Unlocking the secrets of the East Antarctic ice sheet

Climate change may soon cause the sleepy giant to evolve, new research finds

Climate researchers are gravely concerned about the state of the Greenland ice sheet and the West Antarctic ice sheet, which have collectively lost billions of tons of ice over the last three decades because of atmospheric warming and warm ocean currents. That ice loss, in turn, has contributed to rising sea levels.

But they’ve generally paid less attention to the East Antarctic ice sheet, the largest ice sheet—and the world’s largest reservoir of freshwater—because past work has suggested that it’s less vulnerable to climate change than the other two and may be growing, not shrinking. If it were to completely melt, this behemoth structure, which is 10 times larger than the West Antarctic ice sheet, would cause global sea levels to rise by 52 meters (about 170 feet).

Now, though, there are signs that the East Antarctic ice sheet may be more susceptible to climate change than previously thought, according to an international team of scientists, including one from the University of Colorado Boulder. Their findings of the understudied ice sheet are out today in the journal Nature.

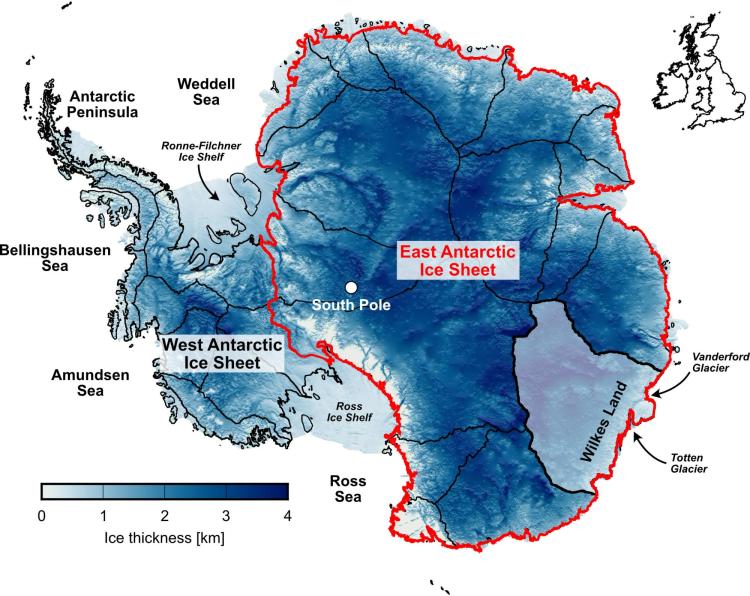

At the top of the page: Vanderford Glacier reflection (Jones). Above: A location map of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (Guy Paxman).

“There’s a huge amount of interest from funding agencies, from governments, from the media in Greenland and West Antarctica—and for very good reasons,” says Jan Lenaerts, a CU Boulder assistant professor in the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences (ATOC) and one of the study’s co-authors.

“They’re changing. They’re dramatic. They’re discharging all this water and ice into the ocean, and it looks phenomenal and scary—and it is scary. But then there’s this third elephant in the room, this huge big brother, just waiting to be discovered.”

Scientists do predict that, in the short term, the East Antarctic ice sheet will likely remain stable because increased snowfall will offset any mass loss (in the form of melting snow and ice, as well as icebergs calving off into the ocean) caused by global warming. By 2100, they predict the East Antarctic ice sheet could contribute about 2 centimeters (0.79 inches) to sea level, which is much less than projections for the Greenland or West Antarctic ice sheets.

“The ice sheet will, to a large degree, stay as it is—namely a sleepy, but not sleeping, giant where things might change but not in a very dramatic fashion,” says Lenaerts. “We will keep the East Antarctic ice sheet dormant, and we will have to focus on the other two ice sheets.”

But in the longer term—beyond the year 2100—the future of the East Antarctic ice sheet will largely depend on global greenhouse gas emissions and temperature trends.

“The fate of the East Antarctic ice sheet remains very much in our hands,” says Chris Stokes, a professor of geography, sea level, ice and climate at the United Kingdom’s Durham University and the study’s lead author.

If global temperatures rise more than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels—the upper limit set by the Paris Agreement on climate change—the East Antarctic ice sheet could contribute as much as one to three meters (3 to 10 feet) to global sea levels by 2300, and two to five meters (6.5 to 16 feet) by 2500.

But if temperature increases stay below 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels, then the ice sheet could avoid the worst effects of global warming. Under that scenario, the ice sheet would contribute less than half a meter to sea level rise by 2500, according to the researchers.

“If we exceed that temperature boundary, we might initiate processes that are irreversible,” Lenaerts says.

To reach these conclusions, the scientists analyzed projections from numerical model simulations, as well as historical data and current observations. And though the study was a good first step toward forecasting the future of the East Antarctic ice sheet, they say it also highlighted gaps in our knowledge and research efforts in this region.

Mount Brown south ice core camp, Princess Elizabeth Land, East Antarctica (N. Abram).

“There’s definitely more work needed to synthesize the data and improve the modeling,” says Lenaerts. “The envelope of uncertainty, the spectrum of the models going into the future, is as wide as it can get. I don’t think there’s any place on Earth that has as much uncertainty of the future of climate change and its impacts than East Antarctica.”

Still, they hope the paper will help bring much-needed attention to the East Antarctic ice sheet, whether in the form of increased research funding, greater emphasis among climate researchers or more general interest from governments and members of the public.

Researchers still have a lot of unanswered questions about the mammoth structure and, as the climate continues to change, they need all the data they can get to make accurate predictions about the fate of the planet.

“It’s disappointing how little we know about a huge part of our climate system,” says Lenaerts. “It speaks to my imagination, at least, that there’s this huge ice sheet—the biggest reservoir of freshwater on Earth—and we don’t really talk about it as much because it’s not changing as much. But that doesn’t mean it’s not important.”