Al Nakkula Award: Injustice in Juvenile Courts

Mark Harris for ProPublica

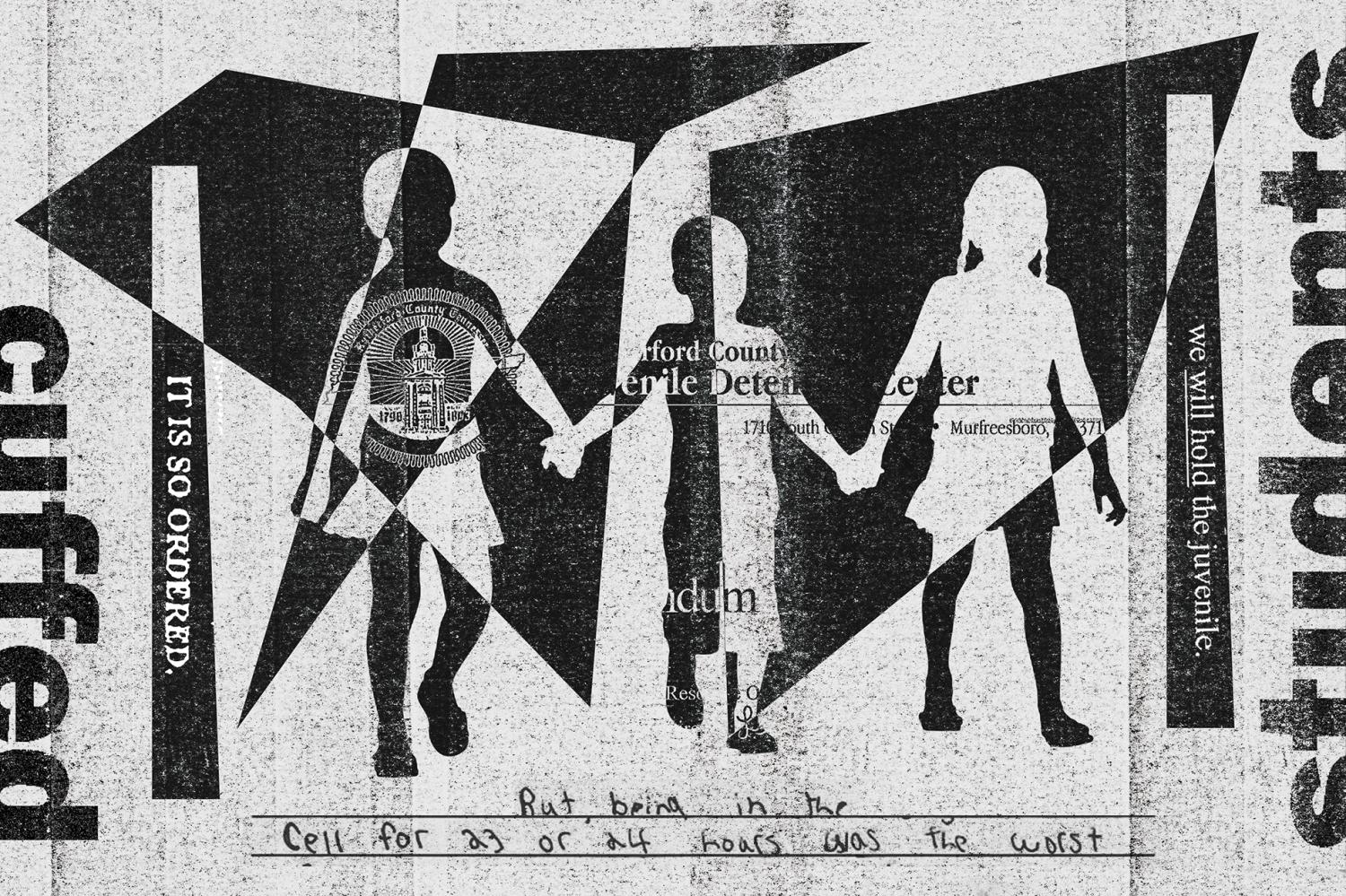

It was a sunny afternoon in 2016 when police arrived at Hobgood Elementary School in Rutherford County, Tennessee, to arrest several Black girls for watching a scuffle between young boys and not stopping it. The girls, and seven other Black children who witnessed the scuffle, were charged with “criminal responsibility for conduct of another.”

The crime, however, does not actually exist—a fact detailed in a multiyear investigation by reporters Meribah Knight of Nashville Public Radio and ProPublica’s Ken Armstrong.

Their investigation ultimately revealed a web of injustice in Rutherford County’s juvenile justice system. This year, it was chosen as the 2022 winner of the Al Nakkula Award for Police Reporting.

For more than 30 years the Al Nakkula Award, co-sponsored by The Denver Press Club and the University of Colorado Boulder’s College of Media, Communication and Information, has recognized the best journalism on crime and justice from around the country. Not only did Knight and Armstrong’s investigation reveal systemic failures, it sparked community reforms and demonstrated expert reporting on a secretive system that harmed children—qualities that distinguished it from other award entries, judges said.

“Knight’s dogged determination to discover the reasons behind the arrests of four elementary school children led to a deep dive into a system often hidden to the world,” said Chuck Plunkett, the lead judge and CU News Corps director. “Knight’s instincts and drive are reminiscent of our contest's namesake.”

The Al Nakkula Award honors the late Al Nakkula, a 46-year veteran of the Rocky Mountain News, whose tenacity made him a legendary police reporter. This year, more than 40 national media outlets submitted entries to a panel of four judges including Plunkett; Joey Bunch, a senior correspondent for The Gazette and senior writer for Colorado Politics; Nancy Lofholm, a Western Slope freelancer and contributor to The Colorado Sun; and Kevin Vaughan, an investigative reporter for 9News and president of The Denver Press Club.

Each year, judges look for stories that meet the highest journalistic standards, help readers understand complex issues and solutions, show a commitment to community, and bring about societal change.

This year’s runner-up is USA Today’s 10-part series, “Behind the Blue Wall,” which investigated consequences for police officers who speak out against police misconduct. Reported by staff writers Gina Barton, Daphne Duret and Brett Murphy, the story revealed an unofficial system of retaliation and a code of silence that hinders accountability within police forces.

"The Al Nakkula contest drew very strong entries that focused on corruption in police departments and justice systems across the country,” Lofholm said. “But [the winning] entry stood out for highlighting children who normally would not have had a voice, children caught in a web of incompetence and corruption in a system that is mostly closed off to media scrutiny.

Screenshots from a heavily filtered video, originally posted to YouTube, showing a scuffle among small children that took place off school grounds. Screenshots by ProPublica

Uncovering injustice in Rutherford County

As Knight and Armstrong investigated the arrests of the school children in Murfreesboro, a city in Rutherford County, they filed more than 50 Freedom of Information Act requests, analyzed hundreds of documents, and dug through hours of video and audio recordings.

The reporters discovered the incident at Hobgood Elementary wasn't isolated—the county had been illegally arresting and jailing children for years.

Juvenile Court Judge Donna Scott Davenport, who failed the bar exam four times, had established a norm to arrest children rather than issue a citation with a court date, the reporters found. The county also had illegal written policies, referred to as a “filter system,” for detaining children. The policies went unnoticed by state inspectors for years

Victims of false arrests brought Rutherford County to court, including a class-action lawsuit that the county settled for about $6 million. However, Davenport remained the county’s judge and indicated she would run for reelection.

In October 2021, Knight and Armstrong published their findings in a six-chapter story, “Black Children Were Jailed for a Crime That Doesn’t Exist. Almost Nothing Happened to the Adults in Charge.” The story, which ProPublica research reporter Alex Mierjeski also contributed to, was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Nashville Public Radio.

Four days after the October story was published, the president of Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro announced that Davenport, who was an adjunct instructor, would no longer be affiliated with the university, Knight and Armstrong reported.

About one week later, 11 members of Congress asked the U.S. Department of Justice to open an investigation into Rutherford County’s juvenile justice system.

In January 2022, Tennessee lawmakers introduced a bill to remove Davenport due to an abuse of power. Not long after ProPublica wrote an article about the bill, Davenport announced she would retire and would not seek reelection.

"Through solid and startling reporting, Knight's collaborative team affected changes in the Murfreesboro juvenile justice system,” Lofholm said. “Those changes are ongoing and likely are prompting other juvenile systems in the country to examine their own practices.”

Following Knight and Armstrong’s initial story, readers began asking if racial disparities were evident in Rutherford County.

The reporters investigated further and worked with ProPublica’s deputy data editor Hannah Fresques. They discovered the county jailed Black children at a disproportionately higher rate, and the disparity was worsening.

“The juvenile justice system in many states operates in near-total secrecy, and reporters Meribah Knight and Ken Armstrong exposed what can happen when no one is looking,” Vaughan said. “This kind of accountability reporting is vital—and in a crowded field of exceptional work, it was simply the best of the best.”

Knight and Armstrong’s investigative series has been read more than 3.5 million times. Recently, it was also named a finalist for the 2022 Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting.

"Nashville Public Radio and ProPublica revealed and exposed what most police reporting misses: Bad cops aren't the sole cause of society's most neglected injustices,” Bunch said. “Here, Meribah Knight and Ken Armstrong went beyond the badges and bars to a broken system that breaks kids.”

The first place award will be presented to Knight and Armstrong during The Denver Press Club’sDamon Runyon Award ceremony April 22.

Tayler Shaw graduated from CMDI and the College of Arts and Sciences with degrees in journalism and Spanish in 2021.