The roads net taken

Photos by Kimberly Coffin (CritMedia, StratComm’18)

Robert Frost once wrote of two roads diverging in a yellow wood, and imagining his narrator eventually regretting whichever choice he made.

“I want to introduce a sense of wonder and marvel about what has happened—and what could still be possible.

Lori Emerson

Associate Professor

Media Studies

Lori Emerson is also fascinated by the road not taken. But unlike Frost, who is looking forward down those roads, she is looking backward, to the technology-related choices—around networks, protocols and structures—that led us to this moment.

And, especially, what we can learn from the choices we didn’t make along the way.

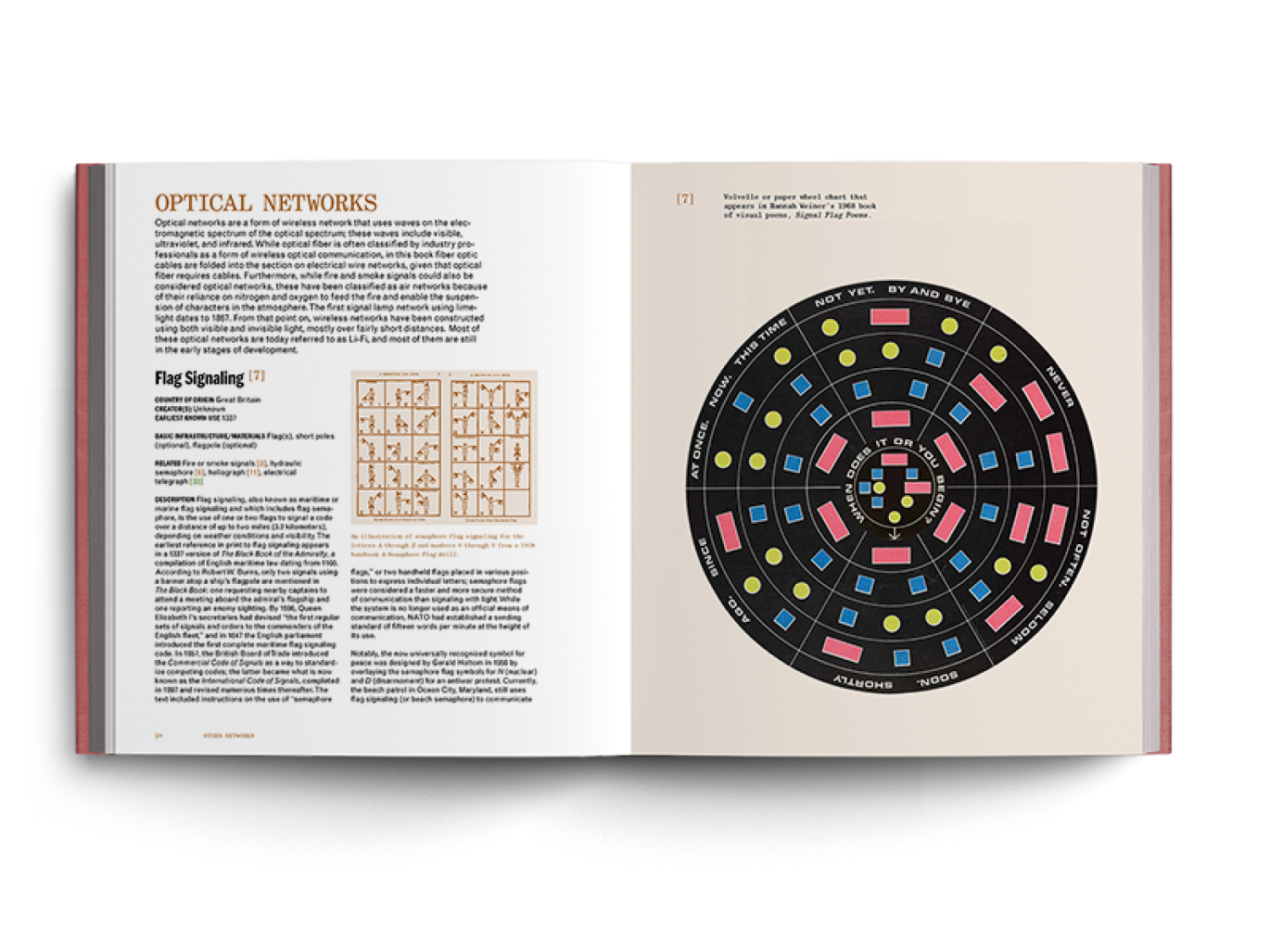

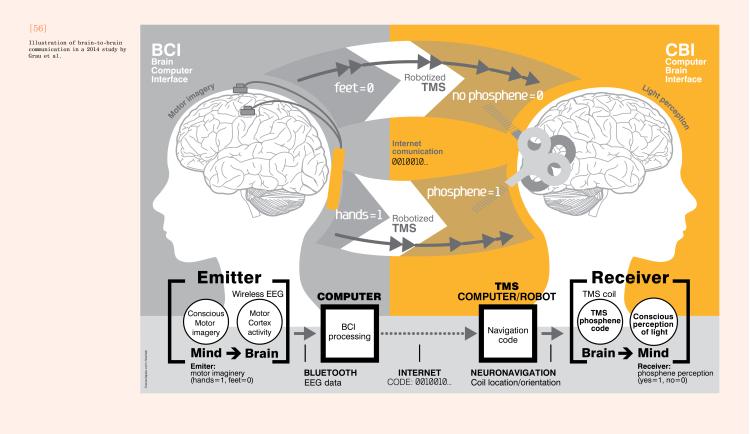

It’s something Emerson, an associate chair of media studies at CU Boulder’s College of Media, Communication and Information, explores at length in Other Networks: A Radical Technology Sourcebook, which she published last month.

“I want to introduce a sense of wonder and marvel about what has happened—and what could still be possible,” Emerson said.

It can be difficult to imagine what something like the internet might look like in an alternate timeline. But in fact, just calling it “the internet” makes it feel like the preordained platform that we were inevitably going to get.

“The internet is just a network of networks,” she said. “There are other networks of networks, and there could be others in the future. What bothers me is this unquestioned narrative about the internet as this singular endpoint—that it only could have been created in the U.S. in the way in which it currently exists.”

A quiet activist

There is a quiet strain of activism in Emerson’s work that’s getting a little louder: She’s trying to be more outspoken at a time when technology is increasingly consolidated in the hands of a few major players.

“The future feels predetermined and has left most people feeling like they have no power to intervene, and we all just have to accept things as they are,” she said. “And so what I’m trying to do is poke holes in that ideology with very simple, compelling examples from the past.”

Simple and compelling are rarely adjectives used to describe an academic publication, but Emerson leaned on her background in experimental poetry and poetics to break a few boundaries. The result is a beautifully designed book that wouldn’t seem out of place among the vintage instruction manuals created for telephones and telegraphs from generations ago.

“Women played a huge role in the creation, adoption and maintenance of networks, from the telephone to the radio, but have been erased in favor of individual white guy inventors,” she said. “I wanted to create an alternate universe in a book that echoed that history you see in those cloth, hardcover, gold-foiled instruction books—but in a way that was feminized.”

Her book isn’t the only public-facing space where Emerson offers critical thinking around technology. CMCI’s Media Archaeology Lab started as a way for Emerson, the lab’s director, to collect Apple IIe computers in order to run an experimental kinetic digital poem in class. It has evolved to become an extremely thorough repository of obsolete, but still functioning, technology, from Ataris to Zip drives.

“The more we gathered, the more I became convinced that hands-on access to historical technology is essential to understand how it actually works,” she said. “You have to be able to use it, to take it apart. By doing so, you come to appreciate how we got to the point where these technologies were created, and imagine alternative presents and futures.”

New book, old story

The book is new, but the story of technology as a linear narrative isn’t. Beyond the lab, Emerson’s work has gone as far back as how rural communities created the party-line phone system by tapping the miles of barbed-wire fence spanning their properties. That kind of alternate network—one Ma Bell didn’t control—is something she wants readers to think about while questioning the narrative Silicon Valley has put forth as the internet’s origin story.

It’s almost a book that didn’t happen. Emerson was well past her deadline before realizing she had to narrow how deep her focus would go; “a full accounting of all the networks out there would never get finished,” she said.

As it was, the manuscript tripped some wires in China—censors objected to a part discussing how activists in the Tiananmen Square massacre used faxes to communicate with one another—which meant printing had to be moved to Turkey. As the materials arrived for printing, a once-in-a-lifetime snowstorm struck, delaying production by almost a month.

Finally, her publisher declared it was going out of business after the first run of books was printed. A limited run is available, and Emerson plans to get it to a new publisher once the existing copies have sold.

“The whole thing has been one surprise after another, honestly,” Emerson said. “When you think about Chinese censorship—of course it happens, but to actually have it happen to you is something else altogether.”

She hopes readers appreciate the look and feel of her text, while maybe finding in it a reason to be hopeful about technology by re-examining its past.

“I hope people take from it a different sense of the history, and feel excited and empowered, rather than just absorbing the dominant narrative about how everything is terrible,” Emerson said.

Joe Arney covers research and general news for the college.

Photographer Kimberly Coffin graduated from CMDI in 2018 with degrees in Media Production and Strategic Communication.