Video Revolution

Assistant Professor Sandra Ristovska (far left) films the short documentary Filmmaking for Democracy in Myanmar, for which she was the cinematographer.

With smartphones and social media fueling a new era of video activism, Sandra Ristovska says it’s time we give images their due respect.

By Lisa Marshall (Jour, PolSci’94)

“A picture is worth a thousand words.” A New York editor coined the phrase in 1911.

But only recently—with the rise of smartphone cameras, social media and citizen journalists who deploy them to expose human rights violations—have we begun to recognize the full potential of images, says media studies Assistant Professor Sandra Ristovska.

“Images have always mattered, but they have traditionally been treated as a sort of illustration on the side—an afterthought,” she says. “Today, they are finally being recognized as a valuable mode of information on their own, whether in court or journalism. Because of that, we need to take them more seriously.”

Born in Macedonia in the 1980s and shaped early on by images of the breakup of Yugoslavia, the filmmaker and media scholar has dedicated her career to exploring the intersection of visual images and human rights.

In recent years, eyewitness videos have exposed everything from police brutality in the United States to chemical weapons attacks in Syria. They’ve ignited race riots, swayed international policy and helped to jail perpetrators of genocide. They have also been co-opted by terrorist groups, misused by news organizations, and faked, Ristovska notes.

She’s working with activists, human rights courts, media organizations and future journalists to raise the bar on how images, particularly videos, are vetted and presented.

“We have this very powerful tool in our evidence toolbox now,” Ristovska says. “But it’s a bit of a Wild West out there.”

Telling the untold stories

Ristovska clearly remembers sitting in front of the TV at her home in Macedonia’s capital, Skopje, watching as morning cartoons were interrupted by footage of war in nearby Bosnia and Croatia.

“I remember images of refugees fleeing and hospitals being bombed. It sticks with you.”

She also remembers her mom’s friends baking pies during the NATO bombing of Serbia, 45 minutes from her home. “People learn how to live under these circumstances. To me that was an untold story.”

To tell it, she made her way to film school in London and Kansas, and spent her early career making documentaries in Macedonia, Myanmar and elsewhere.

During graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania, she began reading about the history of images in human rights activism and noticed a disheartening trend.

Although print journalists took pains to assure accuracy, the same care was not taken with images.

Holocaust photos were routinely mislabeled. The first photojournalism program wasn’t launched until 1946. And it wasn’t until the1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy that people began to view TV as a legitimate news source.

Then, in 1991, a man holding a camcorder captured footage of four Los Angeles police officers savagely beating 25-year-old Rodney King. Millions of viewers at home soon saw the footage on TV.

A new era of video activism was born.

Images can reveal but they can also conceal. We have to learn how to live with that and not necessarily demand more from them than they can give.”

The power of video

For research, Ristovska has watched hundreds of hours of hard-to-witness footage. One video has stuck with her.

It’s July 1995 in Srebrenica, Bosnia, where Bosnian Serbs killed 8,000 Bosnian Muslims that summer.

The grainy footage shows an armed paramilitary group forcing young men out of a truck and onto the ground. One young man looks back and quietly pleads: “But, sir. Please, sir. Please.”

Then the boys are marched into the woods and shot in the back.

“It’s chilling to not only see these men in this horrible situation but also hear those words,” she says. “A photo couldn’t do that.”

The video served as evidence in the trial of Serbian President Slobodan Milošević and was aired internationally, spreading word of the genocide.

Today, with such footage more accessible via smartphones, groups like WITNESS and Human Rights Watch actively train people to film in a way that will have the most impact in the media or courtroom.

But with this revolution has come a challenge: How does one assure the video is what it says it is?

“Whether it is TV satire or Netflix films, we are always responding to images and looking to them to tell us about the world. But the news does the least good job at engaging with those images responsibly,” says Barbie Zelizer, director of the Center for Media at Risk. “That is the dilemma, and Sandra’s work targets it spot on. She is fearless.”

Through her books, Visual Imagery and Human Rights Practice and Seeing Human Rights: Video Activism as a Proxy Profession, Ristovska argues that news organizations and courts need to do more to verify accuracy (cross-checking against satellite imagery, street views or geotagged photos), give credit to those who shot them and not overstate their meaning.

She tells her students the same thing: “Images can reveal but they can also conceal. We have to learn how to live with that and not necessarily demand more from them than they can give.”

1888

The Kodak camera was unveiled. Missionaries quickly used it to expose “crimes against humanity”—a term they coined—in the Belgian Congo.

1945

Photos of prisoners in concentration camps alerted the world to the Holocaust, but they often lacked captions or were mislabeled.

1948

The United Nations General Assembly drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. A year later, UNESCO organized a traveling Human Rights Exhibition of photos.

1991

The Rodney King beating launched a new era of video-driven human rights activism.

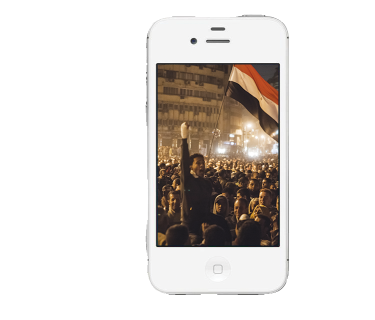

2011

The Arab Uprising: Egyptian activists take to the streets, filming with their smartphones and broadcasting video internationally via social media.

2017

The International Criminal Court issues an arrest warrant for an alleged military commander in Libya based solely on social media video evidence.

2018

Eyewitness video shows hospitalized children being treated after a chemical weapons attack in Syria.

Filmmaker Jordan Peele releases a fake video of former President Barack Obama making a speech. It turns out to be a public service announcement warning that videos can be manipulated.

Lisa Marshall graduated from the College of Arts and Sciences with a degrees in Journalism and Political Science in 1994.