Community-based monitoring

To ensure meaningful outcomes, we seek to engage Communities to co-produce knowledge of river conditions and climate vulnerabilities. We follow both the Principles for Conducting Research in the Arctic (IARPC, 2018) and the Guidelines for Considering Traditional Knowledges in Climate Change Initiatives (Chief et al., 2015).

Community-based monitoring will entail:

Expanding and enhancing water quality and temperature monitoring by indigenous communities and the USGS

Using monitoring data to assess and calibrate models

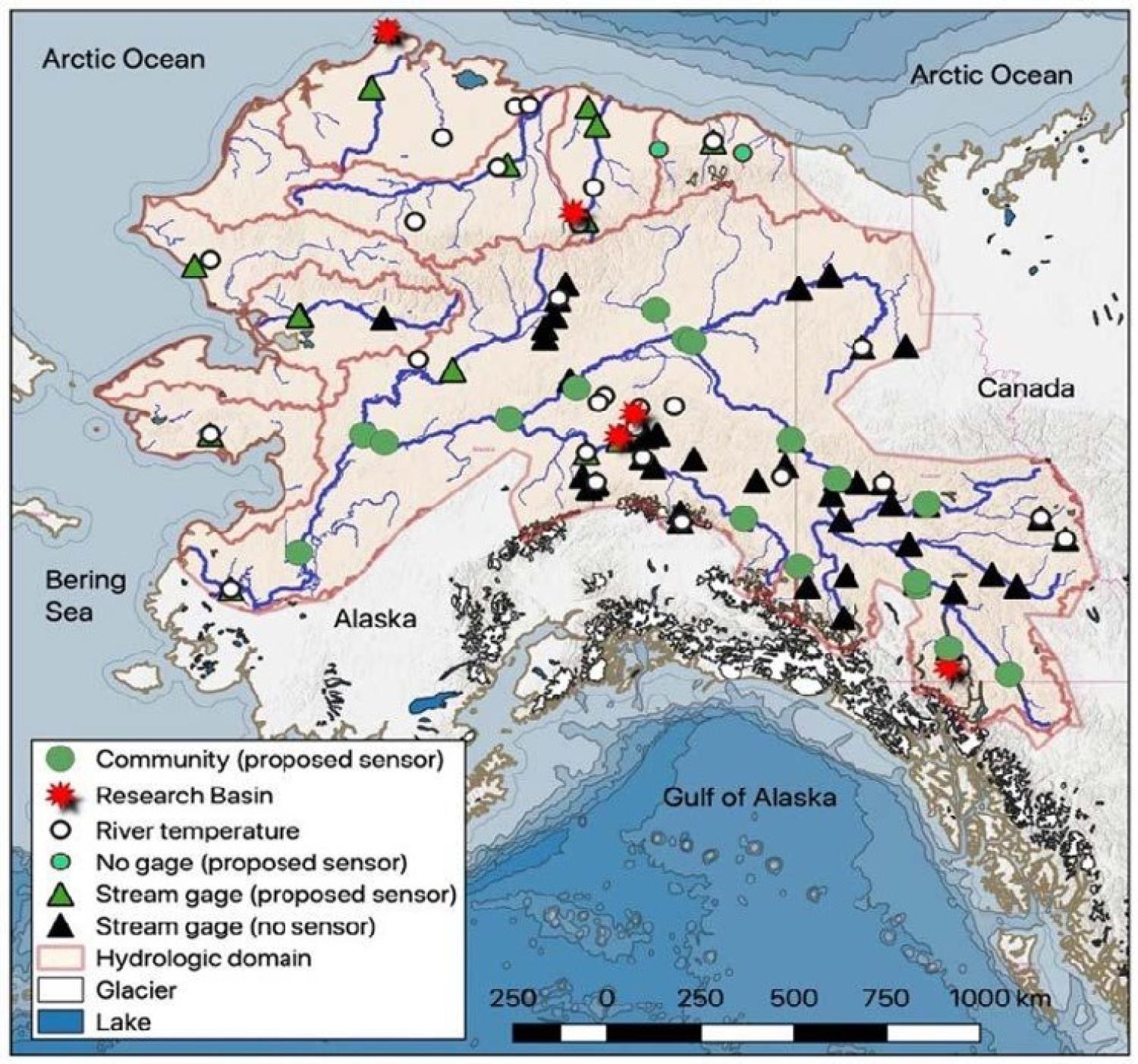

In 2021, working with the USGS and the Yukon River Inter-Tribal Watershed Council (YRITWC), water sensors were deployed across the Yukon River basin and other northern Alaskan rivers. These sensors collect data that will help us learn how changes in precipitation, snowmelt, glacier melt and permafrost thaw combine to impact river conditions.

The work was not easy, and those in the field faced challenges. Navigating another summer with Covid-19, the YRITWC implemented a rigorous Covid-19 safety travel protocol. This included weekly negative Covid-19 test results to ensure the health of our project partner communities and to comply with Tribal Council travel mandates. Combining the logistical challenges of rural communities’ limited air flight availability, delayed air cargo delivery, a fragile communication system, and timely Covid-19 testing made a coordinated field effort across a landscape such as the Yukon River basin especially challenging.

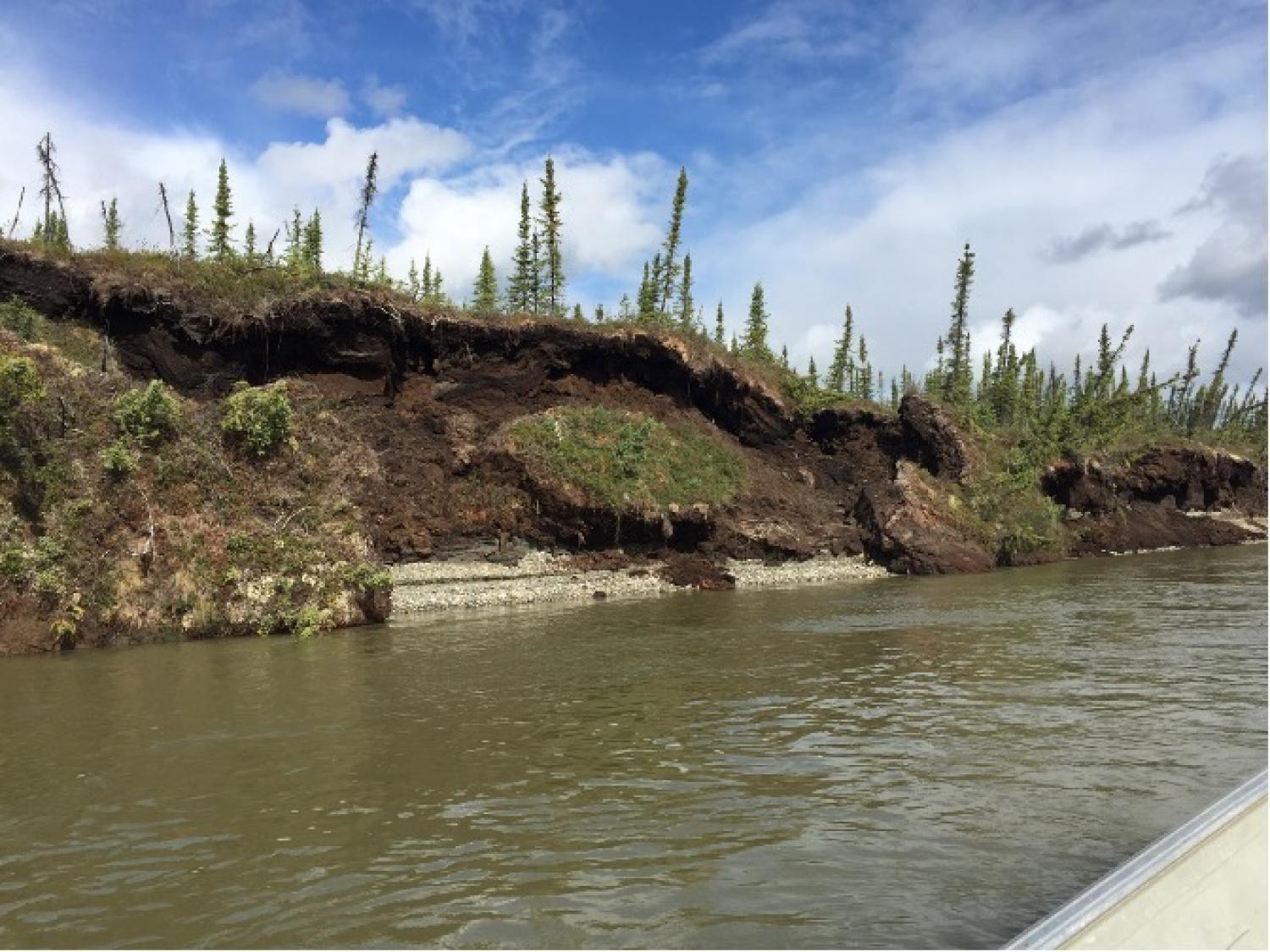

Another challenge we experienced was with our sensor deployment and retrievement due to weather conditions, fluctuation of water levels, unstable riverbanks, and sedimentation influx from increased river erosion across the regions. Overall, the summer was colder and wetter but we experienced regional differences with regards to river water levels. The combination of high snowpack and rapid snowmelt at the Southern Lake region caused widespread flooding that even surpassed high water levels from 2007. Meanwhile, drier weather and low water levels were observed for major Yukon River tributaries originating from the Brooks Range. Throughout the fall months, high precipitation contributes to flooding and accelerated river erosion at many Alaska Interior rivers, demonstrating complex variation over this large region.