This is not your junior-high geography

Encompassing South American wildfires, Arctic sea-ice retreat, post-Soviet politics, climate change in Tibet and GIS, CU Boulder geographers keep their fingers on the pulse of a changing world

Humans cause 84 percent of U.S. wildfires and have extended the fire season, a study led by University of Colorado Boulder researcher Jennifer Balch has found. A separate study led by CU Boulder researcher Tania Schoennagel found that U.S. wildfire policy can’t adequately protect people, homes and ecosystems from the longer, hotter fire seasons caused by climate change.

Both studies made national headlines this year after being published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. But readers might be excused for not knowing Balch and Schoennagel’s discipline.

Both are in the CU Boulder Geography Department.

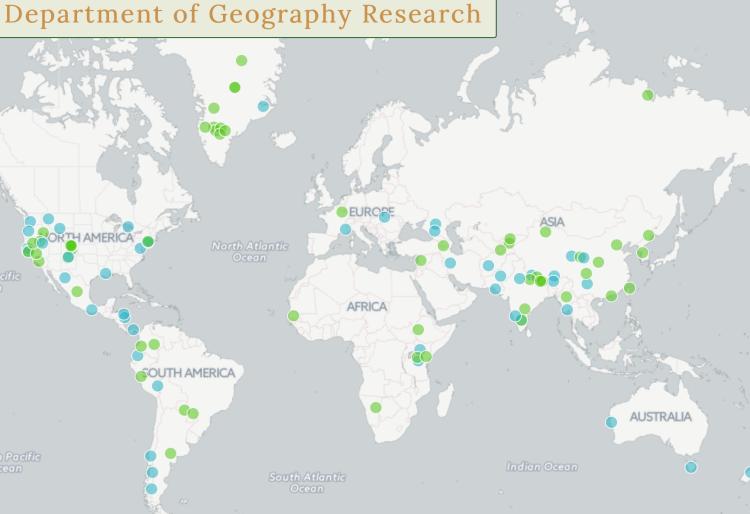

The Department of Geography has created an interactive map showing where in the world faculty and student research is taking place. Click here or on the image to explore.

Though casual observers might think otherwise, students enrolled in a university geography course are not quizzed on the 50 states or systematically prepped to win blue wedges in Trivial Pursuit.

Geography involves knowing where places are, but that’s a starting point, not the substance, of the discipline, geographers note. The study of geography encompasses a wide range of contemporary global problems, including but extending well beyond wildfire.

Emily Yeh, professor and chair of geography, puts it this way:

“We study the drastic loss of sea ice in the Arctic due to climate change, the geopolitics of American aid in Afghanistan, bark beetle outbreaks in the Colorado Rocky Mountains, the relationship between climate change and Mexico-U.S. migration, community mapping and human rights for indigenous peoples, and how to develop better ways to measure social vulnerability to natural hazards, among many other pressing issues.”

Geography is one of the most popular college majors in the United Kingdom. For various historical reasons, the same name recognition has not characterized geography as a discipline in the United States over the past few decades.

“This is changing again, however, with the new prevalence of GIS, geotagged data, and various forms of remote sensing in our everyday lives and, as a result, the rapid rise in employment demand for geospatial analysis,” Yeh observes.

The U.S. Department of Labor projects 35-percent job growth during the next decade for geographers, and Google expects the mapping business to grow by 30 percent annually.

“Our faculty members are at the cutting edge of the new geospatial sciences, using spatial analysis methods in data-intensive research and developing new tools and statistical techniques to more accurately represent and understand social and biophysical space,” Yeh says.

Emily Yeh

But mapping for the “big data” 21st century is only part of what geographers do.

Geographers also study the environmental impacts of fracking, ethno-nationalism in the former Soviet Union, fire regimes in tropical forests and rapid urbanization in China.

“Geography literally means ‘earth writing,’ and it encompasses a holistic approach to the relationships between humans and the earth, society and space,” Yeh adds.

Subdisciplines within geography tackle problems also studied by fields ranging from computer science to cultural anthropology, geology to political science.

“What makes us unique, though, is an integrative lens that pays attention to space and scale,” Yeh says. “Rather than just pointing to where certain places, regions and landscapes are located, we study how they got to be as they are, and how they are related to the world.”

In other words, she adds, geography offers a critical perspective on today’s big questions: “Climate change, migration, inequality, housing, poverty, disease, water, war, energy, and social justice all demand geographical analysis.”

Faculty members in the Geography Department focus their research in four areas:

- Physical geography

- Human geography

- Environment-society relations and

- Geographic information science

Tom Veblen

For example, in physical geography, Tom Veblen, a college professor of distinction and professor of geography, directs the Biogeography Lab, which includes Schoennagel and which studies forest dynamics, partly by analyzing tree rings.

Veblen’s research examines how humans are directly and indirectly altering wildfire activity and other disturbances such as insect outbreaks in the forests of the western United States and in southern South America. Recently, Veblen presented his work in the 110th Distinguished Research Lecture.

Other faculty members in physical geography are well known. One is Waleed Abdalati, director of the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences. Abdalati, who earned his Ph.D. in geography from CU Boulder, previously served as NASA’s chief scientist.

Another is fellow geography alumnus Mark Serreze, who directs the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), which monitors, researches and publicizes the annual Arctic sea-ice minimum. Serreze is one of CU Boulder’s most highly cited researchers.

John O'Loughlin

In human geography, John O’Loughlin is a college professor of distinction and professor of geography and a prominent expert on the political geography of the post-Soviet Union, including Russian and Ukrainian geopolitics, Eurasian quasi-states and ethno-territorial nationalism.

He has also studied the diffusion of democracy, electoral geography, the geography of conflict, and the political geography of Nazi Germany. O’Loughlin is regularly quoted in the mass media about political geography. He also completed a solo bicycling trip across the United States at the age of 65 in 2013, completing the journey in 42 days.

A 2014 internal academic-prioritization report ranked CU Boulder’s department as the top geography department in North America in scholarly achievement.

The department was ranked second in the nation for its doctoral education by the National Research Council.

Gilbert F. White, the late distinguished professor of geography, was one of only four CU Boulder faculty to win the National Medal of Science. White is known as the “father of floodplain management.”

In environment-society relations, chair Yeh is a widely quoted and cited expert on Tibet whose research includes conflicts over access to natural resources, how nationalism affects protection of nature, the social and environmental effects of fencing and privatization of grasslands, the vulnerability of Tibetan herders to climate change, and how and why Tibetans become environmentalists.

She is the author of Taming Tibet: Landscape Transformation and the Gift of Chinese Development, which explores the intersection of political economy and cultural politics of development as a project of state territorialization. It won the 2015 E. Gene Smith Prize for best book on Inner Asia from the Association of Asian Studies. It was also named a “best book of 2014” by Foreign Affairs for the Asia/Pacific region.

Barbara Buttenfield

In geographic-information science, Barbara (Babs) Buttenfield focuses on measuring distance and surface area on terrain surfaces for natural-hazards models. This work becomes significant when modeling flooding, seismic and landslide risks and other environmental hazards that have fundamental impacts on society, safety and natural resources, she stated.

Buttenfield develops algorithms to correct measurements on hilly or rugged terrain, where compromised distance measures might corrupt estimations of hazards such as debris flow and water accumulation. In the rural United States and in developing regions of the world, where fine-resolution terrain data are not available, establishing guidelines for model reliability is needed to protect communities worldwide against hazards.

For more information on geography at CU Boulder, click here.