When passion flares, a freedom and duty to speak

The pursuit and sharing of knowledge should be shielded from the brute force of public opinion, and when public pressure spikes, history shows, the choices of individual people really matter

Like a metronome, Albert A. Bartlett ticked off a steady beat of bad news, methodically outlining the truth and consequences of exponential human population growth. Then, he noted that the methods to reduce population are generally undesirable: for instance, pandemic, famine, war.

Rhetorically, Bartlett asked the classroom full of young people, “Who wants more war?”

A testosterone-addled boy sitting nearby roared: “War! Yeah!”

Clint Talbott is assistant dean for communications in the CU Boulder College of Arts and Sciences and a former journalist.

Unfazed, Bartlett replied:

“Anyone who cheers for war has never lived through one.”

Having thus silenced the would-be warrior, Bartlett continued to explain the exponential function and its implications for humankind.

This was 1979, and I didn’t immediately grasp the symbolism of this brief exchange. It encapsulated core functions of academe—the pursuit and sharing of knowledge, careful and critical thinking, respectful and open debate.

Truth, logic and debate would become the foundation of my career, first in journalism, then as a communicator for the university.

But as a high-school sophomore from Montrose, Colorado, my perspective was constrained; I was just a kid on a recruiting tour of the University of Colorado Boulder. I met professors, toured facilities and spent a few days at CU because, unusually, I’d gotten decent grades in Algebra II.

A so-so student at the age of 17, I had no intention of going to college, let alone the state’s top university. I planned to attend vo-tech school and become an auto mechanic. Two things stood in my way: One, I was a bad mechanic, and two, I took a journalism course as a high-school senior and was immediately hooked.

It was compelling—intoxicating, really—to set up shop in the marketplace of ideas. Learning, discussing and debating ideas made them, and me, come alive. I was part of something bigger than myself. Work had Meaning.

Over time, I saw the extent to which public discourse was refined and distilled in academe. Discussions that occurred nationally also happened on campus, but often in more concentrated, more rigorous, sometimes more contentious forms.

Speech on matters of critical public concern should be “robust, uninhibited and wide-open,” former U.S. Supreme Court Justice William Brennan famously wrote. Discourse can reach peak vibrancy on campus, partly because of universities’ commitment to free speech and academic freedom.

Intellectual vigor is one reason, perhaps, that academe has long drawn criticism. By design, it protects unpopular ideas and unwelcome lines of inquiry. Why? Because the pursuit of knowledge should be shielded from the brutish whimsy of public opinion.

History teaches us this. Galileo committed heresy by reporting what was empirically true and what is now utterly uncontroversial.

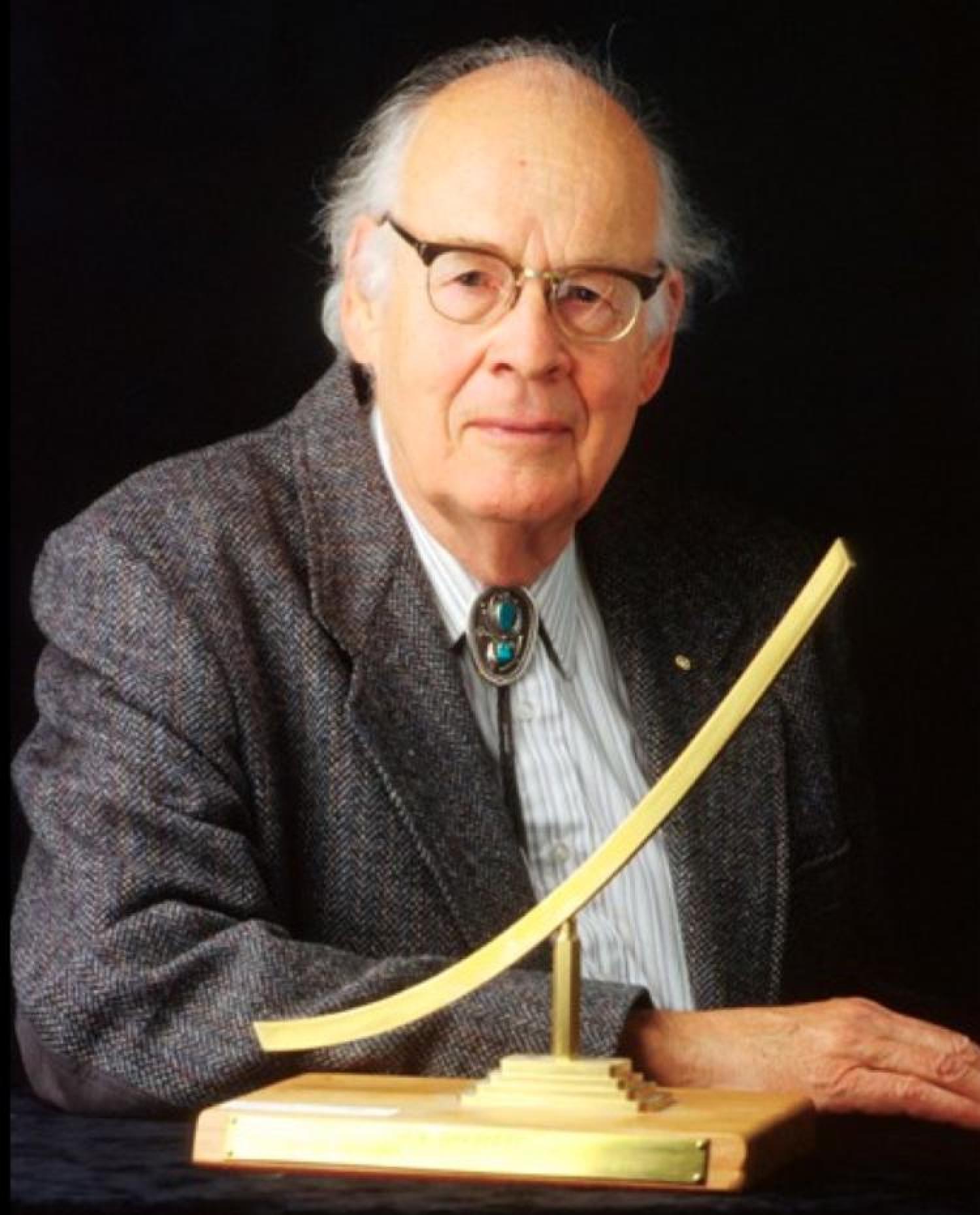

Professor Bartlett campaigned for population control for decades. He gave the talk I observed more than 1,742 times before he died in 2013. It’s been viewed on YouTube more than 5.2 million times.

The late Professor Al Bartlett, who worked on the Manhattan Project as a young scientist, used his scientific acumen to pursue growth control both globally and locally.

Bartlett, who worked on the Manhattan Project as a young scientist, used his scientific acumen to pursue growth control both globally and locally. In Boulder, for instance, he spearheaded the “blue line” initiative, which prevented the city from delivering treated water above about 5,750 in elevation in the foothills. Without water, real-estate development shrivels.

Today, Bartlett’s legacy is, literally, easy to see.

“Albert Bartlett’s influence is unmistakable in the foothills surrounding Boulder. With few exceptions, one sees trees, grasses and rock,” the Daily Camera wrote in 2006 as it gave him a lifetime-achievement award.

Advocating for population control—and controlled growth generally—can be controversial. But as a university professor, he had wide latitude to take such positions. The Boulder Valley and society at large are the better for full academic freedom and freedom of speech.

Critics have long argued otherwise. Again and again, higher education generally, and the University of Colorado in particular, have attracted strong public criticism and furtive government scrutiny. Some such episodes seem relevant today.

The feds are watching, and so are the people

The late Howard Higman, who was a professor of sociology and founder of the CU Conference on World Affairs, hit the FBI’s radar—and later Time magazine’s—in 1960.

In the middle of a sociology lecture at CU, “the most conspicuous member of the class,” Marilyn Van Derbur, then 22, Miss America of 1958, asked Higman to comment on Masters of Deceit, a book by J. Edgar Hoover, the longtime director of the FBI.

Time characterized the episode this way: “The professor obliged by launching into a denunciation of the FBI, and for two days, embattled factions of the 190-student class, led by Marilyn and the professor, argued the reputation of the FBI. Proving Marilyn’s point that the FBI is always on the spot, Author Hoover sent Marilyn an autographed copy of Masters of Deceit with the message: ‘Your actions in confronting error with truth are in keeping with the highest traditions of academic freedom.’”

Higman said, “I smelled a plot coming, but it is not my habit to duck questions.” The Van Derbur report became one of many that the FBI carefully recorded in its thick file on Higman.

The late Howard Higman, a CU Boulder professor of sociology and founder of the CU Conference on World Affairs, hit the FBI’s radar—and later Time magazine’s—in 1960.

That file was publicly revealed via the U.S. Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), which helps to ensure that people can see how the government spends public money conducting the people’s business.

It so happens that one key architect of FOIA was Samuel J. Archibald, a CU alumnus who served as chief of staff of the Government Information Subcommittee in the U.S. House of Representatives. Archibald led the investigation of government secrecy that paved the way to the passage of FOIA in 1966. And, in a later chapter of his life, Archibald was my journalism professor at CU Boulder.

FOIA and its state counterpart, the Colorado Open Records Act (CORA), help us understand, more accurately and fully, what happened during key junctures of our history. In the Higman case, federal law enforcement spent decades monitoring a professor who was suspected of no crime.

This happened repeatedly. Folsom Field is named after a once-famous CU football coach, Frederick Folsom. His son, the late Franklin Folsom, a CU alumnus and longtime Boulder resident, was executive secretary to the League of American Writers from 1937 through 1942.

That job, and his activism for peace, drew the interest of the FBI, which recorded that several anonymous informants said Franklin Folsom was known by aliases. Those allegations were false. Secret informants also reported that his wife, Mary Elting, spent years working in a job she never held.

As Franklin Folsom noted in a 1981 Denver Post guest opinion, the FBI did get his home address and phone number right. “How much this information cost the taxpayer, no one will ever know,” he wrote.

Similarly, there was Kenneth E. Boulding, who was a distinguished professor of economics at CU. The 1993 New York Times obituary marking Boulding’s death called him a “much honored but unorthodox economist, philosopher and poet.”

As the Times noted, his textbook Economic Analysis “blended Keynesian and neoclassical economic theory into a coherent synthesis.”

But Boulding was also against war. He was, after all, a Quaker. His advocacy for peace drew the attention of the FBI, as one of my FOIA requests revealed. Starting in 1942, the government launched an investigation of Boulding. The files on him noted, for instance, that Boulding complained about “the downtrodden Negro and constantly protested that he should have equal rights with the whites.”

The FBI also noted that Boulding once advocated for the elimination of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). In no case did the activities of Higman, Folsom or Boulding amount to “subversion,” much less a crime.

In these cases, warrantless (and unconstitutional) spying seemed not to have hindered the subjects’ lives. But national panic and illegal spying on citizens can and does harm people. As we have seen.

The late Kenneth E. Boulding, a distinguished professor of economics at CU Boulder, was described in his 1993 New York Times obituary as a “much honored but unorthodox economist, philosopher and poet.”

Red scare

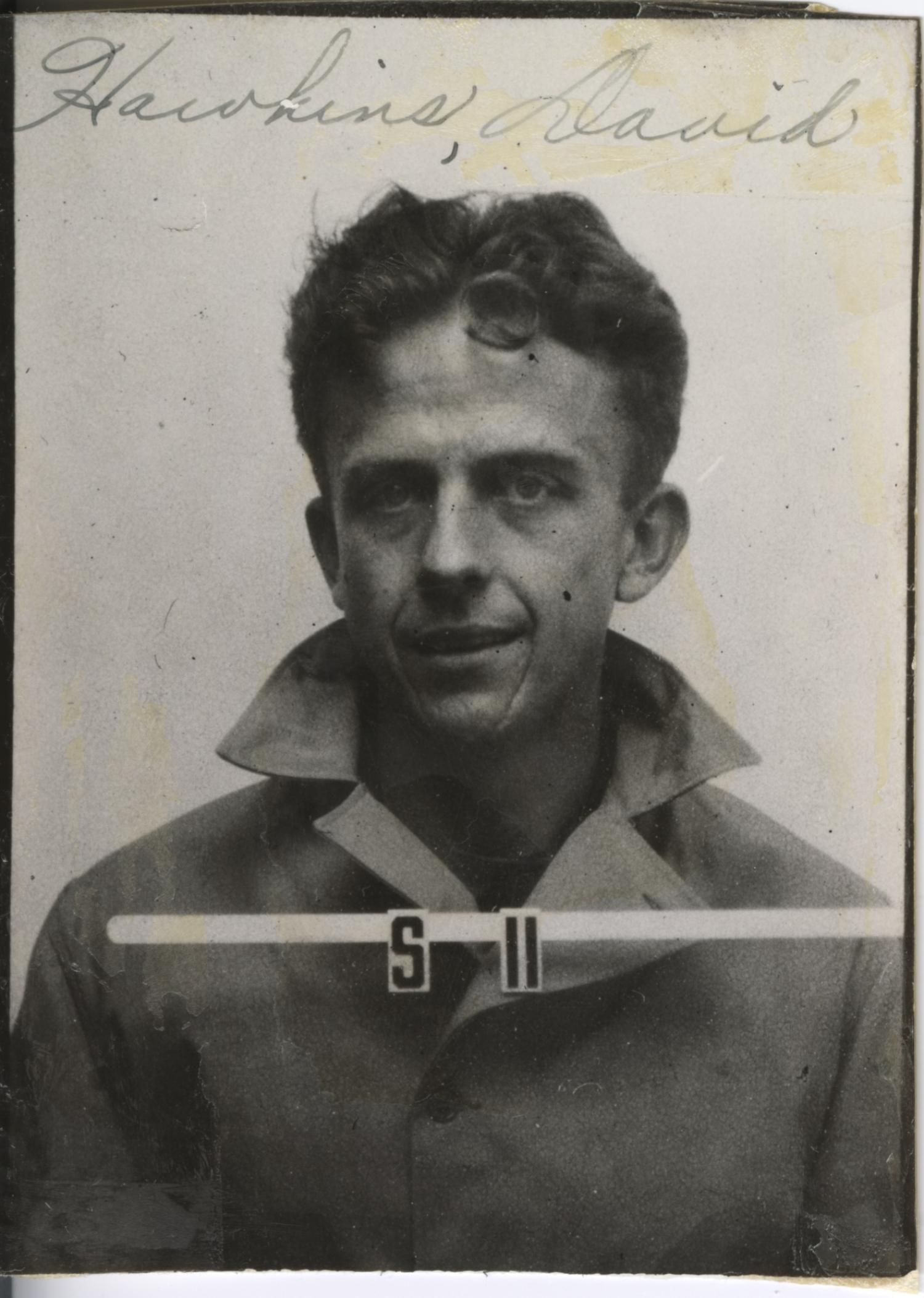

On Dec. 28, 1950, The Denver Post’s banner headline was “CU Prof Reveals Red Link.” The story reported that David Hawkins, CU philosophy professor, had been called to testify before HUAC.

Hawkins admitted that he had joined the Communist Party as a 25-year-old graduate student in California in 1938 but that he’d resigned and stopped paying dues in 1943. Some historians speculate that HUAC summoned Hawkins in an attempt to tie J. Robert Oppenheimer, who led the Manhattan Project, to communism.

The Post’s editorial board argued that CU must determine Hawkins’ loyalty to “American stands of life and to the American ideal of free and honest education.”

State legislators, including Boulder Rep. A.W. Hewett, proposed legislation that would have cut off Communists from any source of state money. As a centennial history of CU noted, Hewett claimed there were “all shades of Reds” at the university.

Colorado’s attorney general ruled that professors should be forced to sign a loyalty oath that was originally enacted in 1921, during an earlier red scare. Eager to quell the rising public concern and possibly to discourage state lawmakers from doing the same, the CU Board of Regents launched an investigation of Communist or otherwise “subversive” influences on campus.

The regents hired two former FBI agents to conduct the investigation. Their report and its recommendations were kept secret—so secret that the report itself was stored in a safe deposit box in the First National Bank of Boulder, and a regent could review the report only upon a majority vote of the board.

After the former FBI men completed their secret probe, the regents voted to retain Hawkins, stating that his actions (which were protected by the First Amendment) were not a firing offense.

But the university did fire Irving Goodman, an assistant professor of chemistry who won Guggenheim fellowships in 1949 and 1950. The regents said Goodman had been a Communist during part of his service at the university and that Goodman had lied about this.

Goodman called those charges “calumny” and said he’d honestly answered all questions about his politics when CU President Robert Stearns quizzed him in 1947.

It wasn’t divulged, at that time, whether the regents’ secret investigation found more damning material.

Similarly, philosophy instructor Morris Judd was fired in late 1951. The stated reason was incompetence and “pedestrian” teaching.

At the time, Judd revealed that he’d been interviewed by the former FBI agents. They asked him if he were a member of the communist party. He said he was not. They asked if he’d ever been a member. He declined to answer, as was his First Amendment right.

Once fired, Judd left academe, never to teach again.

The late CU philosophy instructor Morris Judd (right) declined to answer, per his First Amendment right, when asked by FBI agents if he'd ever been a member of the communist party.

Opening the safe deposit box

But questions remained, even in 2002, when I was working as a columnist for the Boulder Daily Camera. Paul Levitt, a professor of English, was a CU student during the McCarthy era and suggested that I file a Colorado Open Records Act request for the report.

I did this. The university declined to release the report, arguing that it contained legal advice and private information. To its credit, the Camera sued for the report’s release.

In an initial court hearing, the Boulder County judge who was reviewing the secret report said that if it indeed contained legal advice, it was subtle. The judge, who seemed skeptical of the university’s arguments, said she’d issue a ruling within a week.

Before the judge ruled, however, the regents voted to release the report in full. After 51 years, the report finally revealed that Judd was not, in fact, fired for incompetence; he was fired because he was merely suspected—with no compelling evidence—of being “subversive.”

The allegations were insubstantial. One unnamed source told the private investigators that Judd was “90 percent or better a probable Communist” in 1946. Another anonymous accuser said he was “of the opinion” that a “subversive” group had met at Judd’s Boulder home in 1947.

None of this proved that Judd was (or had been) a Communist. Nor did it yield any meaningful data on Judd’s fitness to teach philosophy. The only empirical measure of Judd’s abilities—the assessment of his fellow faculty members—found him more than fit to teach. In fact, his colleagues judged him the best young teacher in his department.

Politics can circumscribe academic freedom. Stearns himself revealed this in a now-declassified interview conducted at the Pentagon in 1954 (released via my FOIA request). Stearns admitted that he had fired “leftist or pinkish” faculty members, including Judd.

Stearns also told the Pentagon official that he’d kept tabs on the alleged subversives after their firing: “My connections … have always been close with the military and with the FBI, particularly, and I have kept them informed on each of these men, so they know well what they are doing and where they have gone,” Stearns said.

The late David Hawkins, a CU philosophy professor, was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1950 and admitted that he had joined the Communist Party as a 25-year-old graduate student in California in 1938 but that he’d resigned and stopped paying dues in 1943.

That is a startling admission. If we take his words at face value, it’s hard to fathom why Stearns did not fire tenured professors against whom there was stronger evidence of Communist Party affiliation. Instead, he targeted non-tenured instructors whom he might have seen as expendable.

As some have suggested, that might have been a stratagem designed to protect core faculty members from rabidly red-baiting lawmakers. Stearns might have believed he’d chosen the lesser of two evils, sacrificing non-tenured faculty to protect those with tenure.

All of that was moot to Goodman and Judd, who sustained permanent damage. Goodman later reported falling into poverty. Judd’s experience was similar.

“I suffered the loss of my academic career. This investigation was a horrendous violation not only of my rights, but of the tradition of academic freedom,” Judd said when the university honored him in 2002, adding:

“That secret and unwarranted procedure has been compounded by the years of secrecy in withholding the report from the public.”

The red scare episode was both a crucible and a parable. When the fuller account of what happened emerged in 2002, people debated how to reconcile this newly released information—firing faculty without due cause or process—with the ideals they held dear.

Some said the university made the right choice, arguing that making a public show of firing two junior faculty surely prevented the state Legislature from launching an investigation that could have unjustly destroyed even more careers. Such an investigation had, indeed, been threatened.

Others argued that contemporary observers can’t fully appreciate the pressures of 1951. One authoritative voice emphasizing that point was Albert Bartlett, who made a lasting—and positive—impression on me in 1979.

As public records from the university, the FBI, the Pentagon and other agencies provided compelling evidence that Judd, Goodman and others were sacrificed for the sake of a perceived greater good, English Professor Paul Levitt and others urged that the university rename the Stearns Award, the university’s highest faculty award.

Like Levitt, Bartlett was on campus during the red scare, which he called “one of the very dark periods in American history and the history of the University of Colorado.”

But Bartlett argued against stripping the Stearns name from the faculty award. Writing in the Camera in 2002, Bartlett recalled that one of his first letters to the editor of that newspaper concerned Sen. Joseph McCarthy, pointing out that “a specific allegation made by McCarthy was known by me to be a lie.”

“After the letter was published, someone counseled me about such writing,” Bartlett recalled. “I was untenured and uncertain, but the message was clear. So I turned my back to tend to my own business.”

Bartlett pointed out that in 1951, faculty groups did not condemn the firings of junior faculty members. Some professors, including Jacob Van Ek, then dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, did object. But many were silent. Most turned their backs, tending to their own business.

As Bartlett noted, if the “faculty governance bodies of 50 years ago failed to stop these tragic firings, then the faculty of 2002 can apologize for failing to speak out against the injustice” in 1951.

And again, Bartlett faced a contentious moment with cool reason, verifiable facts and respectful debate. In so doing, he offered a lesson that we must heed:

In times of national hysteria, when reason fails and madness prevails, good citizens are obliged to stand and speak.

Clint Talbott is a 1985 journalism graduate of CU Boulder. He spent 14 years working at the now-defunct Colorado Daily and 10 years at the Daily Camera and was a 1998 Pulitzer Prize finalist for editorial writing. He has worked for the College of Arts and Sciences since 2008.

Did you enjoy this article? Subscribe to our newsletter. Passionate about arts and sciences? Show your support.