The CU Museum is closed. We will be reopening soon.

During this time, collection visits will be available by appointment and other special access requests will be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Please email cumuseum@colorado.edu for more information.

Coprolites

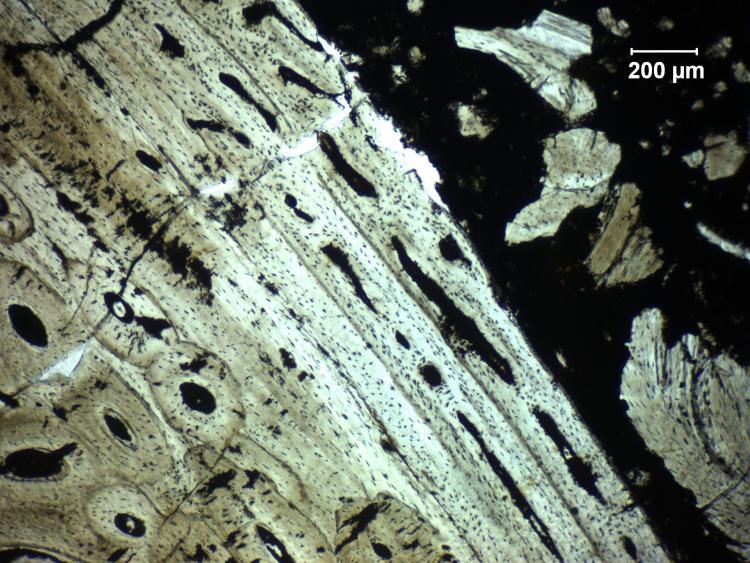

We do not know the exact identity of the defecator, but rigorous observation and comparisons suggests the feces were produced by an allosaurid dinosaur—one of the large carnivorous theropods that coexisted with even larger sauropods (brontosaurs) during the Jurassic Period (140 million years ago). This specimen is but a piece of a fecal mass that was larger (we don’t know its original size). We also cannot tell who the ‘victim’ was, but analysis of the bone within the specimen offers clues. The second photograph is of a thin section of the coprolite (an ultra-thin slice made with a diamond-bladed saw and mounted on a glass slide) taken with a microscope. The bone growth patterns indicate that the victim was an adult dinosaur.

This coprolite provides still more evidence for feeding behaviors of long ago. Some of the bone fragments in the coprolites have conspicuous boreholes in them! To tackle this mystery, we learned about modern animals that are known to bore into bone. It is quite possible that the Jurassic bone-borers were ancient dermestid (flesh-eating) beetle larvae that were preparing sites to pupate and metamorphose into adults. The bone boring occurred after the poop was deposited and not in the living animal’s bones.

Coprolites offer direct evidence of feeding activity in ancient environments. Even when we don’t know exactly which animals produced animal signs, we can learn much about ancient ecosystems (paleoecology) and processes of fossilization. After all, our museum has Dr. Karen Chin who is one of the world’s leading experts of coprolites. We plan to discover and learn more about coprolites—and we’ll share our findings with you!

If you would like to know more about Dr Chin’s work, she has been featured in the media and has authored a children’s book on this topic.

Discovering The Past Through Dino Poop

Science Friday (2018)

Dino Dung

Random House Books (2005)

Reading the Book of Life in Prehistoric Dung

Nautilus (2013)

Chin, K., and Bishop, J.R., 2007, Exploited twice: Bored bone in a theropod coprolite from the Jurassic Morrison formation of Utah, U.S.A.: Sediment-Organism Interactions: A Multifaceted Ichnology, SEPM Special Publication, no. 88, p. 379-387.