Unnatural Disasters, Displacement, and the Second-Class Citizen

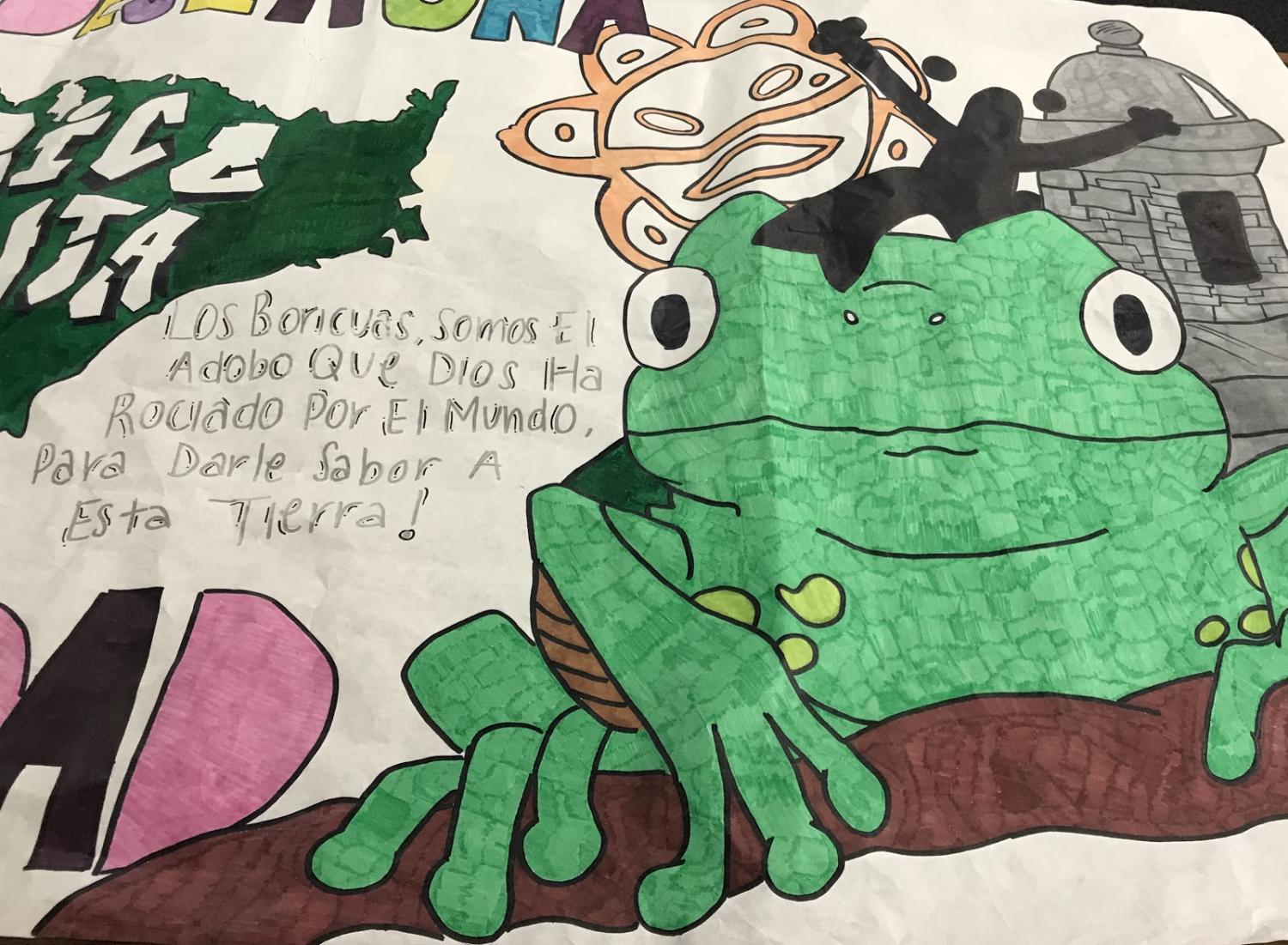

Student artwork celebrating the Puerto Rican community at a student-led holiday event in a Tampa, Florida high school. Los Boricuas somos el adobo que Dios ha rociado por el mundo para darle sabor a esta tierra (We Boricuas are the seasoning that God has sprinkled throughout the world to give flavor to this land).

What happens when students are forced to leave home unexpectedly due to disaster? Do schools serve as spaces of refuge, or do they inadvertently deepen trauma? Our education system can no longer afford to ignore these questions. Natural disasters that were once perceived as isolated incidents are growing in frequency and expected to intensify. As a result, more communities will receive populations displaced by disasters, ultimately revealing pre-existing social inequalities and exposing human-created causes and effects. Last year, Hurricane María wreaked havoc on Puerto Rico, a U.S. colony already suffering from high unemployment and poverty rates. Some scholars, including ourselves, argue that the aftermath of Hurricane María is best described as an unnatural disaster whose effects were compounded by colonialism and its relationship to the island’s natural resources and citizenry. Even though Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens, the arrival of nearly 160,000 Puerto Ricans to the mainland U.S. since Hurricane Maria (including thousands of K-12 students) has revealed the limits of citizenship for racialized subjects in the wake of disaster.

As children and youth from Puerto Rico began enrolling in U.S. schools to avoid long-term disruptions to their education, we carried out a study to examine the effects of displacement on students arriving to Central Florida. While programs and policies were put in place to assist students and families with the transition, participants repeatedly shared how they were met with unfulfilled promises when “welcomed” by the government. For example, families who arrived on humanitarian flights and were given FEMA hotel vouchers endured significant duress as the government regularly threatened to terminate the program with as little as one month’s notice. Teachers shared that many students “came with the hurricane effect”: they were “traumatized”, “didn’t want to be here”, and “their heart [was in] going back to Puerto Rico”. Not only was the abrupt disruption to their lives painful, but the inequitable recovery process on the island and the lack of supports available in receiving communities made the choice of staying or returning complicated. Although many would highlight U.S. citizenship as an advantage that has enabled Puerto Ricans to move back and forth seeking better conditions after the disaster, less attention has been paid to the second-class nature and limitations of that citizenship.

The U.S. government has repeatedly demonstrated reluctance to confer the full benefits of citizenship to Puerto Ricans given the island’s status as a U.S. colony. Hurricane María laid bare this reality. For example, Puerto Rican residents received less aid from FEMA than states recently affected by hurricanes, and more than half of FEMA applications for assistance made by Puerto Ricans were rejected. Scholars in the field of disaster studies often note that disasters do not create inequity but simply reaffirm and deepen structural problems that already existed. Systemic inequities contribute to families with fewer resources being more likely to live in areas that are most vulnerable to the effects of disaster, while also being less likely to receive assistance. The inability (and indifference) of the U.S. government to sufficiently respond to the needs of Puerto Ricans—both those who stayed on the island and those who arrived to the mainland U.S.—reinforces this fact. In fact, throughout the past year, Puerto Ricans in Florida have continually been framed by politicians, media, and the public as foreigners undeserving of short and long-term recovery benefits. What are newly arrived students to make of this sentiment? The message is clear: Citizenship on paper does not automatically confer rights nor a sense of belonging.

What did this second-class citizenship mean for the educational experiences of Puerto Rican students displaced by the hurricane? Although most of the students arriving to Florida were primarily Spanish speaking, they found themselves in a new school system that denies full access to learning in their home language. While individual schools provided language support to newly arrived students, the pressure of taking standardized tests in English was particularly difficult for both teachers and students alike. One teacher, referring to her students, said, “sometimes they’ll think ‘what is wrong with her? Why doesn’t she understand?’ And it’s not what’s wrong, I have to move you forward, and I know you can do it...but it’s as stressful for them as it is for us because we have these standards and accountabilities and all this stuff sitting in the back of our heads”. Even the practice tests leading up to the high-stakes exams presented major challenges. As another teacher shared, “the test does not count for them, per se, but the stress counts for them...and that lives inside of them”. Acknowledging these challenges, the district advocated to the Florida Department of Education to request that students be allowed to take the tests in their home language. Although this option is available and encouraged by the federal Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), the district’s efforts were unsuccessful. In fact, Florida was the last state to receive approval of their plan under ESSA, and the plan does not provide the option to test in languages other than English. For those who chose to pursue a Florida high school diploma, the required standardized tests ultimately assessed not only their content knowledge but their English language proficiency as well. Thus, hundreds of Puerto Rican high school students who arrived at an English-dominant system in their junior and senior years—some only temporarily—could not fully demonstrate their knowledge on these exams.” In some instances, students doubted their ability to pass the exam and chose to receive a Puerto Rico diploma, foregoing access to in-state college tuition opportunities as a result.

The educational effects of Hurricane María are not limited to students in the mainland U.S. More than 200 schools on the island have been closed, and teachers in Florida are expecting what they deemed “another tidal wave of students from Puerto Rico”. Continuing to invoke hurricane imagery, these teachers guessed that their district--home to a pre-established Puerto Rican community--would be “the first spot that’s going to be hit”. There are, of course, striking parallels to what happened to schools in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. An influx of white-led organizations as well as white volunteers and aspiring reformers exploited the disaster for profit, not only displacing residents of color in affected communities but taking over local institutions and privatizing the school system through charter schools. As author Naomi Klein argues, disaster capitalism often takes advantage of “public disorientation” and shock after crises to move corporate initiatives forward. Puerto Rico has been no exception. Beyond the economic crisis that has burdened the island and caused significant out-migration long before the hurricane, the disaster has opened space for investors to buy up land, private companies to profit from recovery efforts, and charter schools to be introduced into the public education system. Disaster-induced migration is far from over.

These examples demonstrate that there are indeed limits to citizenship and full inclusion in society for racialized, colonial subjects. These limits have affected the demands that Puerto Ricans have been able to make on the government to assist with recovery efforts, to provide for families that are displaced, and to support the needs of culturally and linguistically diverse students. Formal citizenship, in other words, has never been enough. We must resist imagining citizenship as a legal document that automatically confers rights to individuals and instead question the ways in which some are systematically excluded from accessing those rights regardless of documentation status.

About the authors

Astrid N. Sambolín Morales is a PhD candidate in the Educational Equity and Cultural Diversity program at the University of Colorado Boulder. Her research interests include translanguaging, bilingual education, critical theories of race, and culturally sustaining/responsive pedagogies.

Molly Hamm-Rodríguez is a PhD student in the Educational Equity and Cultural Diversity program at the University of Colorado Boulder. She is interested in community-based research with youth and families focused on histories and experiences of migration, place, language, and social identity.