Engraving and Performing George Lynn’s Works for Viola and Piano

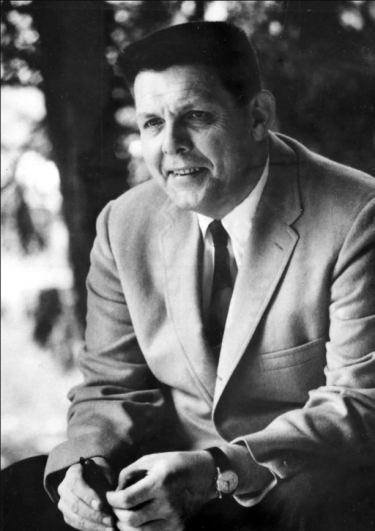

A renowned American composer, choral conductor, organist, and educator, George Lynn (1915-1989) is perhaps best known for his prolific compositional output of over 1,600 musical works. While many of his compositions remain unpublished (for example, out of his approximately 800 choral works, less than 300 are published), his entire body of work, including numerous manuscript scores, can be found in the open access George Lynn Collection at the American Music Research Center in the University of Colorado Boulder Libraries Rare and Distinctive Collections. Upon his death, Lynn’s wife, Lucille, donated his compositions to the AMRC, ensuring they would be accessible to the public. Additionally, the Lynn family sponsored a memorial scholarship to promote the continued exploration and performance of George Lynn’s music.

It is my honor as the 2022-2023 George Lynn Memorial Award Recipient to continue this explorative tradition. As a violist, I am constantly on the lookout for interesting new repertoire, and so when, in the spring of 2022, I was introduced to the George Lynn’s collection, my curiosity was piqued. The collection boasts 15 pieces for string quartet, 43 for violin, and 5 for cello, but only two for viola. Eager to see these two manuscripts for myself, I journeyed to the sub-basement of the Norlin Library and discovered that both pieces, Conversare fra Viola ed Piano and Pleasantry for Viola and Piano, were handwritten, relatively short, and unpublished. As such, I decided to submit a proposal to create performance editions, perform, and record both pieces and was fortunate enough to have my proposal accepted.

The first task on my to-do list for this project was engraving both pieces. While neat enough to distinguish the notes, dynamics, and musical markings, the handwritten scores for Conversare and Pleasantry would have been difficult to read from in live performance. The cursive musical instruction at the opening of Conversare, spensierato (meaning carefree or light-hearted in Italian), in particular took a fair amount of squinting to distinguish.

I endeavored to make my performance editions as faithful to Lynn’s scores as possible with two exceptions. First, I opted to exchange Lynn’s unconventional piano pedal markings for more conventional ones. Second, in the viola parts I decided to eliminate several rehearsal numbers that fell in the center of multi-measure rests, instead opting to block the entirety of those rests together. I felt able to do this because Lynn’s rehearsal numbers comprise circled measure numbers every five measures, and the engraving program I used lists additional measure numbers at the beginning of each line. Since the rehearsal numbers do not indicate places in the music which are most convenient to begin rehearsing and the performers are in no danger of losing track of the measure numbers in the engraved parts, I felt comfortable omitting rehearsal numbers where necessary to promote greater facility in counting the multi-measure rests.

After finishing my engravings, I rehearsed and performed Conversare and Pleasantry alongside pianist Zerek Dodson. Our main goal in performance was to bring out the unique traits of each piece. As noted at the end of each manuscript, Pleasantry was completed on June 14th in 1982 and Conversare on November 12th in 1983, and yet despite having been written nearly a year and a half apart, the pieces are strikingly similar. In addition to their identical instrumentation, both works are composed in 3/8; a distinctive, lilting time signature. Next, both are written without a true key signature, instead opting for frequent accidentals as the key area shifts throughout each piece. Finally, both pieces end similarly with a crescendo flourish to a held note under a fermata. With so many overlapping features, it was important to draw out what made each piece unique.

Despite their many similarities, Conversare and Pleasantry each have distinct musical moods. Namely, Conversare is carefree and playful while Pleasantry is tender and wistful. These contrasting attitudes exist in both their melodies as well as in their tempos. Conversare is marked at 72bpm to the dotted quarter while Pleasantry is marked at 58bpm. Zerek and I worked to exaggerate the differences in tempo to highlight light-heartedness and tenderness of each piece respectively. Another way we sought contrast in Lynn’s works for viola and piano was through the use of articulation. In performing Conversare I chose to play with brushier bow strokes to create a sense of lightness, whereas in Pleasantry I preferred smoother, more connected strokes. These details coupled with George Lynn’s lyrical writing combined to create what I believe is an effective performance which highlights Lynn’s compositional range.

Getting to explore George Lynn’s works for viola and piano has been an extraordinary experience. This project has enabled me to further my skills engraving and editing music as well as provided me with the humbling opportunity to perform two unpublished works. It was an honor to bring Conversare fra Viola ed Piano and Pleasantry for Viola and Piano to life, transforming them from a collection of handwritten, yellowed manuscript papers in a box in the sub-basement of the Norlin Library to two vibrant recorded performances available for the public to enjoy. It is my hope that my performance editions of Conversare and Pleasantry will enable other violists to enjoy these two beautiful pieces as I have done. I am truly grateful to Lynn’s family for their efforts in preserving George Lynn’s music and legacy and look forward to the many wonderful research projects involving this collection yet to come.