One-hit wondering: Who let the dogs out?

The Baha Men hit, released 25 years ago, occupies a distinctive spot in music and sports history, along with “Macarena” and other novelty earworms

A quarter century ago, the world was gripped by a deeply philosophical question: “Who let the dogs out?” Twenty-five years after the Baha Men hit became a cultural phenomenon, the history of the song reveals the evolution of a viral novelty song while reflecting a music industry at a transition point at the start of the millennium.

Listeners likely are most familiar with the Baha Men cover of the song that was released on July 26, 2000, but the song, and its famous hook, has a much longer history. Ben Sisto’s 2019 documentary “Who Let the Dogs Out,” traces the history of the hook, or chant, back to the 1980s, when high school teams like the Dowagiac Chieftains in Michigan and Austin Reagan Raiders in Texas would exclaim “Ooh” or “Who let the dogs out,” woofing along with the chant.

Jared Bahir Browsh is the Critical Sports Studies program director in the CU Boulder Department of Ethnic Studies.

Several other songs with a similar hook were released in the 1990s, leading to years of lawsuits over the rights to the song. Lawsuits targeted Anslem Douglas, who is credited with writing the Baha Men version of the song—which is a cover of his song “Doggie,” written as a feminist response to men catcalling women. In 1999, rapper Chuck Smooth recorded a song titled “Who Let the Dogs Out?” sampling the infamous hook and later joining the lawsuit.

Before the Baha Men recorded their version, infamous producer Jonathan King, who had several hits in the United Kingdom and helped discover Genesis, recorded his own cover of “Doggie” under the name Fat Jakk and his Pack of Pets. King brought the recording to Steve Greenberg, who is credited with discovering Hanson, the Jonas Brothers, Joss Stone and AJR. Greenberg convinced the Baha Men, whom he discovered in 1991 and signed to Atlantic Records subsidiary Big Beat, to record a cover of the song. The Baha Men hesitated because the song was already popular in the Caribbean, but Greenberg convinced them, creating the label S-Curve Records to produce the album.

Even before the Baha Men version was released, teams like the Mississippi State University Bulldogs played the Chuck Smooth recording of the song beginning in the fall of 1998, and soon other teams followed. In June 2000, and as a joke, Seattle Mariners Promotions Director Gregg Greene used the Baha Men recording as a walk-up song for backup catcher Joe Oliver, several weeks before the song was released. All-Star shortstop Alex Rodriguez then requested the song; other teams adopted the song as an anthem. The New York Mets claim they used the song first, leading to both the Mariners and Mets exchanging jabs over who popularized the song as each team made runs deep into the playoffs.

As “Who Let the Dogs Out” made its rounds in stadiums and arenas in the United States, it became a global hit, reaching number one in several countries, including Australia. The song only peaked at No. 40 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in the United States, barely qualifying the song as a one-hit wonder. However, like other novelty songs—including Aqua’s “Barbie Girl”—its cultural impact goes far beyond its performance on the chart

The song got another boost when it was included on the “Rugrats in Paris—The Movie” soundtrack, which was released two weeks after the song peaked on the Billboard Chart, ensuring children would continue “woofing” along with the song well into the next year. The song’s charm did wane in 2001, especially as sports fans began to find the song more annoying than energizing. But it still represents a unique time in music and a shift in stadium music in sports.

From Napster to TikTok

The late 1990s saw huge changes in technology that caused significant disruptions in the music industry. Throughout the 20th century, music technology continually advanced, making music more portable and providing more avenues to cater musical tastes to individual listeners.

The 1950s provided a foundation for modern popular music, as young listeners became the target of music producers and disc jockeys—especially as other forms of programming, like scripted programs and variety shows, transitioned from radio to television. Radio stations focused more on broadcasting music, especially as rock ’n’ roll exploded in popularity thanks to DJs like Alan Freed, who helped popularize the term in 1951. Rock ’n’ roll’s growth was supported by improvement in audio technology like the electric guitar, condenser microphones and enhanced amplifiers.

Radio put a greater focus on individual hit songs or singles, separating popular songs from a larger album. Album sales in all formats remained popular through the 1990s, but the greater focus on hits shifted the audience’s listening habits, especially as DJs curated shows of hit songs from a variety of artists. The introduction of the 7-inch 45 rpm record in 1949, which ran for between 5 to 6 minutes, also promoted single sales and became standard in jukeboxes.

The popularity of rock ’n’ roll among young listeners raised criticism from parents and politicians over concerns of sexualization and the influence of Black artists promoting integration. However, by the mid-1950s, teenagers found more freedom as the transistor radio came to market in 1954, allowing radios to travel outside of the home and car. FM radio, with its higher-quality sound, also slowly spread as the FCC implemented a rule in 1964 forcing FM stations in cities to create original programming rather than simply simulcast from AM; many FM stations chose music formats.

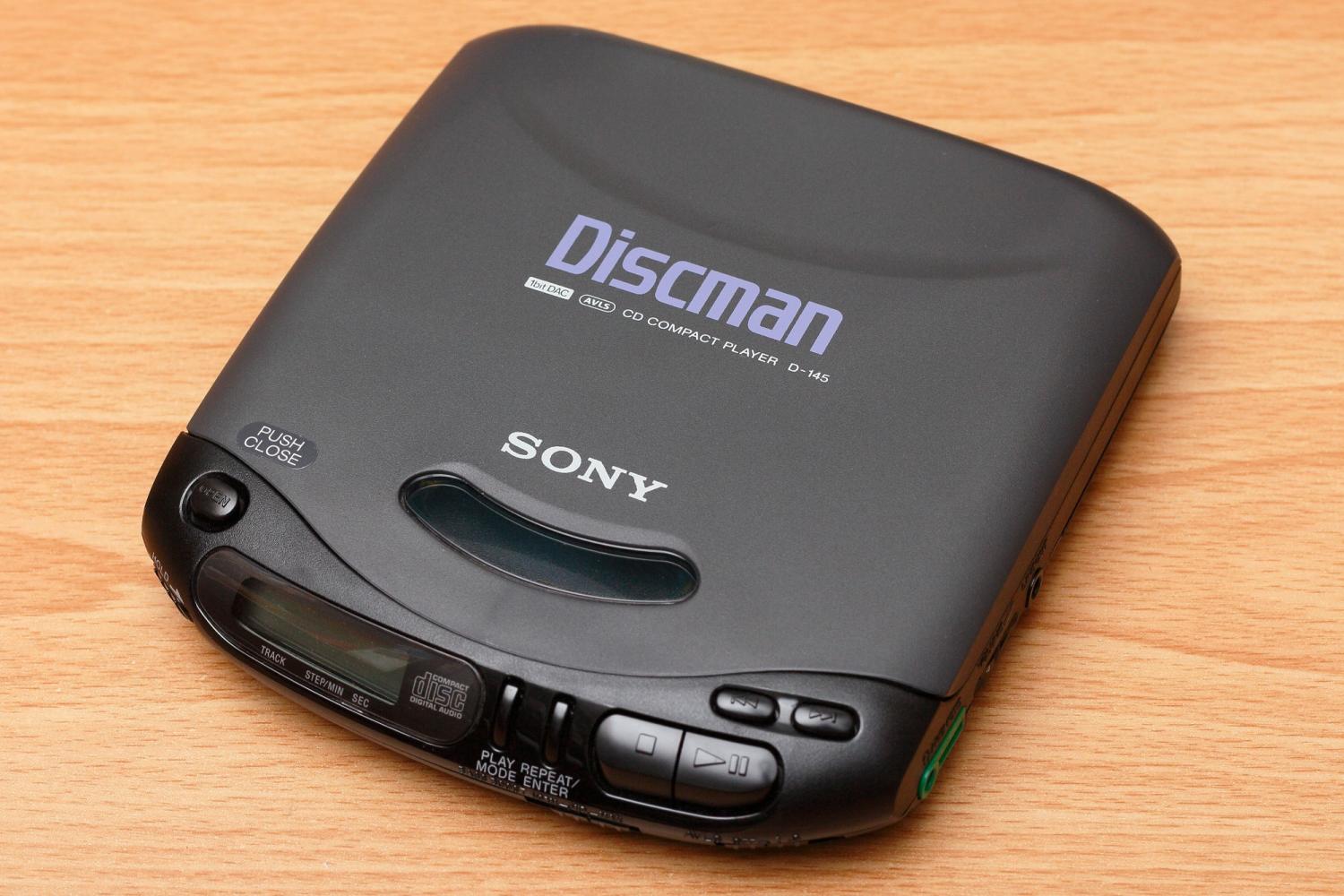

Music continued to become more portable and individualized as magnetic tape formats, including the 8-track and then the compact cassette, offered the option to listen to singles and albums on the move. They also allowed listeners to curate their own music. Through the 1970s, 8-tracks dominated the music market, peaking in 1978 as the preferred tape format for cars and homes. In 1979, Sony introduced the Walkman, which worked with compact cassettes that were not only more portable but also allowed listeners to fast forward and rewind to listen—and relisten—to their favorite songs anywhere.

Following decades of work by scientists to develop digital audio, the compact disc introduced the format to the public in 1982, allowing for greater portability, track selection and higher-quality sound. It later allowed users to upload or “rip” music to computers, helping to expand music sharing through peer-to-peer (P2P) networks. Although P2P promoted the sharing of all types of files, Napster’s launch in 1999 and LimeWire’s in 2000 popularized the practice of downloading compressed music files as MP3s.

In spite of lawsuits brought by artists like Metallica and Dr. Dre over copyright concerns and the music industry becoming anxious over how MP3s would impact sales and revenues, Apple introduced the iPod in October 2001. It was not the first portable digital music player, but it drastically improved data capacity, battery life, functionality, the file transfer process and portability.

In 1979, Sony introduced the Walkman, which worked with compact cassettes that were not only more portable but also allowed listeners to fast forward and rewind to listen—and relisten—to their favorite songs anywhere.

Users continued to download music through file-sharing sites even as Napster fought lawsuits before shutting down in July 2001. iTunes launched eight months before the iPod debuted, allowing for computer music management, including the ability to more easily rip CDs and build both mix CDs and playlists for the iPod when it launched. The iTunes store launched in 2003, allowing for seamless purchase of songs and albums, which could be transferred easily to the iPod. However, music sharing remained popular.

The digital era increased the focus on singles over albums, as consumers have increased options to curate their playlists by selecting individual songs rather than full albums through subscription-based streaming services like Spotify and YouTube Music. A few top artists like Taylor Swift and Beyoncé have strong fanbases that may buy full albums, but their albums sales still pale in comparison to artists of the 20th century.

One-hit wonders, novelty songs and ear worms

There is no official definition of a one-hit wonder, but in his book One-Hit Wonders, music journalist Wayne Jancik defined it as "an act that has won a position on Billboard's national, pop, Top 40 just once.” The Baha Men barely meet these requirements in the United States, and because of its rise as a stadium anthem and its gimmicky hook, some see “Who Let the Dogs Out” as a novelty song. A song is considered a novelty if there is some foundation of humor or unusual hook or sounds within the song.

Throughout modern music history, there have been countless songs that can be considered novelty—with artists like The Coasters (“Yakety Yak”) and “Weird Al” Yankovic enjoying successful careers from their novelty and parody songs. Cartoon bands like Alvin and the Chipmunks, created by Ross Bagdasarian (stage name David Seville) and The Archies (“Sugar, Sugar”) are considered novelty acts despite their music hitting No. 1 on the Billboard charts. Many kids’ (or children’s) songs are considered novelty songs when they chart, including “The Ballad of Davy Crockett” from the Disneyland miniseries in 1954 and, more recently, “Baby Shark.”

Like “Who Let the Dogs Out,” another novelty song, “Macarena,” was a minor hit for other artists before catching on when it was re-recorded and reintroduced to the U.S. market in the summer of 1995. Considering listeners rarely know the lyrics of these songs beyond the catchy hook, the much-repeated eponymous lyrics could also be considered an earworm.

An earworm is a memorable piece of music that occupies someone’s mind well after the song stops playing. Earworms are often associated with advertising jingles like McDonald's "I'm Lovin' It" or Oscar Mayer's "Oscar Mayer Weiner Song," but music listeners can also develop ear worms from catchy songs—especially if the hooks are replayed and the tune is associated with particular memories like sporting events. Another example of this is Steam’s “Na Na Hey Hey Kiss Him Goodbye.”

Social media has placed an increased emphasis on hooks, creating ear worms that can promote a song to hit status or revitalize a song's popularity. A recent example of both of these phenomena is Doechii’s “Anxiety,” which she originally recorded in 2019. After the hook went viral on TikTok, she recorded the song again in 2025, leading to its becoming a top-ten single.

“Who Let the Dogs Out” and “Macarena” unknowingly represent a shift in the music industry at the turn of the 20th century. These pre-social media viral songs, popularized by a novel hook and gaining popularity off-radio, can be considered ahead of their time—with the “Macarena” even fostering a viral dance. Although playing these songs may result in more eye-rolls than cheers, their path to success cannot be overlooked in this modern digital music era.

Jared Bahir Browsh is an assistant teaching professor of critical sports studies in the CU Boulder Department of Ethnic Studies.

Did you enjoy this article? Subscribe to our newsletter. Passionate about critical sports studies? Show your support.