Divine intersection

The convergence of media, religion and culture gains momentum in the digital age

Look back just a few decades, and religious themes in the popular media were few and far between.

In 1956, Cecil B. DeMille broke box office records with his Biblical blockbuster The Ten Commandments.

In the 1970s, Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker became household names by introducing televangelism to the masses.

In the 1980s, Madonna drew intense fire from the Vatican for wearing crucifixes alongside lacy lingerie and dedicating her song “Papa Don’t Preach” to the pope himself.

Religion remained a sacred subject relegated mostly to ancient texts and pews. Even journalists steered clear of it. But today, times have changed, says Stewart Hoover, founder of CMCI’s Center for Media, Religion and Culture (CMRC).

“There are Bible apps and confession apps, virtual pilgrimages to Buddhist temples online, and a whole host of TV shows and movies,” he says. “Religion has been diffused into the public space in ways it has never been before.”

With that in mind, the 12-year-old center—one of just three like it in the country—is boosting its efforts to provide education, scholarship and conversation around the intersection of media, religion and culture.

Funded by a $500,000 grant from the Henry Luce Foundation, the center recently launched a Public Religion and Public Scholarship in the Digital Age Project, assembling a dozen top international scholars to collaborate on research, develop video documentaries and create teaching materials for the still-nascent field.

In August, the center hosted the 11th annual International Society for Media, Religion and Culture conference, drawing hundreds of attendees for public panels on everything from “Teaching Religion and Journalism in the Age of Trump,” to the role of podcasting in the Mormon and Buddhist faiths, to the way Islam is portrayed in movies.

Meanwhile, Hoover’s undergraduate Media and Religion class gets larger every year. And the center’s yearlong, weekly graduate seminar now draws doctoral students from around the globe, a testament to the center’s reputation as a pioneer in the field.

“As responsible citizens in a plural democracy, we have an obligation to become open-minded and informed about various faiths and other spiritual experiences,” says Nabil Echchaibi, associate professor of media studies and co-director of the center. “CMRC is ideally positioned to engage various publics, beyond academic echo chambers, in these conversations.”

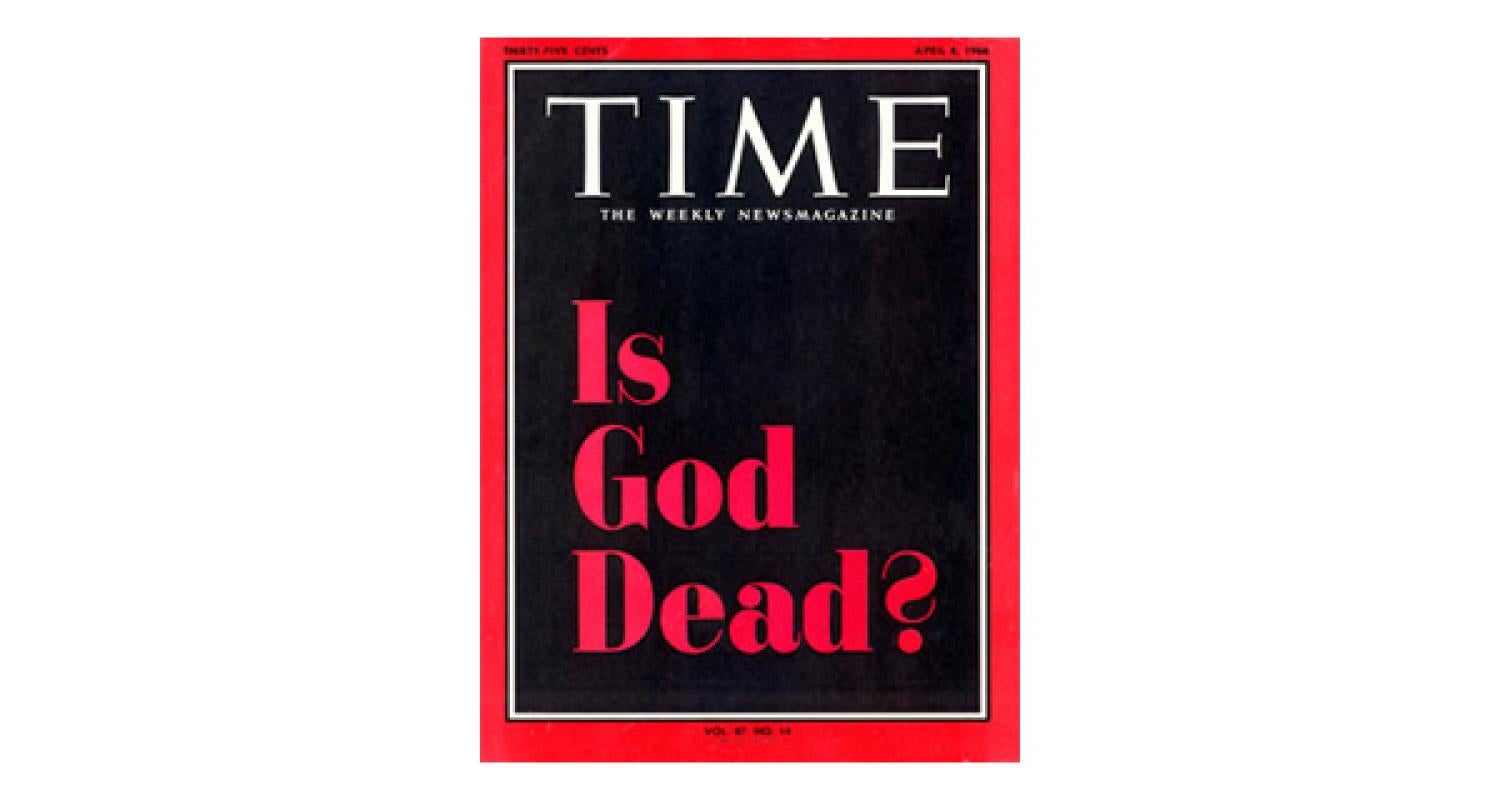

God is not dead, after all

Hoover recalls that when he was in graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania, the United States was trending secular.

“It was assumed at the time that religion was fading away and we, as scholars, didn’t need to pay as much attention to it. That has clearly not been the case.”

In the aftermath of 9/11, interest in and coverage of world religions in the news media grew. And while there has been a decline in some institutionalized religious practices—such as attending worship services—many people still report having a strong spiritual life. Nine in 10 believe in a “higher power,” 56 percent believe in God, and 27 percent describe themselves as “spiritual but not religious,” up eight percentage points from five years ago, according to the Pew Research Center.

“Digital media has allowed people to articulate their religion in new ways,” Hoover says, noting that instead of going to a mosque, Muslims can use a digital prayer mat that recites daily prayers from the Koran. Can’t make it to confession? There’s an app for that.

Good or bad, the advent of new media technologies has also allowed extreme religious groups that had only a small audience to easily extend their reach.

And some religious leaders have complained that new technologies have diminished the community aspect of faith and the authority of clerical leaders.

“It used to be that your religious identity was something you got physically through your location, your church, your community,” Hoover says. “Now it is something you can make yourself online.”

The convergence of religion and politics[close-margin /]

At a time when communities are becoming more spiritually diverse and the intersection between religion and politics is increasingly the subject of public debate—the Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission case; President Donald Trump’s executive order promoting “free speech and religious liberty”—it’s more important than ever for communicators to be educated on religious matters, say Hoover and Echchaibi.

Yet, for many students, the subject remains taboo.

“People try not to talk about it,” says Erin Baptiste, an advertising major and history minor who took Hoover’s Media and Religion course last spring. She said the class made her realize how a basic understanding of religions can help communicators—from journalists to advertisers—avoid miscommunications and misperceptions. “Being able to sit down and have these discussions in an open way was eye-opening. It made us less afraid to bring it up.”

With matters of faith infiltrating everything from our Facebook feeds to our favorite movies, educating the general public is also important.

“A lot of people don’t recognize that even if they were raised atheist or they are a nonbeliever, religion is so deeply embedded in our culture that it influences them,” says media and religion PhD student Ashley Campbell. Her podcast, Holy Media, explores the places—from horror films to the presidential inauguration—where religion is hiding in plain sight.

Hoover and Echchaibi say students exposed to the center walk away with a unique skill set that can help them advise faith groups trying to navigate the changing media landscape, or report on the subject with more authority. It also opens the door for them to experience film, music, theater, dance and popular culture via a new lens.

“This thing called religion is going to be a more powerful and influential force in our culture and media in the coming decades,” Hoover says. “It is not going away, so it’s important for us all to try to understand it.”

Echchaibi agrees: “Religion remains intimately wrapped up in our daily life, our politics and our popular culture. If you have any doubts, just look at how faith was central in the Masterpiece Cakeshop case, how religious beliefs are often invoked in our immigration policy, and how Colin Kaepernick’s protest and philanthropy are deeply animated by his spiritual convictions. Simply look at his tattoos.”

Lisa Marshall graduated from the College of Arts and Sciences with degrees in Journalism and Political Science in 1994.

1956

The Ten Commandments

1966

Time magazine cover: Is God Dead?

1974

Jim & Tammy Faye Bakker: The PTL Club

1986

Madonna's tour

2009

Avatar

2011

The Book of Mormon

2011

Confession app