Poll-arized

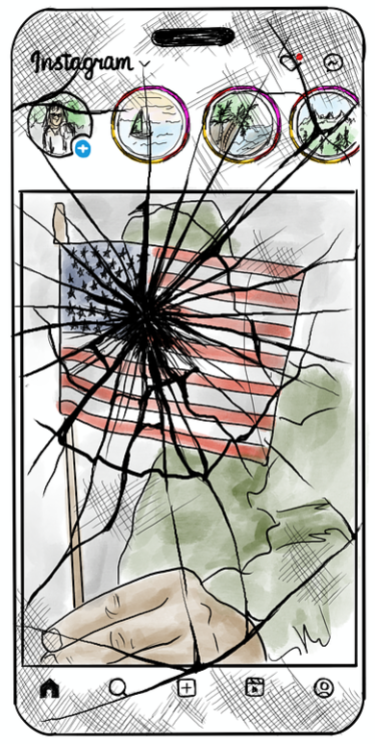

Deepfakes. Distrust. Data manipulation. Is it any wonder American democracy feels like it has reached such a dangerous tipping point?

As our public squares have emptied of reasoned discussion, and our social media feeds have filled with vitriol, viciousness and villainy, we’ve found ourselves increasingly isolated and unable to escape our echo chambers. And while it’s easy to blame social media, adtech platforms or the news, it’s the way these forces overlap and feed off each other that’s put us in this mess.

It’s an important problem to confront as we close in on a consequential election, but the issue is bigger than just what happens this November, or whether you identify with one party or another. Fortunately, the College of Media, Communication and Information was designed for just these kinds of challenges, where a multidisciplinary approach is needed to frame, address and solve increasingly complex problems.

“Democracy is not just about what happens in this election,” said Nathan Schneider, an assistant professor of media studies and an expert in the design and governance of the internet. “It’s a much longer story, and through all the threats we’ve seen, I’ve taken hope from focusing my attention on advancing democracy, rather than just defending it.”

We spoke to Schneider and other CMCI experts in journalism, information science, media studies, advertising and communication to understand the scope of the challenges. And we asked one big question of each in order to help us make sense of this moment in history, understand how we got here and—maybe—find some faith in the future.

***

Newsrooms have been decimated. The younger generation doesn’t closely follow the news. Attention spans have withered in the TikTok age. Can we count on journalism to serve its Fourth Estate function and deliver fair, accurate coverage of the election?

Mike McDevitt, a former editorial writer and reporter, isn’t convinced the press has learned its lessons from the 2016 cycle, when outlets chased ratings and the appearance of impartiality over a commitment to craft that might have painted more accurate portraits of both candidates. High-quality reporting, he said, may mean less focus on finding scoops and more time sharing resources to chase impactful stories.

How can journalism be better?

“A lot of journalists might disagree with me, but I think news media should be less competitive among each other and find ways to collaborate, especially with the industry gutted. And the news can’t lose sight of what’s important by chasing clickable stories. Covering chaos and conflict is tempting, but journalism’s interests in this respect do not always align with the security of democracy. While threats to democracy are real, amplifying chaos is not how news media should operate during an era of democratic backsliding.”

***

After the 2016 election, Brian C. Keegan was searching for ways to use his interests in the computer and social sciences in service of democracy. That’s driven his expertise in public-interest data science—how to make closed data more accessible to voters, journalists, activists and researchers. He looks at how campaigns can more effectively engage voters, understand important issues and form policies that address community needs.

The U.S. news media has blood on its hands from 2016. It will go down as one of the worst moments in the history of American journalism.”

Mike McDevitt

Professor, journalism

You’ve called the 2012 election an “end of history” moment. Can you explain that in the context of what’s happening in 2024?

“In 2012, we were coming out of the Arab Spring, and everyone was optimistic about social media. The idea that it could be a tool for bots and state information operations to influence elections would have seemed like science fiction. Twelve years later, we’ve finally learned these platforms are not neutral, have real risk and can be manipulated. And now, two years into the large language model moment, people are saying these are just neutral tools that can only be a force for good. That argument is already falling apart.

I think 2024 will be the first, and last,

A.I. election.”

Brian C. Keegan

Assistant professor, information science

“You could actually roll the clock back even further, to the 1960s and ’70s, when people were thinking about Silent Spring and Unsafe at Any Speed, and recognizing there are all these environmental, regulatory, economic and social things all connected through this lens of the environment. Like any computing system, when it comes to data, if you have garbage in, you get garbage out. The bias and misinformation we put into these A.I. systems are polluting our information ecosystem in ways that journalists, activists, researchers and others aren’t equipped to handle.”

***

One of Angie Chuang’s last news jobs was covering race and ethnicity for The Oregonian. In the early 2000s, it wasn’t always easy to find answers to questions about race in a mostly white newsroom. Conferences like those put on by the Asian American Journalists Association “were times of revitalization for me,” she said.

When this year’s conference of the National Association of Black Journalists was disrupted by racist attacks against Kamala Harris, Chuang’s first thoughts were for the attendees who lost the opportunity to learn from one another and find the support she did as a cub reporter.

“What’s lost in this discussion is the entire event shifted to this focus on Donald Trump and the internal conflict in the organization, and I’m certain that as a result, journalists and students who went lost out on some of that solidarity,” she said. And it fits a larger pattern of outspoken newsmakers inserting themselves into the news to claim the spotlight.

How can journalism avoid being hijacked by the people it covers?

“It comes down to context. We need to train reporters to take a breath and not just focus on being the first out there. And I know that’s really hard, because the rewards for being first and getting those clicks ahead of the crowd are well established.”

“I can’t blame the reporters who feel these moments are worth covering, because I feel as conflicted as they do.

Angie Chuang

Associate professor, journalism

***

Agenda setting—the concept that we take our cues of what’s important from the news—is as old an idea as mass media itself, but Chris Vargo is drawing interesting conclusions from studying the practice in the digital age. Worth watching, he and other CMCI researchers said, are countermedia entities, which undermine the depictions of reality found in the mainstream press through hyper-partisan content and the use of mis- and disinformation.

How did we get into these silos, and how do we get out?

“The absence of traditional gatekeepers has helped people create identities around the issues they choose to believe in. Real-world cues do tell us a little about what we find important—a lot of people had to get COVID to know it was bad—but we now choose media in order to form a community. The ability to self-select what you want to listen to and believe in is a terrifying story, because selecting media based on what makes us feel most comfortable, that tells us what we want to hear, flies in the face of actual news reporting and journalistic integrity.”

“I do worry about our institutions. I don’t like that a majority of Americans don’t trust CNN.

Chris Vargo

Associate professor, advertising,

public relations and media design

***

Her research into deepfakes has validated what Sandra Ristovska has known for a long time: For as long as we’ve had visual technologies, we’ve had the ability to manipulate them.

Seeing pornographic images of Taylor Swift on social media or getting robocalls from Joe Biden telling voters to stay home—content created by generative artificial intelligence—is a reminder that the scale of the problem is unprecedented. But Ristovska’s work has found examples of fake photos from the dawn of the 20th century supposedly showing, for example, damage from catastrophic tornadoes that never happened.

Ristovska grew up amid the Yugoslav Wars; her interest in becoming a documentary filmmaker was in part shaped by seeing how photos and videos from the brutal fighting and genocide were manipulated for political and legal means. It taught her to be a skeptic when it comes to what she sees shared online.

“So, you see the Taylor Swift video—it seems out of character for her public persona. Or the president—why would he say something like that?” she said. “Instead of just hitting the share button, we should train ourselves to go online and fact check it—to be more engaged.”

Even when we believe something is fake, if it aligns with our worldview, we are likely to accept it as reality. Knowing that, how do we combat deepfakes?

“We need to go old school. We’ve lost sight of the collective good, and you solve that by building opportunities to come together as communities and have discussions. We’re gentler and more tolerant of each other when we’re face-to-face. This has always been true, but it’s becoming even more true today, because we have more incentives to be isolated than ever.”

***

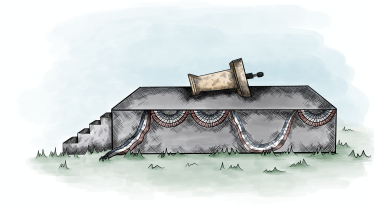

Early scholarly works waxed poetic on the internet’s potential, through its ability to connect people and share information, to defeat autocracy. But, Nathan Schneider has argued, the internet is actually organized as a series of little autocracies—where users are subject to the whims of moderators and whoever owns the servers—effectively meaning you must work against the defaults to be truly democratic. He suggests living with these systems is contributing to the global rise of authoritarianism. In a new book, Governable Spaces, Schneider calls for redesigning social media with everyday democracy in mind.

If the internet enables autocracy, what can we do to fix it?

“We could design our networks for collective ownership, rather than the assumption that every service is a top-down fiefdom. And we could think about democracy as a tool for solving problems, like conflict among users. Polarizing outcomes, like so-called cancel culture, emerge because people don’t have better options for addressing harm. A democratic society needs public squares designed for democratic processes and practices.”

***

It may be derided as dull, but the public meeting is a bedrock of American democracy. It has also changed drastically as fringe groups have seized these spaces to give misinformation a megaphone, ban books and take up other undemocratic causes. Leah Sprain researches how specific communication practices facilitate and inhibit democratic action. She works as a facilitator with several groups, including the League of Women Voters and Restore the Balance, to ensure events like candidate forums embrace difficult issues while remaining nonpartisan.

What’s a story we’re not telling about voters ahead of the election?

“We should be looking more at college towns, because town-gown divides are real and long-standing. There’s a politics of resentment even in a place like Boulder, where you have people who say, ‘We know so much about these issues, we shouldn’t let students vote on them’—to the point where providing pizza to encourage voter turnout becomes this major controversy. Giving young people access to be involved, making them feel empowered to make a difference and be heard—these are good things.”

***

Toby Hopp studies the news media and digital content providers with an eye to how our interactions with media shape conversations in the public sphere. Much of that is changing as trust and engagement with mainstream news sources declines. He’s studied whether showing critical-thinking prompts alongside shared posts—requiring users to consider the messages as well as the structure of the platform itself—may be better than relying on top-down content moderation from tech companies.

Ultimately, the existing business model of the big social media companies—packaging users to be sold to advertisers—may be the most limiting feature when it comes to reform. Hopp said he doubts a business the size of Meta can pivot from its model.

How does social media rehabilitate itself to become more trusted? Can it?

“Social media platforms are driven by monopolistic impulses, and there’s not a lot of effort put into changing established strategies when you’re the only business in town. The development of new platforms might offer a wider breadth of platform choice—which might limit the spread of misinformation on a Facebook or Twitter due to the diminished reach of any single platform.”

***

Images have always required us to be more engaged. Now, with the speed of disinformation, we need to do a little more work.”

Sandra Ristovska

Assistant professor, media studies

CU News Corps was created to simulate a real-world newsroom that allows journalism students to do the kind of long-form, investigative pieces that are in such short supply at a time of social media hot takes and pundits trading talking points.

“I thought we should design the course you’d most want to take if you were a journalism major,” said Chuck Plunkett, director of the capstone course and an experienced reporter. Having a mandate to do investigative journalism “means we can challenge our students to dig in and do meaningful work, to expose them to other kinds of people or ideas that aren’t on their radar.”

Over the course of a semester, the students work under the guidance of reporters and editors at partner media companies to produce long-form multimedia stories that are shared on the News Corps website and, often, are picked up by those same publications, giving the students invaluable clips for their job searches while supporting resource-strapped newsrooms.

With the news business facing such a challenging future, both economically and politically, why should students study journalism?

“Even before the great contraction of news, the figure I had in my mind was five years after students graduate, maybe 25 percent of them were still in professional newsrooms. But journalism is a tremendous major because you learn to think critically, research deeply and efficiently, interact with other people, process enormous amounts of information, and have excellent communication skills. Every profession needs people with those skills.”

Joe Arney covers research and general news for the college.