Breaking the color barrier in baseball leadership

Frank Robinson at Nationals Park. (Photo: Nick Wass/Associated Press)

Fifty years after Frank Robinson became the first Black manager in Major League Baseball, the league is struggling with a significant decline in Black players and leaders

As Black History Month begins Feb. 1 and Major League Baseball celebrates the 50th anniversary of Frank Robinson making his debut as the first Black manager, the sport is at a point of introspection with the lowest number of African Americans players in Major League Baseball since the 1950s.

The milestone is both a reminder of how far baseball came since segregation and how delicate inclusion efforts are in baseball and other institutions in the United States.

Jared Bahir Browsh is the Critical Sports Studies program director in the CU Boulder Department of Ethnic Studies.

As the United States emerged from World War II, Plessy v. Ferguson and Jim Crow laws continued to keep the country largely segregated. The war, however, was also a turning point for African Americans, who demonstrated that their service was of equal value to others who fought in the war.

One such soldier was Jackie Robinson, the first athlete to letter in four sports at UCLA. His teammates Kenny Washington and Woody Strode broke the color barrier in the NFL in 1946, while he did the same in baseball the following year—seven years before Brown v. Board of Education determined that “separate but equal” thresholds for segregation were unconstitutional. Jackie Robinson’s last season as a player was 1956, the same season a young Frank Robinson debuted with the Cincinnati Reds.

In 1972, the Reds played the Oakland Athletics in the World Series. By that point, Frank Robinson had been traded twice and spent the season playing for Jackie Robinson’s former team, the Dodgers.

During Game 2 of the series in Cincinnati, Jackie Robinson was honored 25 years after breaking the color barrier in baseball. During his speech accepting the honor, he appealed to MLB leaders to hire the first Black manager, an opportunity he never got despite his expressed desire to manage a team. Jackie Robinson died nine days after his speech—Oct. 24, 1972—never seeing Frank Robinson hired as the first Black player-manager two years later.

Robinson was traded to Cleveland during the 1974 season after openly campaigning for the manager position with the Dodgers. Cleveland was the first American League team to sign a Black player in 1947, Larry Roby, and broke ground again 28 years later by hiring Robinson. He was the first player to win MVP in both the National and American League, but had a rocky tenure with the team, often being pushed to play when he wanted to focus on managing and butting heads with the star player, Gaylord Perry. He did lead the team to its first winning record in eight years in 1976, the last season he played, before being fired during the following season.

Inclusive Sports Summit

We change the game: Embracing the value of inclusive sports and recreation

When: 9 a.m.-6:30 p.m. Wednesday, Feb. 5

Where:Dal Ward Athletic Center and Main Student Recreation Center

During this summit participants will

- Identify challenges, opportunities and best practices for advancing diversity, equity and inclusion work as practitioners and supporters.

- Learn tangible takeaways to build bridges and build unity across similarities and differences.

- Build skills and practice techniques for addressing inequities to help increase student retention, engagement and success.

- Connect with departments and programs across campus that are available to support students, staff and faculty.

The Inclusive Sports Summit is free and open to faculty, staff, students and community members.

Robinson went on to manage the San Francisco Giants and his former team, the Baltimore Orioles, winning manager of the year in 1989. He was fired from the Orioles during the 1991 season—the year Major League Baseball had the highest percentage of African American players in the league, 18% of all players. The following season, Cito Gaston became the first African American manager to win a World Series.

Robinson continued to work in the league office after his time with the Orioles, returning to the dugout after being tapped by MLB to manage the Montreal Expos, which the league owned at the time. The team moved to Washington D.C. in 2005 and his final season as manager was the first season for the newly founded Washington Nationals.

Declining youth participation

The dearth of opportunities for African Americans to coach and assume leadership positions in sports is not new; however, baseball has seen the most precipitous drop in participation, down to 6% during the 2024 season.

Contributing to this drop is the lack of African Americans in leadership positions, with only two African American managers, Ron Washington (Angels) and Dave Roberts (Dodgers), and one general manager, Dana Brown (Astros). In spite of these paltry numbers, three of the last five World Series winners have been led by African American managers.

The numbers are even worse in college baseball, with only 5% of players and 3% of managers in Division I identifying as African American in 2024; of these 26 managers, 17 were from historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). The lack of visible leadership affects scouting, mentorship and even participation when players cannot see a career in the sport they love if they do not make it to the major leagues.

The low numbers of African American athletes in the college pipeline to the major leagues is only one of the reasons for the continued decline of African Americans in professional baseball. Like many sports, the privatization of youth sports is forcing many lower- and even middle-income families to reconsider their children’s participation in baseball. Local governments and schools have slashed recreation and athletic budgets, leading to more expensive sports like baseball to be cut, which in turn leads to a higher reliance on private leagues.

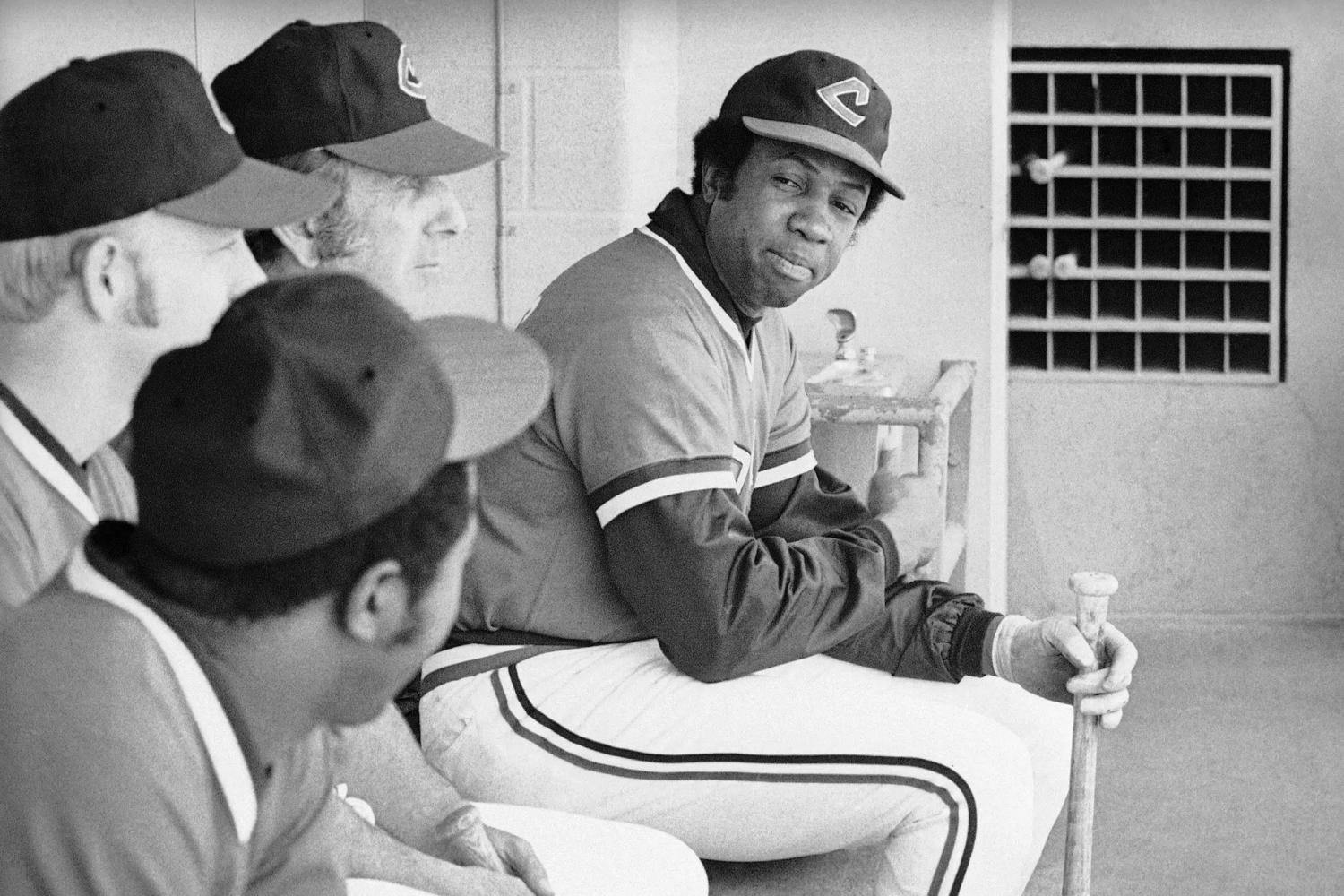

In 1975, Frank Robinson became Major League Baseball's first Black manager, assuming the role with the Cleveland Indians. (Photo: Jeff Robbins/Associated Press)

Many families ultimately balk at the cost of playing baseball, steering their children into more accessible sports as youth and high school baseball is increasingly privatized. The relatively low number of Division I baseball scholarships (11.7 maximum per team) and programs (300) compared to basketball (13 maximum scholarships across 352 schools) and especially football with 133 teams at the Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) level, 128 teams at the Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) level and with 85 maximum scholarships per team in FBS and 63 per team maximum in FCS. This also leads some families to encourage their children to focus on other sports to earn a college scholarship.

Even if amateur baseball players get drafted and signed, minor league salaries are so low that the same issues can arise that exist in youth baseball: players who cannot afford to remain in the sport. Minimum salaries are between just under $20,000 and $40,000 depending on the level, which is a significant increase from 2022, when minor league players unionized and negotiated a raise from a minimum salary between $4,800 and $17,500.

Salary expectations have led many scouts to focus on international players, particularly from Latin America, where teams will make verbal agreements with children as young as 12 in spite of the fact that teams technically cannot sign players until they are 16. MLB turns a blind eye to these agreements that often push children as young as 10 from countries like the Dominican Republic to leave school to pursue baseball. These players may be given performance-enhancing drugs to make them look more mature and artificially improve their athleticism. These players are ripe for exploitation, including lower salaries since they are beholden to Major League clubs with which they make these “handshake” deals—while their families take out loans based on future earnings, which may never appear.

Hope for long-term results

Economics and leadership are not the only factors in the decline of African Americans in professional baseball. The sport has declined as “America’s pastime” for decades, and for many is considered less “cool” than sports due to its slower pace—as well as kids’ alternative activities in the summer months—leading to a drop in viewership, especially among young viewers.

African Americans have also been historically discouraged from playing certain positions, particularly the on-field leadership positions of catcher and pitcher, the latter of which is the most visible position in the sport. This position “stacking” has historically impacted all sports, including basketball (point guard) and football (quarterback) due to discriminatory and false assumptions that African American players were not intelligent enough to play those positions. Basketball and football have seen dramatic shifts at these positions while baseball still sees limitations for African Americans at certain positions.

As with viewership, some of the issues pushing African Americans from baseball are emblematic of the decline in baseball’s overall popularity. However, there are some glimmers of hope for the future of African Americans in the sport. The House v. NCAA settlement will allow schools to increase the number of student athlete scholarships up to the roster limit, which is 34 in Division I—nearly triple the current limit.

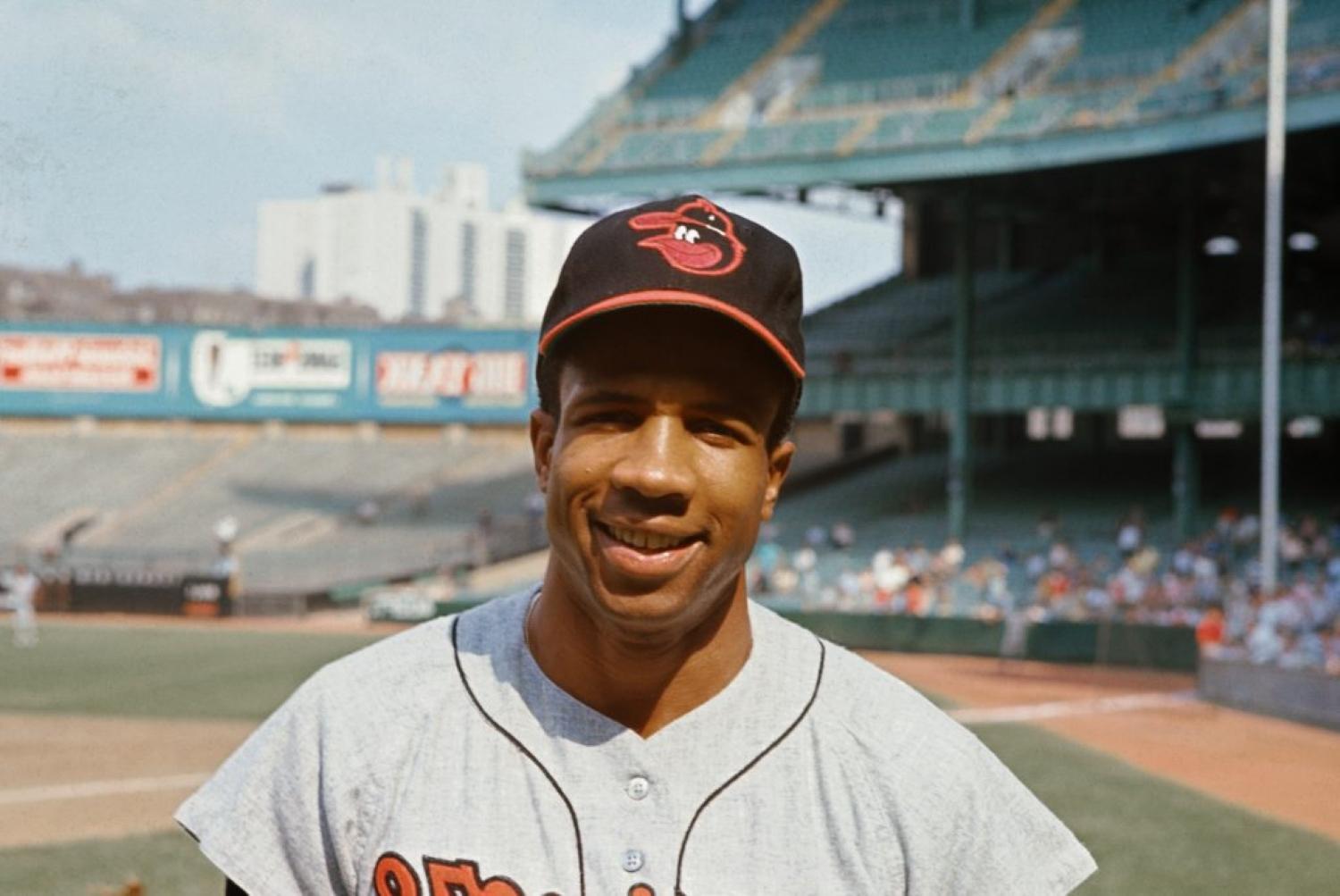

Frank Robinson had a distinguished career as a player before becoming a manager. (Photo: Bettmann Archives/Getty Images)

The opportunity to earn compensation directly from schools may also support continued involvement in the sport. Much like name, image and likeness opportunities, however, revenue sharing will disproportionately go to the top-earning sports: reports from school point to about 75% of revenue sharing going to football and 15% going to basketball with other sports sharing the rest.

Outside of the college ranks, MLB has been actively involved in a number of initiatives to try to increase participation among young players, including Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities (RBI) that was started in 1989 and is now sponsored by Nike. Players like Jimmy Rollins and recent Hall of Fame inductee C.C. Sabathia are both alumni of the program, but results have been less impactful in recent years with fewer alumni from the United States advancing to professional baseball. MLB also runs the Dream Series in Arizona, a training academy focused on African American pitchers and catchers, in conjunction with USA Baseball during the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday. The Andre Dawson Classic, named for the Hall of Fame player, is a round-robin tournament for HBCU baseball programs that runs every year at the Jackie Robinson Training Complex in Florida.

There is hope these efforts will yield long-term results and reverse the decline of African American players in baseball. The sport still needs to address its diminishing cachet among young sports fans in the United States and the lack of African American mentors and leaders in the sport, but some of the structures are there to encourage a renaissance of great Black baseball figures 50 years after Frank Robinson broke the managerial glass ceiling.

Jared Bahir Browsh is an assistant teaching professor of critical sports studies in the CU Boulder Department of Ethnic Studies.

Did you enjoy this article? Subscribe to our newsletter. Passionate about critical sports studies? Show your support.