South Italian Vase Painting

The art of vase painting is generally associated with the vase painting workshops in Athens (Attica), but by the end of the 5th century B.C.E. and increasingly toward the middle of the 4th century B.C.E., Attic vase painters were producing fewer and fewer painted vessels. A new center of painted vase production arose in workshops in the Greek colonies of South Italy. Up to this point, exporting Attic vases to Italy had been an affluent business. In fact, the majority of Attic Greek vases on display in museums and held in private collections were recovered from tombs in Italy and more specifically from tombs in Etruria, a region in central Italy. South Italian pottery workshops, however, experienced a dramatic and rapid surge in the 4th century B.C.E. and by about 320 B.C.E., exports of vases from the Greek mainland had largely ceased and South Italian vase painting rose to prominence. South Italian vases are key to our knowledge of everyday life for both Greek and indigenous populations living in Italy and Sicily in the 4th century B.C.E.

In general, we define South Italian vases as red-figure vases produced by Greek and local artisans living and working in South Italy and Sicily from the late 5th to the late 4th century B.C.E. These pots are further categorized by their more specific areas of production in South Italy and Sicily. Four major workshops were firmly established by ca. 350 B.C.E. in Apulia, Lucania, Campania, Paestum (also known as Poseidonia), and Sicily. Most vases produced from these workshops remained in use locally and were rarely exported beyond the surrounding Italian regions. Apulian workshops were the largest and the most successful, to judge by the fact that more than one-half of extant South Italian vases come from Apulia.

The most popular shapes for South Italian vases were the amphora, the hydria, the lekythos, and the krater. Certain shapes, such as the volute krater and the Panathenaic amphora, had fallen out of production in mainland Greece, yet gained significant popularity in South Italy. The volute krater in particular was popular in Apulia and could be made very large, reaching to heights between 1 and 1.5 meters.

Characteristic of South Italian vase painting are innovative compositions and a variety of narrative viewpoints. These characteristics are most commonly seen on vases exhibiting the most popular themes of either funerary ritual or theatrical imitation on larger vessels. An Apulian volute krater now in the British Museum, for example, depicts a funerary scene of a young man and is contemporary to the tombs found in nearby Taras (Tarentum). The young man stands in front of a ritual water basin, with a tomb behind him depicted in the guise of a miniature temple. Apulian decorations tend to be elaborate and ornamental, often with very detailed floral patterns, theatrical masks adding detail to the volute handles, and bird heads, such as swans, decorating handle joins.

In addition to the popular funerary scenes, South Italian pottery workshops also produced vessels with theatrical scenes and, in particular, scenes taken from the tragedies of the later 5th century B.C.E. Athenian playwright Euripides, whose works enjoyed unprecedented success during the 4th century B.C.E. Other theatrical scenes depicted burlesque phlyax plays, which were popular in the region at this time. Phlyax scenes were rendered in typically caricature fashion, showing characters wearing grotesque masks and prosthetic phalluses in parodies of popular and well-known heroes from 5th century B.C.E. Athens.

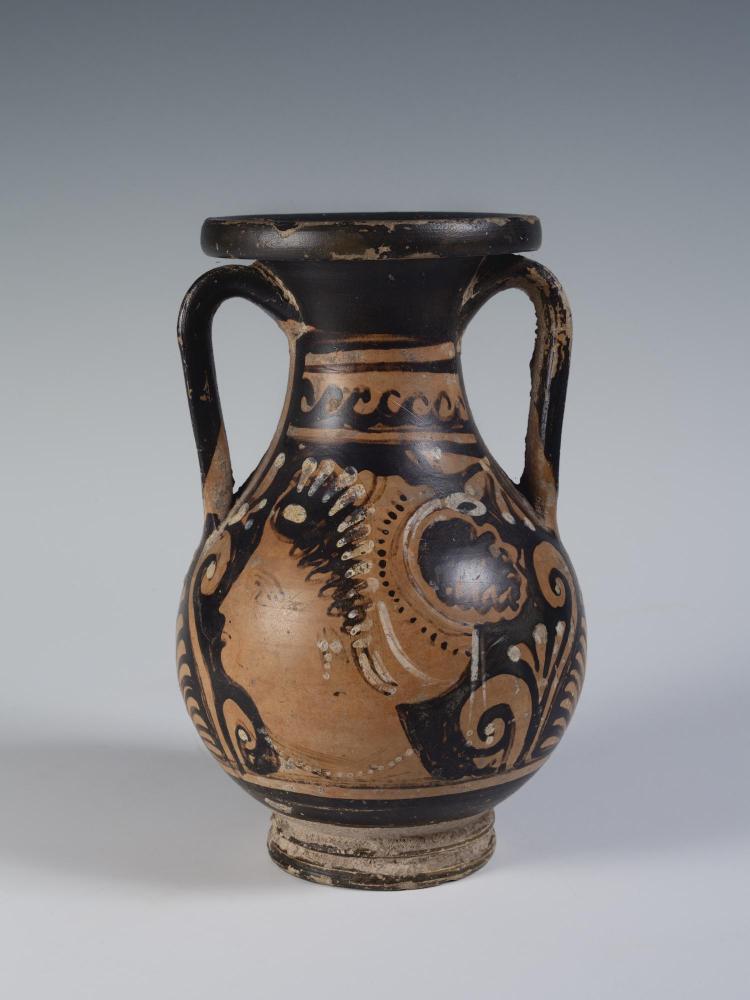

Smaller vessels, such as pelikai, were decorated with a different set of themes. As on an Apulian pelike in the CU Art Museum's collection (pictured here), popular themes for these vessels included single female figures in profile or women in the process of adorning themselves in preparation for a wedding ceremony. These depictions of women are interesting variations on more typical depictions of women on Greek vases and may inform modern viewers about life for women in South Italy and Sicily.

It is interesting to observe how characteristically Greek these vessels and their producers were in spite of their South Italian production. Two principal vase painters, known to us because they signed some of their vessels, are Assteas and Python. These names suggest that the potters were Greek. What is more, the themes depicted on their signed vessels, and especially the theatrical scenes, are well-understood Greek subjects, which suggests that the painters were well-acquainted with Greek culture. A calyx krater signed by Assteas formerly in J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu, for example, shows Europa, a consort of Zeus, riding on the back of a white bull, a critical component of her mythology; a Dionysiac scene adorns the other side.

This essay was written to accompany a collection of Greek artifacts at the CU Art Museum.

References

- A.D. Trendall, "Farce and Tragedy in South Italian Vase-Painting" in eds. Tom Rasmussen and Nigel Spivey, Looking at Greek Vases (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991): 151-182.

- A.D. Trendall, Red Figure Vases of South Italy and Sicily, A Handbook (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1989): 7-25