Fish ear bones hold clues to Antarctic Ocean health

Assistant professor Cassandra Brooks has received an NSF CAREER award, the organization recently announced

Cassandra Brooks, assistant professor of environmental studies at the University of Colorado Boulder, was in the negotiating room when the Ross Sea in Antarctica became the world’s largest marine protected area (MPA) in 2016.

The deliberations had been tense, Brooks says, involving more than 24 countries, each with its own aims for the waters surrounding the icy southern continent—commercial, environmental or otherwise.

“We’d be close to reaching an agreement,” Brooks remembers, “and then one country would raise their flag and say, ‘No, I don’t agree.’”

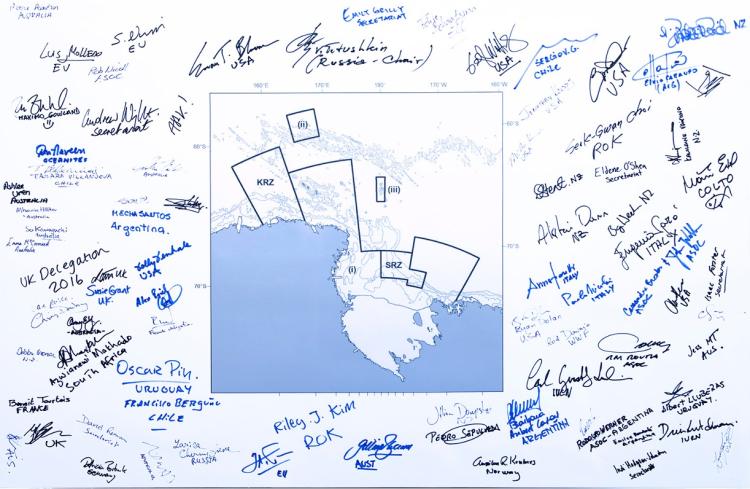

At the top of the page: Environmental studies assistant professor Cassandra Brooks has won an NSF CAREER award to conduct research on Antarctic toothfish. Above: Map of Ross Sea MPA signed by those present during the negotiations. Brooks’ signature is on the right side in blue (Photo courtesy Cassandra Brooks).

The geopolitical gymnastics carried on for two weeks before the chair of the committee brokering the discussions finally said, “We have it. We have consensus.”

“The room exploded in applause,” Brooks recalls. “People from different countries were hugging each other. Some people were crying. It was one of the most amazing moments of my life.”

Now Brooks has received a Faculty Early Career Development Program (CAREER) award from the National Science Foundation to examine whether the Ross Sea MPA is doing its job.

Brooks calls the Ross Sea a “global treasure.”

“It is the most productive stretch of the Southern Ocean,” she explains. “Katabatic winds—which are kind of like Boulder’s chinook winds but cold—blow the seasonal sea ice away from the Ross Ice Shelf, creating large pools of open water.”

Then, when the sun finally rises after the long Antarctic winter, Brooks says, it gives rise to a phytoplankton bloom so massive, it can be seen from space.

Hence the Ross Sea’s outsized presence of marine life. “You collectively have more penguins in the Ross Sea than anywhere else,” Brooks says. “You have disproportionate amounts of seals and whales.”

The Ross Sea remains “the most intact large marine ecosystem left in the world,” says Brooks. This is what makes it so valuable to researchers.

“If you don’t know how a healthy system functions,” she says, “how do you know how to effectively conserve it and protect it?”

Yet in the late ‘90s, commercial fishing began to encroach upon the Ross Sea. And one of the most sought-after catches just so happens to be the key to Brooks’ research: the Antarctic toothfish, the Southern Ocean’s top fish predator.

Brooks holding an Antarctic toothfish (Photo courtesy Cassandra Brooks).

There’s a chance you’ve heard of this fish, Brooks says, albeit by a different name. On restaurant menus it’s called Chilean sea bass. “It was a fishmonger who changed the name and then targeted it at high-level, expensive restaurants,” Brooks says. “It’s definitely not a bass!”

According to Brooks, the Antarctic toothfish holds a wealth of information, particularly in its ear bones, called otoliths.

“They are these little bony structures in the fish’s ear, and like any bony structure, they accumulate bone over the course of the fish’s lifetime,” Brooks says. These bones can reveal a fish’s age, where it was born and where it has moved over the course of its life.

And when looked at in the context of a time series, Brooks says, these ear bones can reveal whether a fish’s life history and migration patterns have changed, among other things.

Brooks has more than 40 years of otoliths to study, which have been shared with her by other leading toothfish experts and Antarctic scientists.

“This will be the longest time series that anyone’s ever looked at for the species,” Brooks says. The time series is so long, in fact, that Brooks will be able to analyze otoliths from before the arrival of the Ross Sea fisheries.

Fisheries, Brooks says, can significantly alter a species and the ecosystem. “Longline fisheries tend to target the largest (and oldest) fish and can thus lead to longevity overfishing where the fish tend to be younger and smaller over time.”

This can hinder their reproductive success and have knock-on effects in the wider ecosystem.

“While toothfish are a top fish predator, they are also a key prey species,” Brooks says. “Seal and whale populations depend on these larger fish.”

In other words, Brooks says, otoliths are not just snapshots of the Antarctic toothfish itself. They can serve as health records for the Ross Sea system, which along with the rest of the Antarctic is undergoing impacts from climate change.

“We know the Antarctic marine systems are changing,” Brooks says. “But it is difficult to tease apart the impacts of fishing from climate change. I hope to use the insight provided through examining otoliths over a long time series to better understand these changes and to better evaluate if the boundaries of the Ross Sea MPA are sufficient or need to be changed.”

For Brooks, the most exciting part of the CAREER award is that it funds “the bigger picture about who you are and the work you do.”

Brooks intends to use the award to inform those who make environmental policy, which she admits is easier said than done.

It’s not as simple as doing the science, she says. “Being trained as a scientist, I always thought, if you have sufficient science, policymakers will make decisions based on the science.” She soon discovered that this viewpoint was, in her words, “super naïve” and so decided to become more engaged in the policy process and better navigate the science-policy interface. Currently, for example, she participates in Southern Ocean policy meetings, serving on the delegation of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research.

I hope to use the insight provided through examining otoliths over a long time series to better understand these changes and to better evaluate if the boundaries of the Ross Sea MPA are sufficient or need to be changed.”

Nor is informing environmental policy as simple as educating the public, Brooks claims. And she would know, having earned a graduate certificate in scientific communication and written multiple articles for popular audiences. (She and her husband, nature photographer John Weller, were core members of the Last Ocean Project, a grand-scale media effort that focused on securing protection for the Ross Sea.)

Effecting real change at the policy level, Brooks believes, requires a combination of things: “really cool science,” outreach, public engagement, communication with policymakers, and the training of students. Put these things together, Brooks says, and you have “engaged scholarship”—precisely the kind of scholarship Brooks plans to pursue throughout her career.

“As a person who’s interdisciplinary,” she says, “I’m just so incredibly excited.”

Brooks began her CAREER research on May 1 and will continue it until April 30, 2027.

In the meantime, she says, think twice before ordering the Chilean sea bass.