A guy, a gun and a dangerous blonde … and why we like them

Remembering writer Raymond Chandler at the 65th anniversary of his death, a CU Boulder English scholar reflects on the hard-boiled investigator and why this character still appeals

Philip Marlowe was in a grubby waterfront hotel room “with a hard bed and a mattress slightly thicker than the cotton blanket that covered it.”

A neon light outside the window illuminated the room in red. He got up to splash cold water on his face, feeling “a little better, but very little. I needed a drink, I needed a lot of life insurance, I needed a vacation, I needed a home in the country. What I had was a coat, a hat and a gun. I put them on and went out of the room.”

Call him hard-boiled or hard-bitten, call him jaded, call him a relic—he’s all those things, and one of the most alluring and enduring archetypes in fiction. As written by Raymond Chandler, who died 65 years ago this week and who is increasingly recognized for the artistry of his writing, Philip Marlowe is the private investigator who’s seen it all and is surprised by little. He drinks too much, smokes too much, cracks wise, cracks the case and is, above all things, alone.

Mary Klages, a CU Boulder associate professor of English, notes that part of the appeal of the hard-boiled investigator character is he's a "knight in soiled armor."

Many consider Marlowe the patron not-saint of all the hard-boiled and hard-edged private investigators who followed, the semi-heroes of literature and film who solve crime, yes, but generally by immersing themselves in the sordid world of it—at the expense of relationships, health, happiness and sometimes the law.

What is the continued appeal of the hard-boiled investigator character, who’s brilliant and kind of a jerk, handy in a fight and charming when it’s convenient, all kinds of trouble—or troubled—and the ultimate cipher?

“What Marlowe and other characters like him bring in is being more of the people,” says Mary Klages, an associate professor of English who teaches a course called Crime, Policing and Detection. “(Marlowe) doesn’t have a partner, never has anybody he works with, doesn’t need a Watson figure to explain how the great brain works. He’s just a guy, and he’s not apart from the dirty world that he has to investigate. He doesn’t have this sensibility of, ‘Oh, bad guys and criminals, they’re over there and I’m something different’ that you get with other detectives or investigators.”

A desire for story

Understanding the appeal of the jaded investigator whose native habitat seems to be dark and rainy city streets begins with understanding the basic human desire for story, Klages says.

“Human beings love narratives, we love telling stories, and with mysteries there’s that added element of, ‘Can I figure out who the villain is?’ Then we get the reward of a sense of justice—somebody out there is fighting crime and that makes us feel a little bit better about living in a dangerous real world. As a reader, I can go to mystery novel and say, ‘Oh, if only there were a Sherlock Holmes or a V.I. Warshawski in the real world solving crimes and making us safer.’

“Also, stories—especially mysteries—give us all that in nice container. Anything can happen, but it’s not going to happen. Reading words on a page lets us empathize with characters and have a vicarious experience that we don’t want to have happen in real life. We experience it in a way that makes it vivid, and that has shape and that wraps up in the end with a nice, neat bow. That’s the convention in most mystery stories.”

And while there are as many types of mystery solvers in fiction as there are audiences for them—from elderly knitting enthusiasts and roadster-driving teens to insufferable British geniuses with superhuman powers of observation—the hard-boiled private eye character brought a new and interesting layer to the mystery genre.

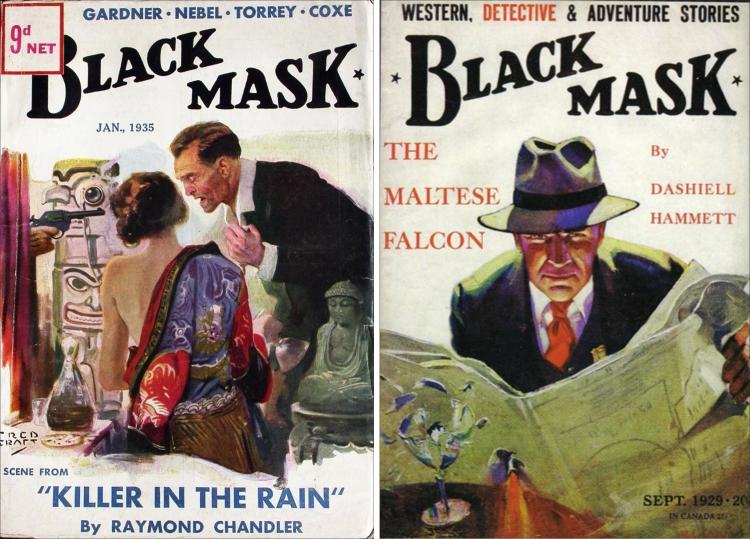

Both Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett honed the literary hard-boiled investigator writing for Black Mask magazine.

A knight in soiled armor

The character really came into his own—and in the beginning, it was always a “he”—when the pulp magazine Black Mask was launched in April 1920 by H.L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan. One of the first iterations of the hard-boiled investigator slouched through its pages in December 1922, embodied in Carroll John Daly’s novella “The False Burton Combs.”

The titular false Burton Combs memorably introduces himself in the story's fourth paragraph: “I ain’t a crook; just a gentleman adventurer and make my living working against the law breakers. Not that work with the police—no, not me. I’m no knight errant either. It just came to me that the simplest people in the world are crooks.”

His progeny includes Philip Marlowe and Sam Spade, Mike Hammer, V.I. Warshawski, Harry Hole, the Continental Op, Kurt Wallander and further generations of fictional investigators who often exist as shadow opposites to the upstanding police detectives, the crime-solving priests, the kooky Southern bookstore owners who happen upon murder, the otherwise decent people in whom readers like to think they see themselves.

Both Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, who wrote hard-boiled investigator Sam Spade, published in Black Mask and brought dimension to an essentially unknowable—and sometimes unlikable—but always compelling archetype.

“In Philip Marlowe, Chandler gives us guy who’s educated, who’s been to college, who quotes Shakespeare, but works with lowlifes,” Klages explains. “He gives us a portrait of a very dirty underworld where you can’t trust anybody, the police are corrupt, rich people are corrupt, and he looks for a kind of moral compass to guide him. I think of Marlowe as a knight in soiled armor, and Chandler makes that image at the very beginning of ‘The Big Sleep.’ He has Marlowe go into the house of a very rich client and he’s looking at this stained-glass window that shows a knight trying to free a woman from being chained up around a tree. Marlowe says something like, ‘I wanted to go up and help the guy, but then I realized he was never going to get that woman free.’

“Marlowe’s attitude is, ‘I know there’s supposed to be nobility and self-sacrifice in world, but I don’t see them, and I don’t’ believe in them. But I still want there to be some kind of morality, some kind of code,’ so he makes his own. He doesn’t follow anything traditional, he’s not religious, not spiritual, not a law and order and justice guy, so he makes his own code, and that’s part of the ongoing appeal of this character, this knight in soiled armor.”

Humphrey Bogart (left) starred as Philip Marlowe in "The Big Sleep" with Lauren Bacall. (Photo: National Motion Picture Council)

Trench coats for a modern audience

Philip Marlowe was notably embodied on film by Humphrey Bogart, as was Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade, and he’s the image many people bring to mind when they think of the hard-boiled investigator, Klages says—trench coat, cigarette and, by today’s standards, appalling attitudes toward women.

In fact, some might claim that the hard-bitten investigator is a relic of the past, but Klages argues that this character and what he (and not as often, she) represents and embodies remains relevant for modern audiences.

“It’s this idea of, ‘Why should we believe in anything when we’ve had time after time the proof that the politicians are corrupt, the police are corrupt, it’s all over the place,’” Klages says. “I think the question is, from a hard-boiled perspective, why would anybody give a damn about anybody else? You have to be in it for yourself, and I think the genius of Chandler’s portrait of Marlowe is that you have to be in it for yourself, yes, but it has to be something bigger that you stand for rather than just your own selfishness and your own greed and desires.”

She notes that Marlowe sees the world with very clear eyes, without delusion or traditional notions of hope, yet he still crafts his own kind of hope and his own code of morality, which resonates with readers and viewers today.

“I just watched first season of ‘True Detective’ and that’s a perfect example,” Klages says. “You’ve got two guys with torn up, terrible lives and part of the plot is, let’s find out how these guys with messed up lives can pursue justice. How do you take somebody who is flawed as a character and make them be the vehicle for something as elevated as truth, justice and the American way? As people who love stories, we like that complication.”

Top image: Humphrey Bogart (center) as Philip Marlowe in "The Big Sleep." (Photo: Warner Bros.)

Did you enjoy this article? Subscribe to our newsletter. Passionate about English? Show your support.