Western wildfires destroyed 246% more homes and buildings over the past decade

Scientists explain why wildfires are happening, why we can't put out every fire and how to move forward in an ever-changing climate

It can be tempting to think that the recent wildfire disasters in communities across the West were unlucky, one-off events, but evidence is accumulating that points to a trend.

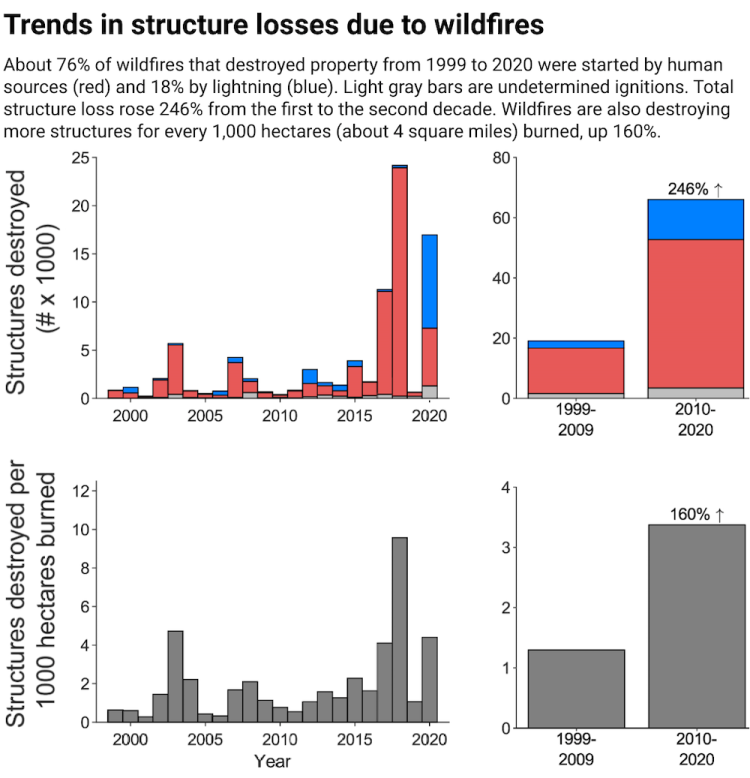

In a new study, we found a 246% increase in the number of homes and structures destroyed by wildfires in the contiguous Western U.S. between the past two decades, 1999-2009 and 2010-2020.

This trend is strongly influenced by major fires in 2017, 2018 and 2020, including destructive fires in Paradise and Santa Rosa, California, and in Colorado, Oregon and Washington. In fact, in nearly every Western state, more homes and buildings were destroyed by wildfire over the past decade than the decade before, revealing increasing vulnerability to wildfire disasters.

What explains the increasing home and structure loss?

Surprisingly, it’s not just the trend of burning more area, or simply more homes being built where fires historically burned. While those trends play a role, increasing home and structure loss is outpacing both.

As fire scientists, we have spent decades studying the causes and impacts of wildfires, in both the recent and more distant past. It’s clear that the current wildfire crisis in the Western U.S. has human fingerprints all over it. In our view, now more than ever, humanity needs to understand its role.

Wildfires are becoming more destructive

From 1999 to 2009, an average of 1.3 structures were destroyed for every 4 square miles burned (1,000 hectares, or 10 square kilometers). This average more than doubled to 3.4 during the following decade, 2010-2020.

Nearly every Western state lost more structures for every square mile burned, with the exception of New Mexico and Arizona.

Humans increasingly cause destructive wildfires

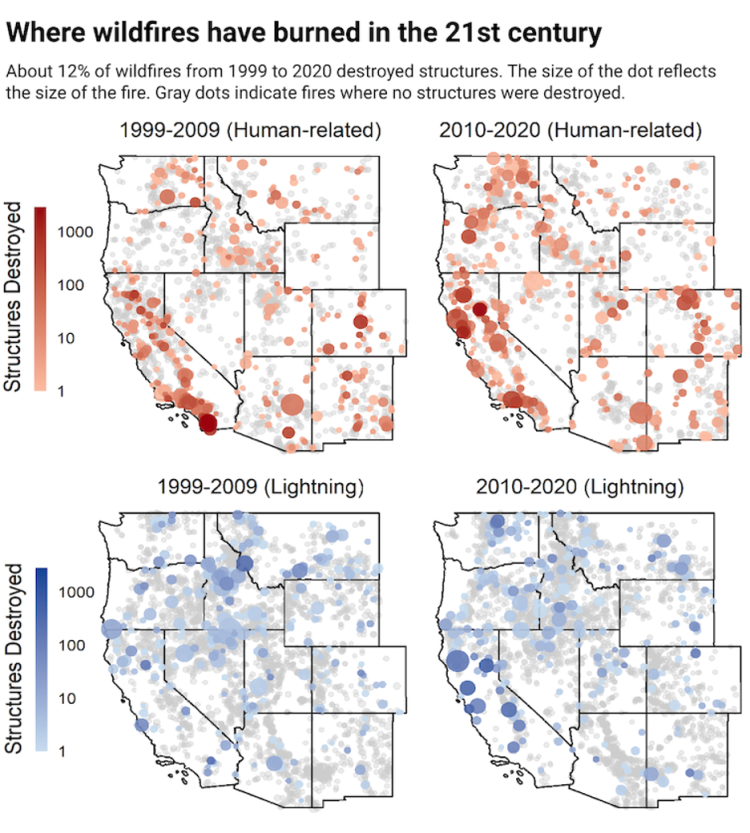

Given the damage from the wildfires you hear about on the news, you may be surprised to learn that 88% of wildfires in the West over the past two decades destroyed zero structures. This is, in part, because the majority of area burned (65%) is still due to lightning-ignited wildfires, often in remote areas.

But among wildfires that do burn homes or other structures, humans play a disproportionate role – 76% over the past two decades were started by unplanned human-related ignitions, including backyard burning, downed power lines and campfires. The area burned from human-related ignitions rose 51% between 1999-2009 and 2010-2020.

This is important because wildfires started by human activities or infrastructure have vastly different impacts and characteristics that can make them more destructive.

Unplanned human ignitions typically occur near buildings and tend to burn in grasses that dry out easily and burn quickly. And people have built more homes and buildings in areas surrounded by flammable vegetation, with the number of structures up by 40% over the past two decades across the West, with every state contributing to the trend.

Human-caused wildfires also expand the fire season beyond the summer months when lightning is most common, and they are particularly destructive during late summer and fall when they overlap with periods of high winds.

As a result, of all the wildfires that destroy structures in the West, human-caused events typically destroy over 10 times more structures for every square mile burned, compared to lighting-caused events.

The December 2021 Marshall Fire that destroyed more than 1,000 homes and buildings in the suburbs near Boulder, Colorado, fit this pattern to a T. Powerful winds sent the fire racing through neighborhoods and vegetation that was unusually dry for late December.

As human-caused climate change leaves vegetation more flammable later into each year, the consequences of accidental ignitions are magnified.

Putting out all fires isn’t the answer

This might make it easy to think that if we just put out all fires, we would be safer. Yet a focus on stopping wildfires at all costs is, in part, what got the West into its current predicament. Fire risks just accumulate for the future.

The amount of flammable vegetation has increased in many regions because of an absence of burning due to emphasizing fire suppression, preventing Indigenous fire stewardship and a fear of fire in any context, well exemplified by Smokey Bear. Putting out every fire quickly removes the positive, beneficial effects of fires in Western ecosystems, including clearing away hazardous fuels so future fires burn less intensely.

How to reduce risk of destructive wildfires

The good news is that people have the ability to affect change, now. Preventing wildfire disasters necessarily means minimizing unplanned human-related ignitions. And it requires more than Smokey Bear’s message that “only you can prevent forest fires.” Infrastructure, like downed power lines, has caused some of the deadliest wildfires in recent years.

Reducing wildfire risks across communities, states and regions requires transformative changes beyond individual actions. We need innovative approaches and perspectives for how we build, provide power and manage lands, as well as mechanisms that ensure changes work across socioeconomic levels.

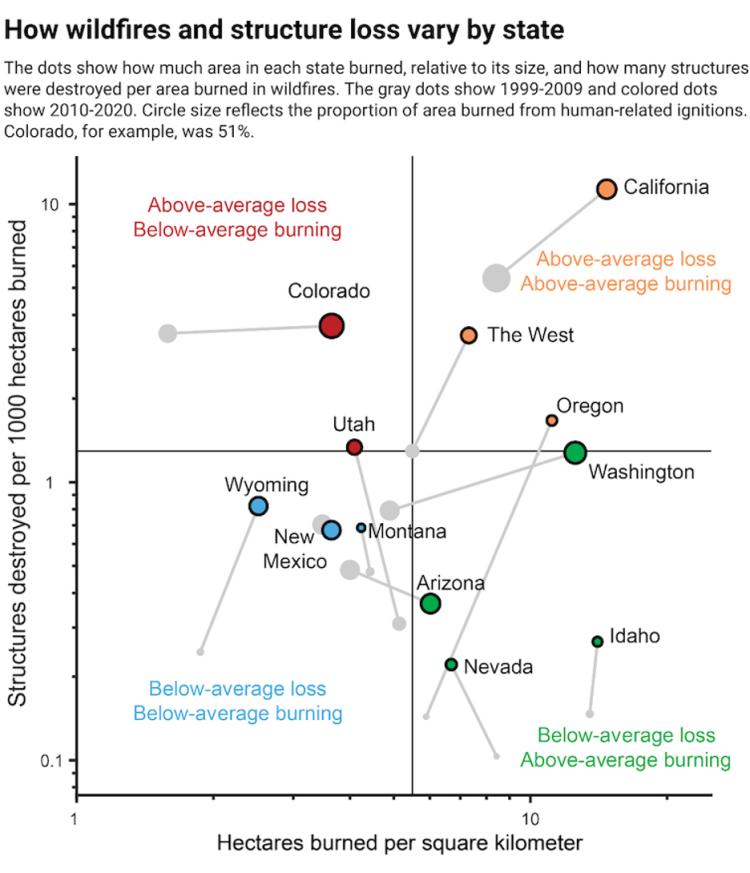

Actions to reduce risk will vary, since how people live and how wildfires burn vary widely across the West.

States with large tracts of land with little development, like Idaho and Nevada, can accommodate widespread burning, largely from lighting ignition, with little structure loss.

California and Colorado, for example, require different approaches and priorities. Growing communities can carefully plan if and how they build in flammable landscapes, support wildfire management for risks and benefits, and improve firefighting efforts when wildfires do threaten communities.

Climate change remains the elephant in the room. Left unaddressed, warmer, drier conditions will exacerbate challenges of living with wildfires. And yet we can’t wait. Addressing climate change can be paired with reducing risks immediately to live more safely in an increasingly flammable West.

Philip Higuera, Professor of Fire Ecology, University of Montana; Jennifer Balch, Associate Professor of Geography and Director, Earth Lab, University of Colorado Boulder; Maxwell Cook, Ph.D. Student, Dept. of Geography, University of Colorado Boulder, and Natasha Stavros, Director of the Earth Lab Analytics Hub, University of Colorado Boulder

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.