Planetary scientist honored for his cosmic perspective

A CU Boulder planetary scientist is this year’s recipient of the Richard H. Emmons award for ‘extraordinary teaching’

For Nick Schneider, teaching isn’t just something that he has to do—it’s his passion. And one that’s being recognized by the Astronomical Society of the Pacific (ASP) with this year’s Richard H. Emmons award.

This award, which recognizes extraordinary teaching in astronomy, is the only such award given at the national level, and Schneider is the first recipient to focus on planetary science, rather than astrophysics, since the award’s inception in 2006.

“This (award) epitomizes what the University of Colorado gives faculty as a challenge and an opportunity: go do the best you can in research and share it with the world and go do the best you can in teaching and share it with the students,” said Schneider, a professor in the Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences and in the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP).

And Schneider has done that in spades, winning awards for both his research and teaching, with the Richard H. Emmons Award being his most recent.

Nick Schneider, a planetary scientist at CU Boulder, is this year's recipient of the Richard H. Emmons award.

The annual Richard H. Emmons Award recognizes outstanding teaching for non-science majors in college-level introductory astronomy courses. Schneider is this year’s recipient for his commitment to teaching, his innovative teaching methods, and for being a co-author on The Cosmic Perspective, a highly regarded textbook that, while now a staple in many introductory astronomy classrooms, was initially partially inspired by Schneider’s own teaching experience.

The story began when Schneider arrived on campus 30 years ago.

He was preparing to teach his very first astronomy class and picked up the textbook for the course. What he found, though, was a dated approach—a so-called “march of the planets” akin to something found in a child’s elementary school classroom—in which students learn planetary science by learning the planets and random facts about them.

This bothered Schneider, who felt that this method didn’t teach students what they wanted to know: how the planets work. He decided to create his own, more modern, approach that, not only taught the planets, but also how they fit into everything else in the cosmos—a “cosmic perspective.”

This new teaching tactic not only focused on the material students learned, but also how they learned it. Gone are the days in the Duane Physics and Astrophysics Building where introductory astronomy students sit passively, listening to the “sage on the stage.” Now, students are expected to participate in these interactive lectures through clicker questions and learning assistants that float around the classroom, assisting in discussions and encouraging student engagement in the subject matter.

“If education were just a matter of listening to the best lecture then we’d all be replaced with Carl Sagan or Neil deGrasse Tyson in video, but that’s not the way it works,” commented Schneider. “The best education happens in an interactive environment where your understanding is challenged and tested and you’re encouraged to try it out, even in the large classrooms. That’s where the learning really takes place.”

And that dedication to learning and improving how astronomy is taught has also helped others, which is something Schneider would like to continue doing.

“His selfless dedication to undergraduate education has also helped me—and I suspect many other colleagues—to become a better teacher,” one unnamed nominator told the ASP.

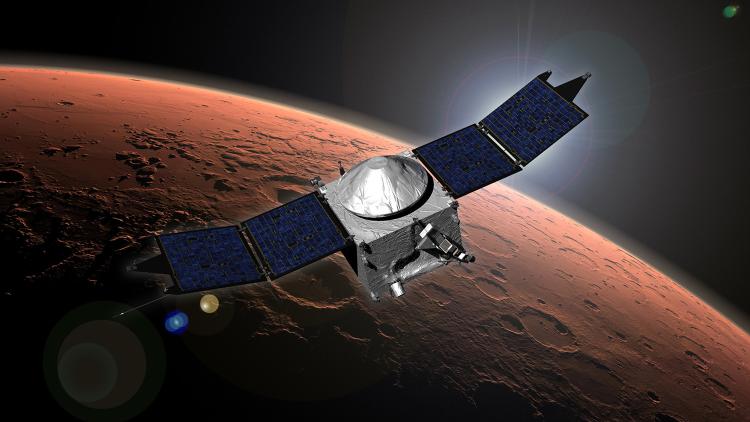

In addition to his teaching, Schneider is also a distinguished planetary scientist, working on projects like NASA’s MAVEN mission to Mars and the European Space Agency plan to visit and explore the Jupiter system.

This image shows an artist concept of NASA's Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) mission. (NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center)

Rather than being two separate things, Schneider says these accomplishments complement and enrich each other.

“It’s really exciting for me to bring a discovery that I or my team have made in the course of our research right into the classroom, and there are oftentimes when students in my class know things before the rest of the scientific community does. Students know that it’s something special too, and it only happens at a space-faring university like the University of Colorado.”

Schneider’s accomplishment will be recognized at the annual ASP Awards Gala on Nov. 9, 2019, in the San Francisco Bay Area.