The CU Museum is closed we will be opening early in the spring semester.

During this time, collection visits will be available by appointment and other special access requests will be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Please email cumuseum@colorado.edu for more information.

Ross Sea: The Last Ocean

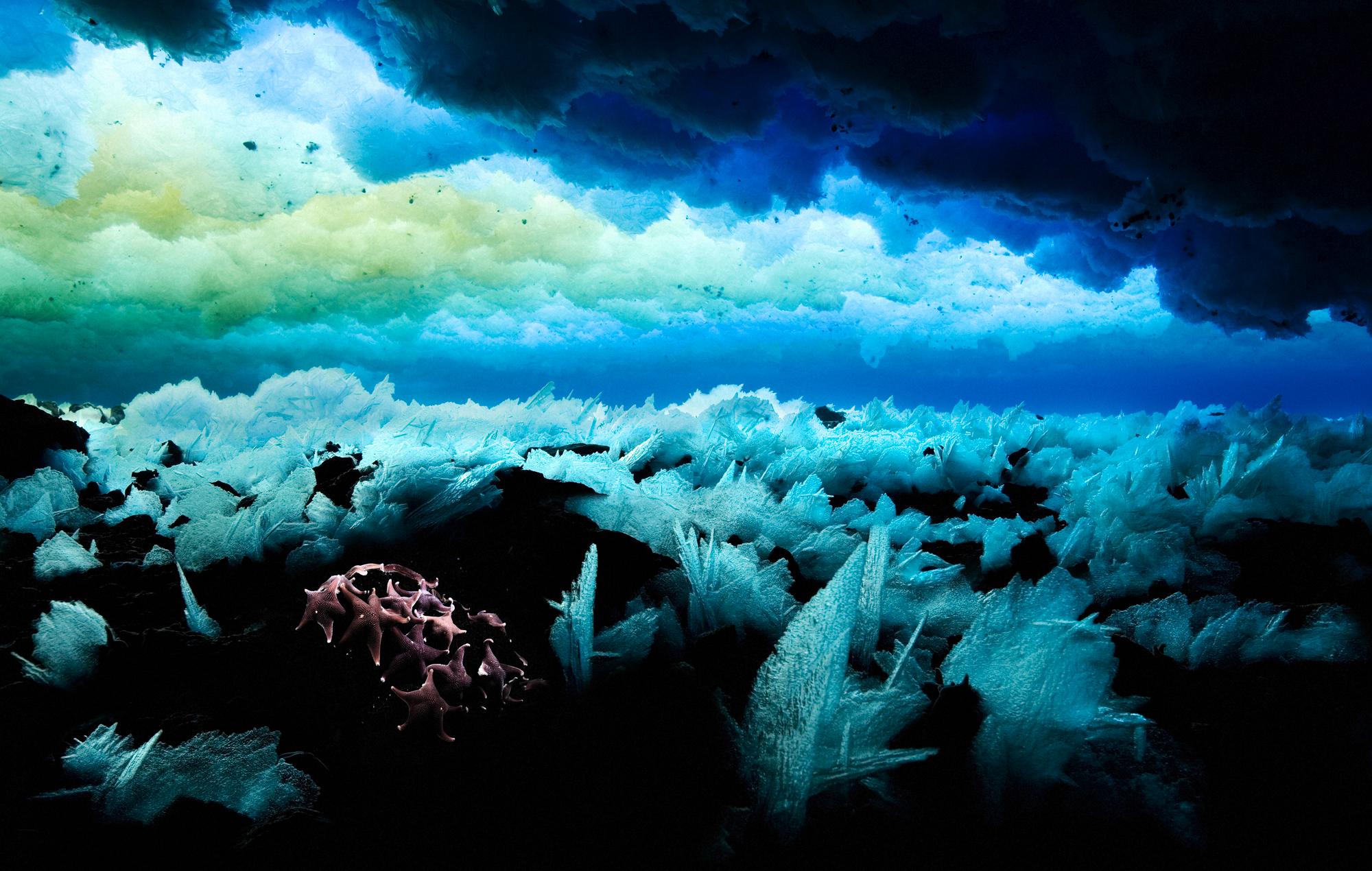

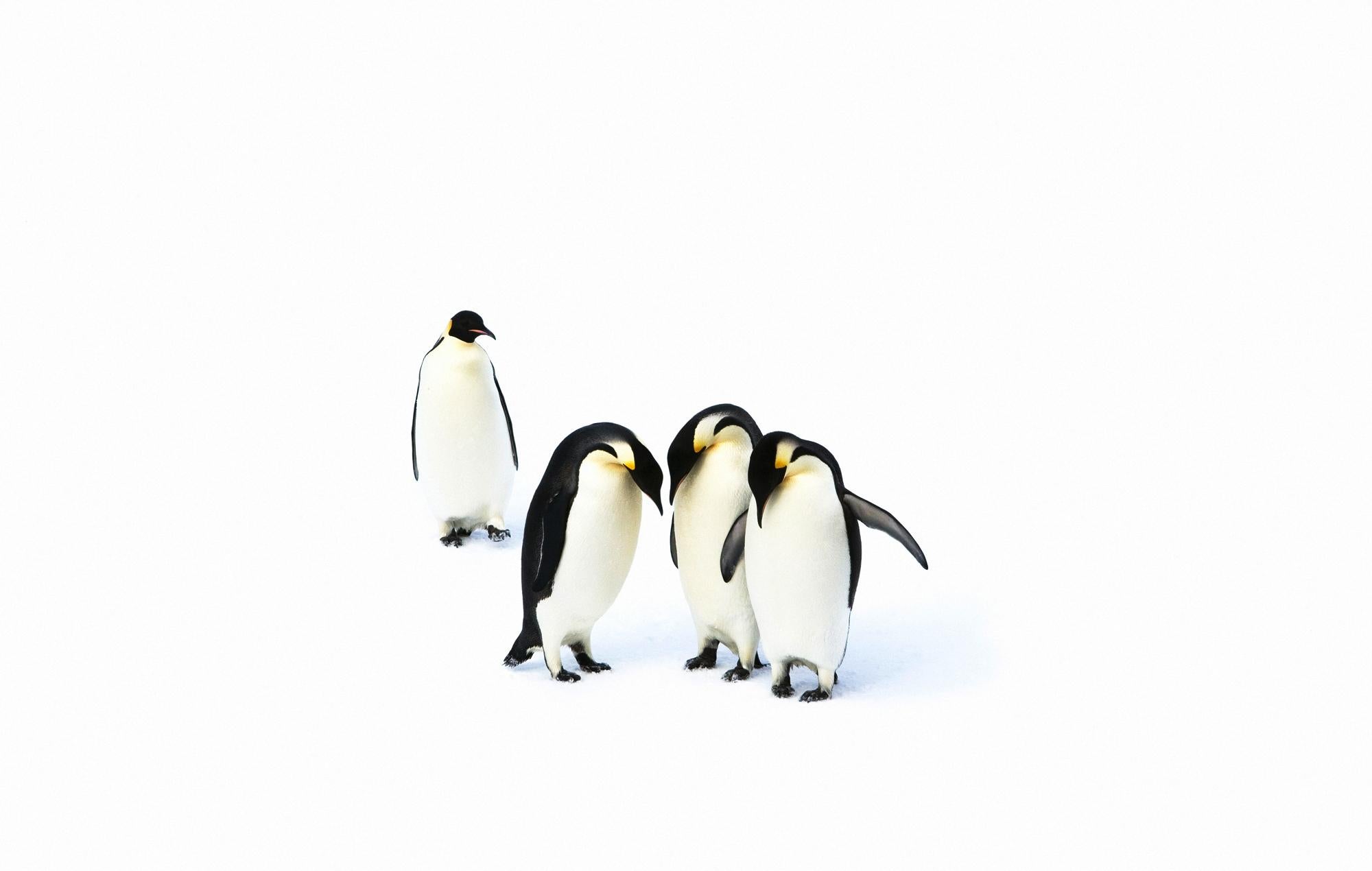

The Ross Sea Antarctica is the last ocean frontier not yet irreversibly harmed by human activity. Pollution, invasive species, and overfishing rendered the region under siege. For over 12 years, Boulder artist John Weller, a team of scientists, policy makers, and ordinary citizens from around the world worked tirelessly to designate the Ross Sea a protected status in an effort to save species and preserve a significant site of climate research. In 2016 their endurance paid off, and the region is now the world’s largest official Marine Protected Area (MPA)! View the slideshow to learn more about the Ross Sea, its biologically diverse ecosystem, and what is possible when we rally together on behalf of our extraordinary planet.

John Weller: Artist Statement

John Weller: Artist Statement

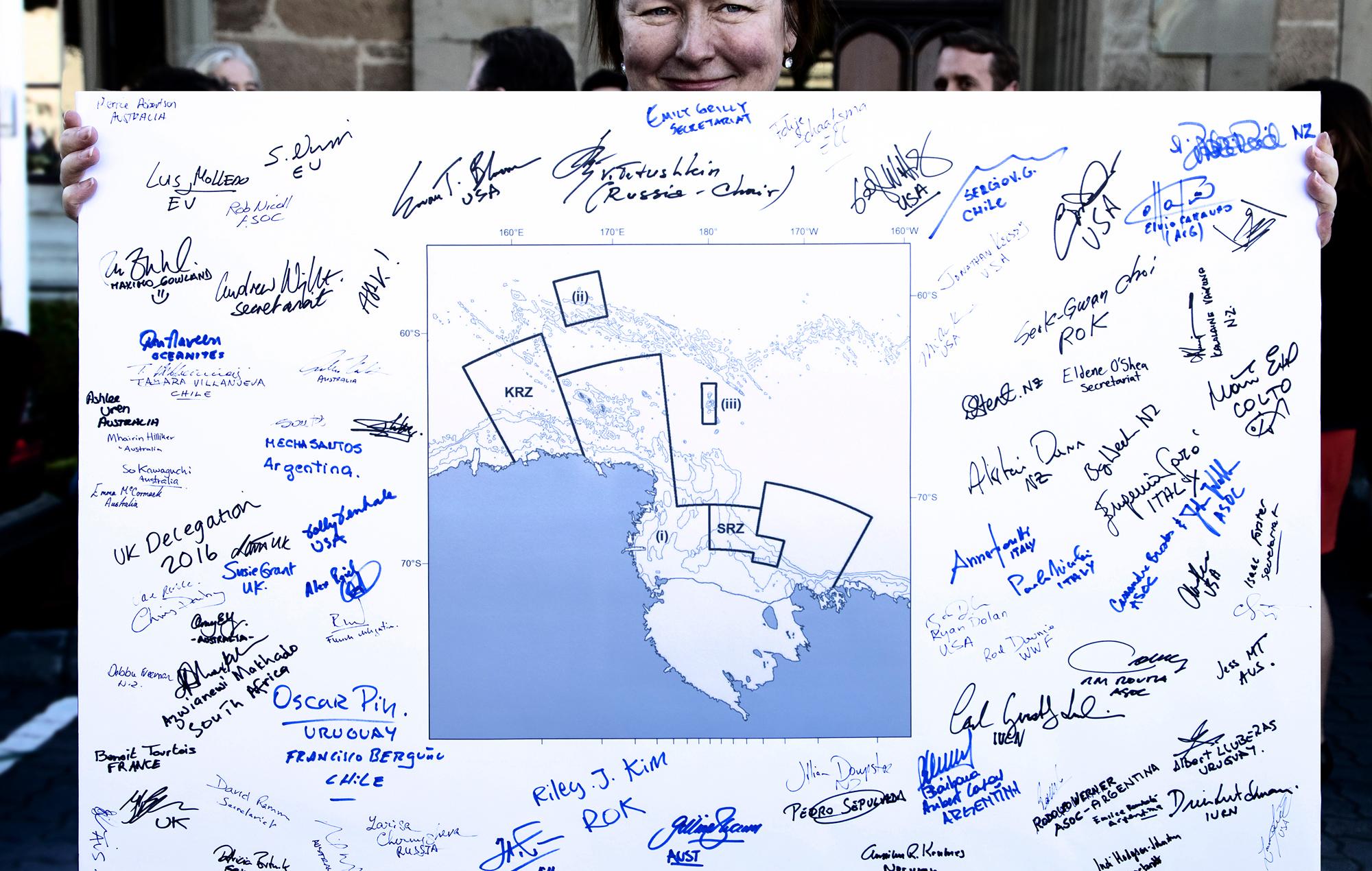

It had been a long time since I cried in public. But on October 28th, 2016, I was not the only one openly weeping in a stone fortress in the center of Hobart, Tasmania, as I witnessed 24 Nations and the European Union establish the world’s largest marine protected area in the Ross Sea, Antarctica.

I had been a professional photographer for 6 years when I first heard about the Ross Sea. The effort to protect it would consume the next 12 years of my life. It started for me in 2004 when I read a paper by Antarctic ecologist David Ainley, who outlined the story of the Ross Sea, identifying it as the last large intact marine ecosystem left on Earth. This idea—that we had but one pristine place left in the entire ocean—got under my skin. It was an itch that I couldn’t scratch, and I eventually called David. We met some weeks later and committed to work together to build a campaign for a marine protected area in the Ross Sea.

I’ll fast-forward through the years of single-minded pursuit, working alone in our respective garages, sometimes for days at a time with no sleep, as we slowly built momentum. We joined forces with New Zealand filmmaker Peter Young, and as a trio, The Last Ocean Project began to fully take shape. We helped found and build what would become a global coalition of organizations, scientists, diplomats, and eventually entrained the attention of world leaders. This pursuit brought me to the Ross Sea four times. My images became the face of Antarctic conservation efforts worldwide, published thousands of times, reaching a global audience of nearly 1 billion people. We collected 1 million signatures. I had meetings with presidents.

As we fought to bring the Ross Sea into the public view, teams of brilliant and tireless people fought concurrent battles in boardrooms and scientific journals all over the world. But then the train stalled on the tracks. For years, the vision of protecting the last pristine place seemed more and more unlikely. I fell, at times, into deep depression. And as my faith in the outcome waned, so did my faith in humanity. I lived this pursuit, and on several specific occasions, it nearly killed me.

All of that changed on an October night in the stone fortress that houses the annual meeting of the Commission for the Conservation of Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR)—the international government body that manages the Southern Ocean. Led by delegates from the US and New Zealand, the proposal for the Ross Sea Marine Protected Area was unanimously adopted. In that moment, in protecting the most pristine marine ecosystem left on Earth, CCAMLR members redefined what is possible in international collaboration. They created a blueprint for the conservation—not just for the protection of the Southern Ocean, but for our global ocean, the source of life on Earth. It was an astounding achievement. This was a gift to all of humanity,

present and future. I wish all of you reading this could have been there when the room erupted. Nations were literally hugging other nations. I can guarantee that it would have made you cry.

Today, we continue to fight for further protection of Antarctica, and other critical oceans around the globe. Follow our work and join our team at www.sealegacy.org.

© 2020 John Weller. All rights reserved.

Protecting the Southern Ocean

BFCSEC presents: The Climate and Biodiversity Crisis: Moving Toward a Global Awakening?

Scientist who ‘always undercut’ herself now wins high praise, awards

CU’s Cassandra Brooks, a core member of the Last Ocean Project—a global outreach effort to safeguard the Ross Sea, wins high praise and awards.

Colorado Arts and Sciences Magazine (October 2022)

More protections needed to safeguard biodiversity in the Southern Ocean

CU Boulder Today (April 2020)