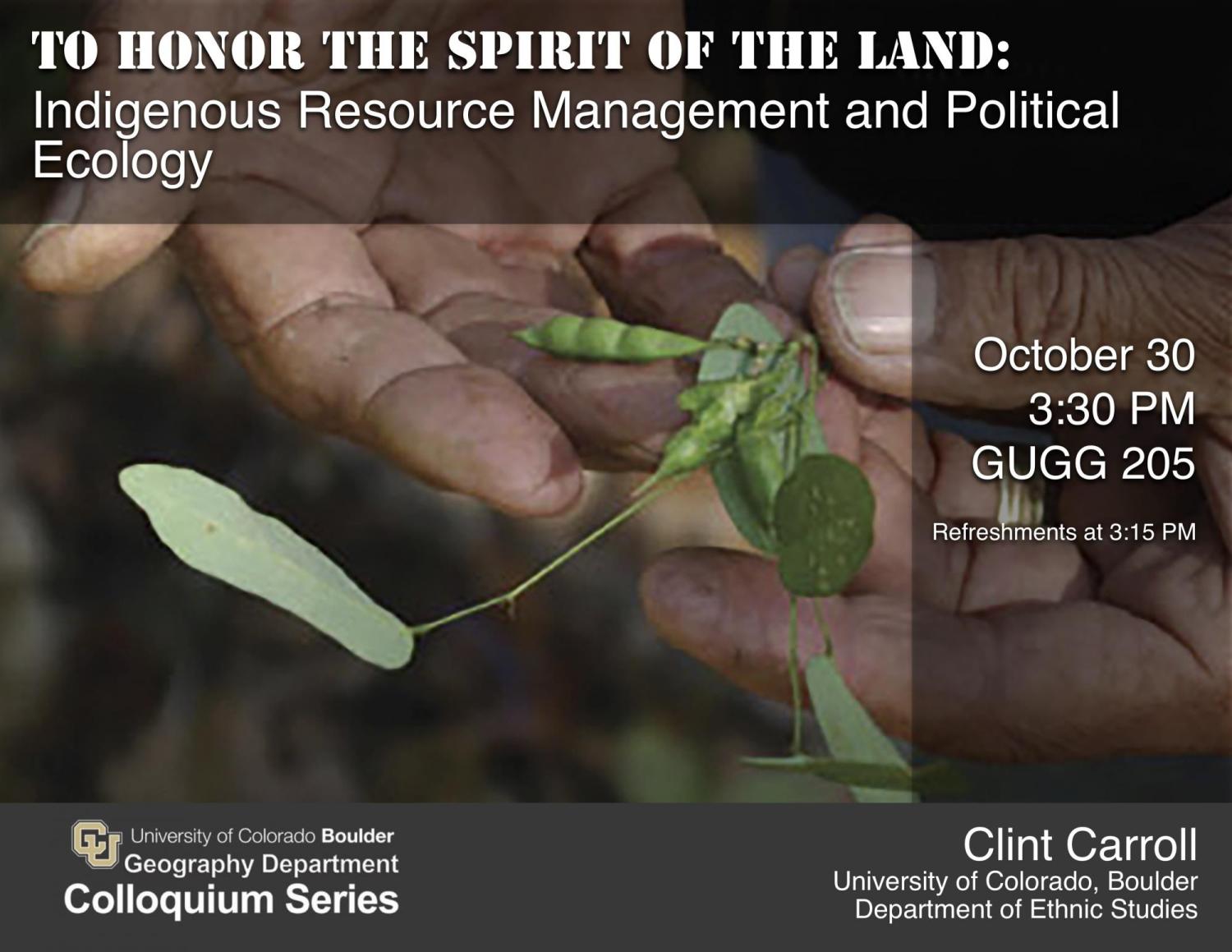

To Honor the Spirit of the Land: Indigenous Resource Management and Political Ecology

Abstract: With the increasing sophistication of tribal environmental programs that seek to protect and reclaim authority over lands and resources, how are Native nations reconciling the institutional framework of “resource management” with traditional teachings on proper relationships with nonhuman beings? How might the intersection of political ecology and Indigenous studies inform approaches to this issue and other similar dynamics throughout Native communities? Clint Carroll will address these questions through a presentation on his recently published book, Roots of Our Renewal: Ethnobotany and Cherokee Environmental Governance (University of Minnesota Press, 2015).

From the Press: In Roots of Our Renewal, Clint Carroll tells how Cherokee people have developed material, spiritual, and political ties with the lands they have inhabited since removal from their homelands in the southeastern United States. Although the forced relocation of the late 1830s had devastating consequences for Cherokee society, Carroll shows that the reconstituted Cherokee Nation west of the Mississippi eventually cultivated a special connection to the new land—a connection that is reflected in its management of natural resources. Until now, scant attention has been paid to the interplay between tribal natural resource management programs and governance models. Carroll is particularly interested in indigenous environmental governance along the continuum of resource-based and relationship-based practices and relates how the Cherokee Nation, while protecting tribal lands, is also incorporating associations with the nonhuman world. Carroll describes how the work of an elders’ advisory group has been instrumental to this goal since its formation in 2008. An enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation, Carroll draws from his ethnographic observations of Cherokee government–community partnerships during the past ten years. He argues that indigenous appropriations of modern state forms can articulate alternative ways of interacting with and “governing” the environment.