Stories from fossil seeds

Reflections on a semester of undergraduate research in paleobotany by Abel Campos

Plants in the fossil record

Life has existed on Earth for a really, really long time. So long that It has become extremely difficult for us to determine just how old different groups of organisms actually are. One of the only viable options for us as scientists to figure out the age of different organisms is by studying the fossils they have left behind. Unfortunately, fossil evidence is not always readily available to researchers. Now, you may be thinking to yourself, “There seems to be plenty of evidence, look at all the dinosaur fossils that have been found!”. And while it is true that an incredible body of knowledge has been accumulated around the dinosaurs, other very interesting and important groups of organisms, due to a variety of different factors, have been studied significantly less than dinosaurs. One of these understudied groups is plants.

Plants are one of the oldest and most widespread groups of organisms on Earth, yet compared to dinosaurs, we have learned very little about the plants of the past from their fossil records. This is partly due to the fact that plant parts, like leaves and stems, don’t fossilize as well as bones, giving scientists less of a chance to find good plant fossils. However, this does not mean that there are no plant fossils at all, and another reason that little has been inferred about plants from their fossil record is that scientists have not paid the plant fossil record sufficient attention. The fact that plants maybe aren’t as exciting as things like dinosaurs, as well as the fact that plant fossils are less common, have deterred scientists from really studying the plant fossil record. The Fossils, Fruits and Seeds project is an attempt to direct the eyes of the scientific community towards the plant fossil record, and show that overlooking these fossils is not a viable option if we want to know the details of how life evolved on Earth.

My Experience Contributing to the Project

I joined the lab and started contributing to the Fossils, Fruits and Seeds project, under the mentorship of Rocio Deanna in January of 2021. It was the first time I had ever worked in a professional research environment, so the first month was dedicated to learning about the current state of research on the tomato family (Solanaceae) by reading about the most important findings from the last 20 years and discussing them with my mentor. Over the course of those discussions, it started to become clear that one of the foremost gaps in understanding was the timeline during which major groups in the tomato family evolved.

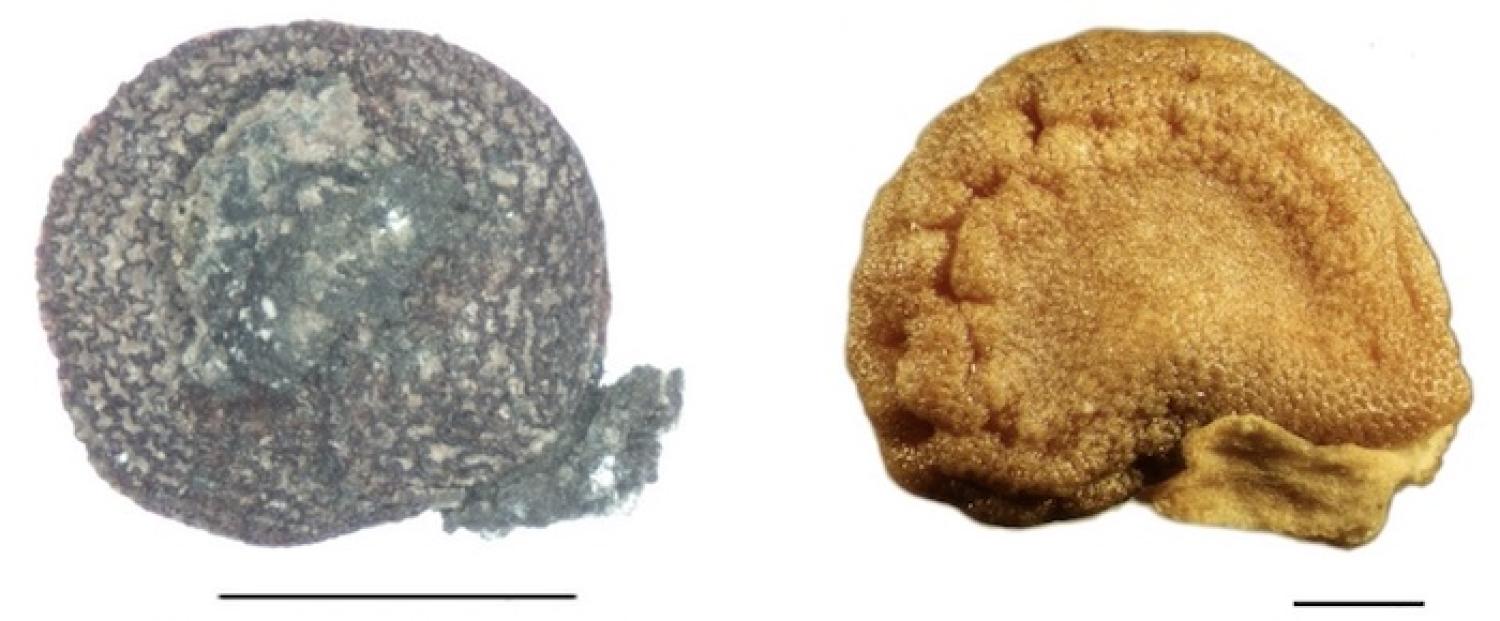

After becoming oriented with the current state of the field, I started learning techniques for data collection. One of the goals of the project is to review the tomato family’s fossil record and create a database of fossil fruit and seed characteristics. So, I was introduced to the twelve traits that would help indicate to us whether these seeds were members of the tomato family or not. I was then taught how to digitally check each fossil seed specimen for those traits. I spent the remaining three months working my way through the seed specimens that had not yet been analyzed (like the ones below) and checking each of them for the twelve traits we had decided on, and recording the absence or presence of those traits in our database. By determining whether these fossil seeds displayed traits indicative of the tomato family, we can start to get an idea of how long those kinds of traits have been present on earth, and when they started to appear. It also gives us the chance to appreciate just how morphologically diverse seeds can be, even within the same family.

On the right, a fossil seed described as Physalis pliocenica (within the tomatillo genus) and on the left, a seed from an extant species of angel's trumpet, Datura inoxia. The fossil seed has an attached structure on the bottom right that could be a food reward body for dispersers (an elaiosome). Elaisomes are only found in Datura, so the fossil might belong in Datura instead of Physalis. Photos by Rocío Deanna. |

Next Steps for the Project

Now that the data collection of fossil seed traits is beginning to wrap up, we will be moving into fruit trait data collection in the summer. Since the currently known fruit fossils from the tomato family are older than the seed fossils, the compilation of a database of fossil fruit traits is a crucial step towards advancing our understanding of how and when the family’s most iconic traits started to evolve. A compilation of fossil fruit traits in conjunction with the data we have collected on fossil seeds will allow us to begin narrowing down the age of the tomato family. As more and more studies like this one are carried out, each pursuing the evolutionary history of specific group of plants, we as a scientific community will be able to build a more comprehensive picture of how flowering plants evolved on Earth.