Distinguished biologist advocates graduate-school reforms

Min Han talks about being named a Distinguished Professor, the qualities seen in the best scientists, and the benefit of independent thought

Min Han knows that science can be very rewarding, but he wants prospective scientists to know that they really have to love the process of research, even when good results are elusive.

He is one of seven faculty members in the University of Colorado system to be named a Distinguished Professor this year.

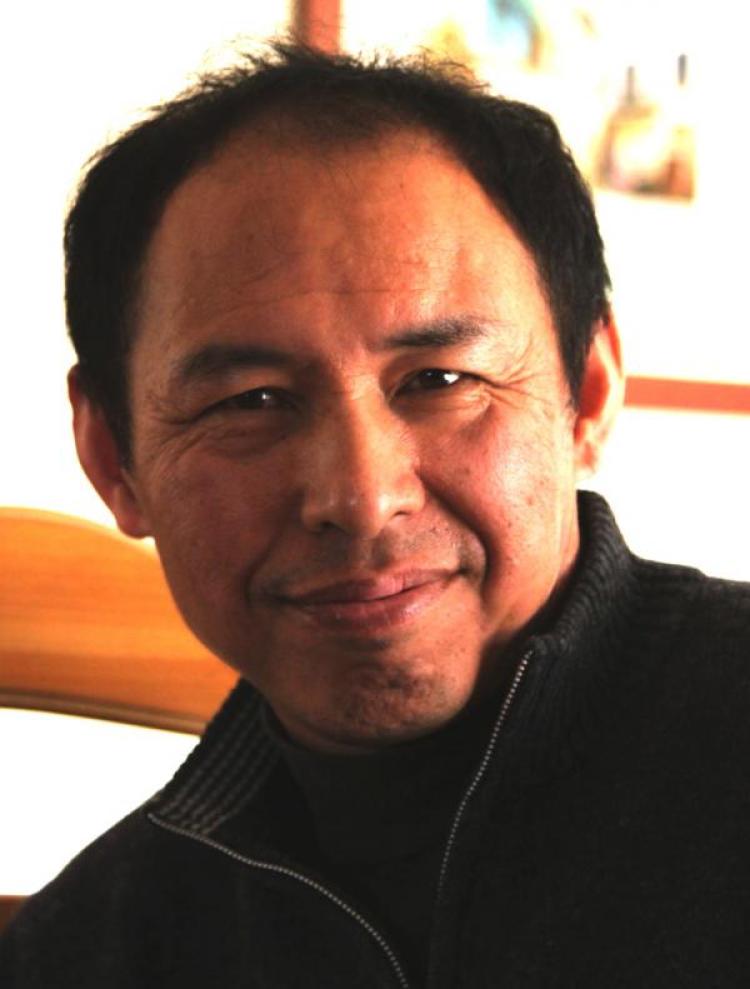

Min Han. At the top of the page is an image of E. coli, courtesy of NIH.

Today, the CU Board of Regents bestowed this honor on Han and three other members of the CU Boulder faculty: Carole Newlands of classics, Mark Serreze of geography, and David Korevaar of music.

At CU Boulder since 1991, Han has distinguished himself as a national and international authority in molecular and developmental biology.

He has run a highly dynamic research program in his lab, addressing cutting-edge problems in diverse biological fields related to human health.

He has developed and taught many courses within MCDB while also actively participating in international educational efforts.

His impact as a mentor and teacher also is noteworthy, as many former trainees have advanced to significant careers in higher education and industry.

He recently fielded five questions about his research and life, and these are his answers:

As you know, the title “distinguished professor” is an honor that recognizes distinguished scholarship, excellent teaching and outstanding teaching and service; what reaction do you have to receiving this honor?

I was very excited when I received the phone call from the president and felt so honored by the recognition. Here are a few specific thoughts:

I am very grateful to my colleagues at MCDB who nominated and presented the case on my behalf, and my colleagues outside of the university and my former trainees for the support, and the university committee for the recognition.

Because my research program has a somewhat unusual style, I was always unsure about how others may have perceived it. This honor made me feel very good about what we have done.

I am one of a large number of China-born and educated (went to college in China) professors at CU and I am likely the first one hired by CU in 1991. While we have been trying hard to learn the system and do our best in this profession, many do have extra pressure and concerns for various reasons related to the differences in our backgrounds.

I realized that this honor may have a very positive impact on this group of faculty members, particularly since I have been involved in research/education interactions between academic institutions in China and CU in the past.

Although I feel good about our contributions in research and my record in training future scientists/educators, my teaching and service may not be considered to be exceptional at CU. This honor will encourage me to do more in these regards in future years.

If you were to briefly tell an audience of high-school students why they should study molecular biology, what would you say?

This is a complicated issue that I have thought about for a long time and discussed with a huge number of early-stage graduate students (not high-school students) over the past 15 years.

Being a scientist is absolutely wonderful, but only if you enjoy the process of doing scientific research, regardless of whether you achieve the goal (results) from your efforts."

The answer is not so simple as to use the fascinating new findings in biology as the bait to lure young students into the field. My main message today would be this: being a scientist is absolutely wonderful, but only if you enjoy the process of doing scientific research, regardless of whether you achieve the goal (results) from your efforts.

I also believe that graduate programs in many places in the world, including in the U.S., need some reform; this system is not really attractive to intelligent students (also see below).

Last year, your research group published the results of a study indicating that E. coli is beneficial for humans, a finding that might be surprising to non-biologists. Was it surprising to you?

Before we made the finding, we knew very little about this particular field so the “surprise” was really based on our reading the literature to recognize that this finding was contrary to the prevailing paradigm regarding this well-known iron-binding molecule made by bacteria.

In my lab, we actually always chase the “surprising” effects (making novel discoveries) in our research. Over the past 28 years at CU, we changed research direction or field every few years (highly unusual) to give us a chance to make paradigm-shifting discoveries.

For many years, I could not even find any new students/postdoc to work on “old” problems in the lab; they all wanted to do new genetic screens to make new findings.

I also let postdocs take the projects with them to their own labs, which has also forced us to move into new areas. The finding made last year was totally the idea and work by a postdoc who only wanted to work on a new problem.

In 2015, I actually wrote an article to describe how we chose research subjects and ended up working in the lipid field that was totally foreign to us. I guess I was also influenced by my experience as a graduate student (UCLA) and postdoc (Caltech), where I also made “surprising” or breakthrough findings in new biology frontiers (epigenetics and developmental biology, respectively) at the time.

The National Academy of Sciences has expressed concern that several factors are limiting the ability of labs like yours to attract enough talented graduate students and post-docs; is this also a concern of yours, and, if so, do you have any observations about the topic?

I have a serious concern about graduate school in certain areas of molecular biology in general. As I mentioned above, the current system is not friendly to students:

The key problem is that the duration of graduate school is getting longer and longer, while the training received by the students may be arguably less, particularly in the area of training to be an independent thinker.

The funding mechanisms, faculty evaluation systems, hardship in publication and the collaborative nature of many “big science” projects, and others, while all exist for understandable reasons, may all present obstacles for the proper training of our graduate students.

In my lab, the demand of doing high-level mechanistic studies using genetic model organisms has also required long years from some of the more recent graduate students, which has decreased the enthusiasm in recruiting students into my lab.

Many of today’s students prefer fields like bioinformatics rather than experimental genetics for understandable reasons.

When did you know you would devote your career to molecular biology?

In graduate school. Biology was not my choice of major when I entered college, and I went to graduate school because it was my best option in life.

I started to like it towards the end because I realized that I was pretty good at research. The independence my advisor granted me also made the key difference. It is hard to enjoy doing science if all you do is follow someone else’s instructions.