The Secret Life of Mary Rippon

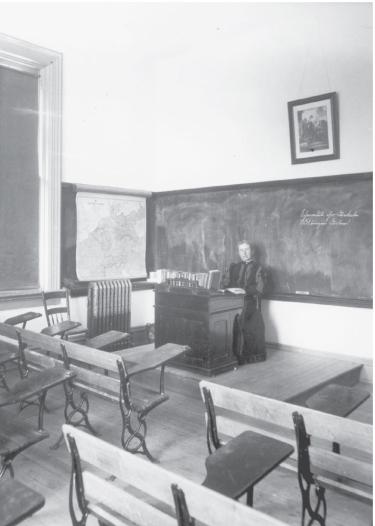

Mary Rippon in 1882.

In September 1877, the University of Colorado began its first academic year. Joseph Sewall served as the university’s president, and 55 students were enrolled. Old Main was the sole building on campus.

While looking for faculty to staff the school, Sewall sent a letter to 27-year-old Mary Rippon, whom he met while teaching at her high school, the Illinois State Normal School. He offered her a position teaching French and German language and literature.

Rippon accepted and traveled West via train. She was enamored with Colorado’s beauty, which she likened to Switzerland, where she’d traveled previously.

In January 1878, she became CU’s first female professor and was among America’s first female professors to teach at a state university. The regents offered her a salary of $1,200 a year.

For over 30 years, Rippon worked for CU, gaining respect and admiration from students, faculty and the Boulder community. When she retired in 1909 as head of the Department of Germanic Languages and Literature, the CU newspaper Silver and Gold stated, “By her untiring energy as a teacher and her lovable personality, she has brought the German Department to its present high standing and popularity, and all who knew her will be sorry to learn of her departure from the University.”

In 1936, CU dedicated the Mary Rippon Outdoor Theatre in recognition of her contributions to the university, especially in the arts and humanities. The theater remains home to the second-oldest Shakespeare Festival in the United States.

Yet, despite her revered standing at CU, there was more to Mary Rippon’s story — she lived a double life driven by a deeply personal secret.

Very few people knew Rippon’s secret while she was alive. But in 1993, Boulder historian Silvia Pettem (Psych’69) began digging into her past life to unearth the whole story.

It started when Pettem was poking around the Norlin Library archives in search of ideas for Boulder’s Daily Camera newspaper, where she worked as a columnist. A librarian presented her with intriguing information about Mary Rippon.

“I thought it would be my next article,” said Pettem. “It ended up being a five-year project.”

Rippon pictured in her CU classroom.

A Secret, Kept

In 1986, a man named Wilfred Rieder claimed to be Rippon’s grandson and donated her diaries and account books, which itemized Rippon’s financial expenses, to CU. Seeing as Rippon had always been known to be unmarried and childless, the revelations within puzzled many in the university community. The librarians hoped a researcher could delve into the works to sort out the story. Pettem was hooked.

As she began her research, Pettem learned something shocking: In spring 1888, at age 37, Rippon fell in love with a 25-year-old student, Will Housel, and became pregnant with his child. When the semester ended, the pair married privately and returned to Rippon’s home state of Illinois for the summer.

CU’s regents then approved a year-long sabbatical request from Rippon, in which she stated she hoped for time to focus on her health. No one at the university knew she was pregnant. In the fall, Housel returned to CU to complete his studies, and Rippon traveled to Germany to stay with a trusted friend. In January 1889, Rippon gave birth to their daughter, Miriam.

Pettem learned that Rippon would hide Miriam and her relationship with Housel from the public, but financially support them for the remainder of her life.

The story captivated Pettem, who decided to write Rippon’s biography.

“She was a very well-respected and well-loved professor,” said Pettem, who was influential in obtaining an honorary doctorate for Rippon, which was conferred at commencement in 2006.

“I didn’t want to tarnish her reputation in any way,” she said. “I wanted to know: Was this a tragic story? Was it a happy story? Did she like her life? Did she hate her life?”

Living a Double Life

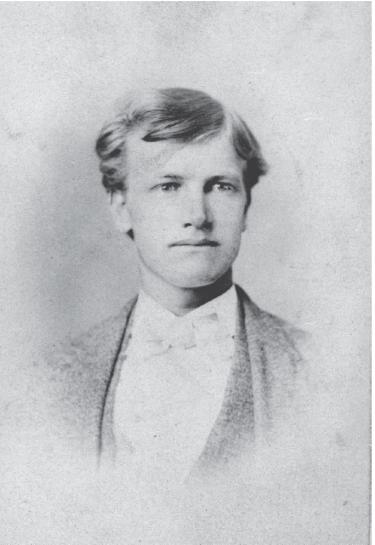

William Housel, Rippon’s former husband and father to her daughter.

Pettem’s years-long journey took her through countless artifacts and across the country to Rippon’s hometown in Illinois. She poured through newspaper articles and photographs. And she had Rippon’s own words in her hands.

“She had a real delicate handwriting with purple ink,” Pettem said.

As reported in Pettem’s biography Separate Lives: Uncovering the Hidden Family of Victorian Professor Mary Rippon (first self-published in 1999, with a second updated version released by Lyons Press in 2024), Rippon loved Boulder’s wildflowers, had great rapport with her students and was meticulous with journaling her expenses — including the ways she divided her meager university wages to support her small family.

During the Victorian era, Pettem said Rippon would have almost certainly lost her job if people had known she had a child. It was considered a woman’s duty to care for her husband and child at home, Pettem explained. Her position at the university would have been given to a man who would likely provide for a wife and children.

And so, to keep her job at the university and to care for her students (many female students referred to her as “mother”), Rippon chose a life of secrecy.

“As a writer, I couldn’t pass judgment on her. I just reported on her,” said Pettem. “I admired her determination. She did what she wanted to do.”

Supporting a Child From Afar

Pettem’s book sheds light on Rippon’s life after giving birth to Miriam.

This photo is most likely Miriam Housel, Rippon’s daughter.

Rippon spent the remainder of her sabbatical in Europe, and Housel joined her after graduating from CU. However, since Housel had no money or job, and Rippon was returning to teach at CU, the couple decided to place Miriam in a Catholic orphanage in Geneva, Switzerland, where Rippon could afford her care. Housel remained close to the orphanage while taking graduate courses at the University of Geneva, also paid for by Rippon.

When Miriam was two years old, Housel moved back to Boulder, leaving Miriam at the orphanage. Housel and Rippon saw each other twice weekly, but never publicly as husband and wife.

Two years later, Housel traveled to Europe to bring Miriam to the United States. She most likely lived in a Denver girls’ home, Pettem wrote, financially supported by Rippon, who saw her daughter only occasionally. Miriam called her “Aunt Mary,” unaware of their true relationship until Rippon told her as an adult.

Eventually, Rippon and Housel divorced. Between the secret marriage and living separately, they were unable to maintain a close relationship. Housel moved permanently to Michigan with Miriam and remarried. Rippon continued to provide money to the pair, occasionally sending funds to support Housel’s new wife and their children.

Meanwhile, Rippon lived alone at 2463 Twelfth Street in downtown Boulder, a home she’d bought after boarding with Boulder families for nearly two decades. She could walk to campus. She planted lilies of the valley in her garden. Students visited her home frequently for stimulating conversations about literature or language.

Pettem reports that in 1907, students wrote under her yearbook photo: “Earth’s noblest thing — a woman perfected.”

She appeared, Pettem said, content.

Duty or Love?

If Pettem were to meet Rippon today, there’s one thing she’d want to know first.

“I’d say: ‘I hope you don’t mind me asking this, but how did it all start with Will?’”

Rippon in 1906.

She mused that the pair could have shared a love for languages, authors or the beauty of the Colorado outdoors. (Housel had a farming background and rode to campus on a horse.)

Whatever drew them together, it created a bond that defined Rippon’s private life — forever.

But how did her dual lives affect Rippon internally?

Pettem has her ideas.

“Did she feel guilty? Possibly,” she said. “Maybe this was all out of duty ... or maybe it was love.”

While her writings were often cryptic, Rippon left one small clue to how she felt about it all in a diary entry written before she died in 1935 at the age of 85, Pettem said.

Rippon wrote: “Conventionality is the mother of dreariness.”

“I think with that statement,” Pettem said, “she felt she had lived the life she wanted to.”

Photos courtesy Carnegie Library for Local History/Museum of Boulder Collection; Mary Rippon Papers, Cou: 1353, Box 2, Folder 1, Rare and Distinctive Collections, University of Colorado Boulder Libraries; Heritage Center