you keep a seat at the table.”

Constant curiosity

For Cassano, mentoring is particularly rewarding. “I love bringing new people down,” he says. “Seeing Antarctica through their eyes makes me excited again.” On his latest trip, he watched a young researcher, Kara Hartig, CIRES visiting fellow postdoc, as she experienced the ice for the first time. “Her enthusiasm reminded me why I do this.”

That excitement ripples outward. After Cassano shared photos in class, a former student emailed, saying, “I’m on my way to Antarctica to work as a chef at McMurdo,” the largest research station on the continent.

“He just wanted to experience it,” Cassano says. “I think that’s awesome.”

Cassano’s curiosity remains undiminished. On his latest trip, when drones failed to arrive, he improvised with van-mounted sensors, uncovering puzzling temperature swings across the ice shelf.

What might we learn from the data? “It hints at important processes,” he says. “Now we need to go back and figure out why.”

After three decades, Cassano still marvels at the complexity of the atmosphere—and the urgency of understanding it. “Increasing our knowledge is broadly beneficial,” he says. “And for me, it’s just fascinating.”

Did you enjoy this article? Subscribe to our newsletter. Passionate about atmospheric and oceanic sciences? Show your support.