The Man in the Cracker Tin

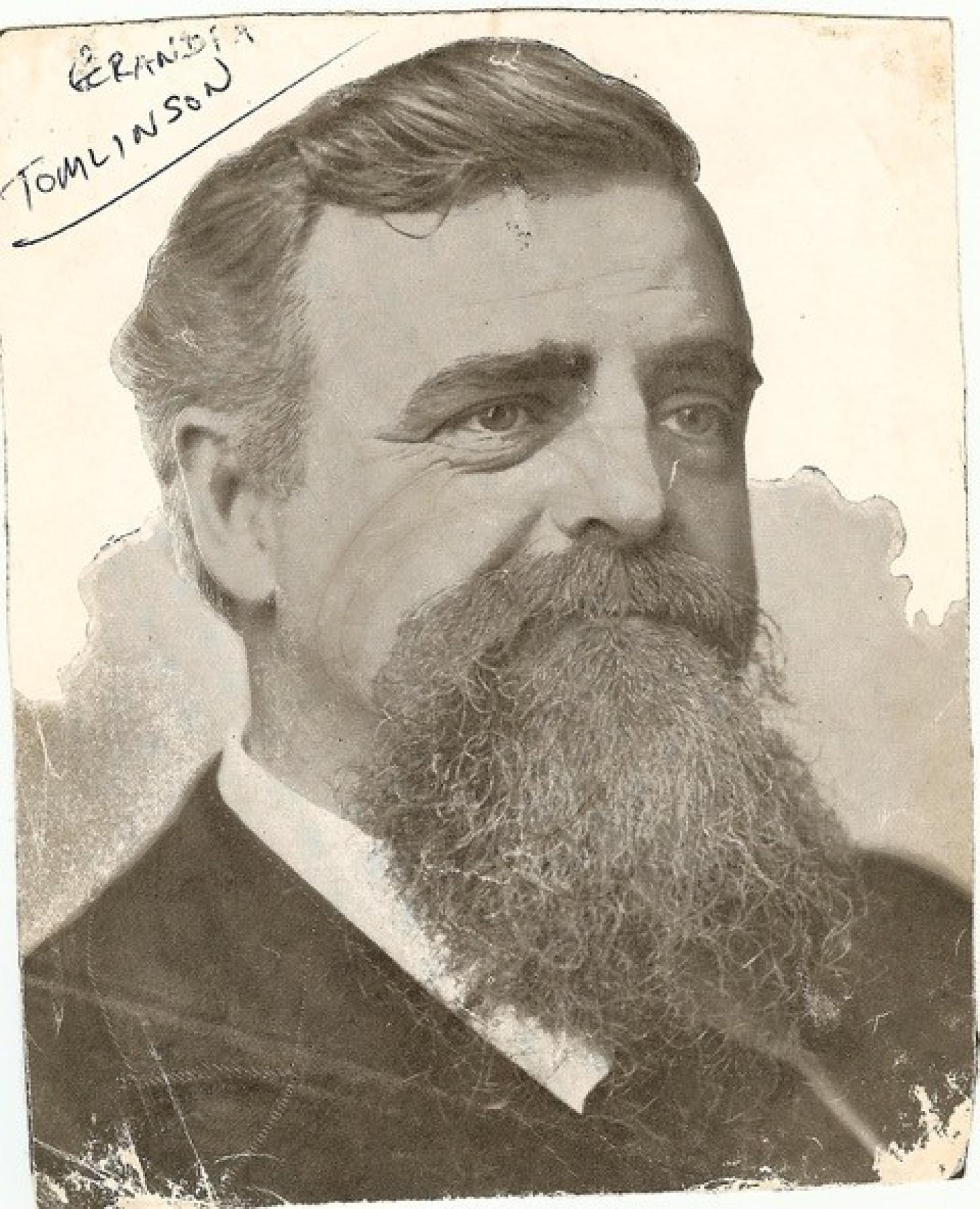

In an old cracker tin, hidden on her grandparents’ bookshelf in Portsmouth, Ohio, Pat Donohoe (MEngl’82) and her sister, Betsy Ross Donohoe (MComm’83) found the first letters. They dated to the Civil War and were in the hand of her great-great grandfather, Will Tomlinson, and other long-gone family members.

“We were just blown away in excitement,” Donohoe, now a retired minister, said of that initial discovery, back in 1970.

Over the next three decades, Pat Donohoe dug further into her family’s past, tracking down 150 additional letters on eBay that shed light not just on her family’s history, but also on America’s during its most trying era.

“I was awed reading these letters to think that they were from this time period, from people who were actually on the scene [during the Civil War],” said Donohoe, who eventually published a book, The Printer’s Kiss, the Life and Letters of a Civil War Newspaperman and His Family, reprinted last year by Kent State University Press. “Holding the same paper their hands had held and seeing their strokes of joy and agony on the page connected me to them.”

The letters gradually filled in her sketchy outline of Tomlinson, an outspoken newspaper editor she’d only heard stories about growing up.

Some were pretty colorful. In one, he defends himself to his wife, Eliza, against accusations that he entertained prostitutes while away at war in Cincinnati.

“I utterly deny that I spend either time or money with strumpets or any other kind of women,” he wrote in an 1863 letter.

Exchanges like that held Donohoe’s attention and inspired her to keep researching.

“It’s become more than a hobby, more like an obsession,” said Donohoe, a former teacher and editor.

For a while, she cast the letters aside while she went into ministry. It was not until 2004 that she was able to make time for transcribing them.

“I wasn’t getting any younger and knew that if I was going to do it, I needed to get with it,” said Donohoe, 71 and of Shepherdstown, West Va.

The letters were suspenseful and brought her closer to her ancestors and to the people of their time. She began to appreciate that they wanted the same things people still treasure today — a good home, faith, life.

“Reading the letters and the struggles they went through were both inspiring and moving,” she says. “They seem so alive and full of life that it’s hard to imagine that they lived so many years ago.”

Tomlinson, who was an editor for 10 newspapers throughout his lifetime, was known for being outspoken, against slavery and for the common man.

“He was very articulate and very clear about what he believed in,” Donohoe said. “Editors back then printed some stuff that could really get them in trouble today.”

It all came at a price: In November 1863, on the banks of the Ohio River, Tomlinson was fatally shot by a Kentucky Copperhead, a Confederate supporter. He was 40 years old.

“I would have felt terrible if I had got to the end of my life and this was something I hadn’t done,” Donohoe said of her project. “That I had broken a sacred trust, buried a gift that was meant to be shared.”