Inventing Modern Japanese Man

Lesson (pdf)

Handout 1

Handout 2

Handout 2 Key

PowerPoint

Authors:

Ted Pierce, Marshwood High School, South Berwick, ME

Matthew Sudnik, Central Catholic High School, Pittsburgh, PA

Introduction

What did it mean to be modern, for nations and people, in the early 20th century? One salient aspect of modernity is the dynamic, shifting roles and identity of men and women within society, the economy, and the family. We often look at the shifting roles of women as a lens into the modernization process and experience. As one example, as women received more education in many societies in the late 19th and 20th centuries, they also sought and won greater social and economic empowerment. As women’s roles changed, men recalibrated their identities. Some recommitted to the traditional patriarchal norms while others liberated themselves from these erstwhile expectations. The shifts in gender roles and identities were no different for Japanese men and women as Japan transformed into a modern nation and society. Through the Meiji, Taishō, and early Shōwa periods (1868-1930s), as Japan industrialized and modernized, men as well as women experienced this dynamic shift in gender identities.

In this lesson, students explore images of the various “male identities” constructed beginning in the late 1800s. Some of these identities—the head of the household and the soldier—were intentional constructions of the Meiji government as part of the project of building a modern nation state. As heads of household, men had a paramount role to serve the nation by creating strong, productive families who embraced new national values. Men also had the critical responsibilities of protecting the nation through military service and/or contributing their individual industry to enrich the nation. Modernization, the infusion of Western culture, and the resulting social and economic change engendered other male roles—political radical and protester, breadwinner, the mobo (modern boy)—at the beginning of the 20th century. These roles might be seen as antitheses of the model male roles. As influences that would undermine the development of a strong and unified state, such roles were often perceived as a threat to Japanese culture by conservatives and traditionalists as well as by the modern government of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Grade Level/Subject Area: High School/Human Geography, World History

Time Required: 1 pre-class homework assignment and 1-2 class periods

Materials

For Students:

- Handout 1: Selected Writings on the Invention of the Modern Japanese Man

- Handout 2: Analyzing Historical Images

For Teachers:

- PowerPoint: “Picturing” the Invention of the Modern Japanese Man; Projection equipment

- Handout 2 Key

Objectives

At the conclusion of this lesson, students will be better able to:

- Understand the role that the state played in molding men’s roles and identities as the Japanese government built a modern nation state in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

- Explain various male roles in the modern Japan of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including ways in which men’s roles and identities changed organically vis-a-vis the evolving self-identity of women, who came to see themselves in non-traditional ways.

- Analyze the emerging roles of men in modern Japanese society in terms of broad themes of modernization, including nationalism, militarism, industrialization, imperialism.

- Understand identity as a socially constructed phenomenon that changes across time and place.

Essential Questions

- What was the duty of citizen to society, of man to state in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Japan?

- How did the identity of the Japanese man change because of reforms in the late 19th and early 20th centuries?

- What was the balance between individual life and rights and duties to the state in Japan during this period?

- How did visual messages promote ideals of men’s roles within a modern state? What roles and responsibilities were promoted through visual media?

Teacher Background

The modernization of Japan between roughly the 1880s and the 1930s dramatically changed not only Japan’s economy and political system but also Japanese culture. In exploring this period with students, it is important to emphasize that Japan’s path to modernization was both unique and a part of global trends. Modernization did not make Japan the same as the West. As historian Andrew Gordon writes in A Modern History of Japan, “the revolution that began in the 1860s was a Japanese variation on a global theme of modern revolution” (Gordon 2014, 62). However, unlike Europe, the Japanese had a “revolution from above.” Members of the samurai, the elites of the old order, led the movement for change. The changes imposed by the Meiji government were a direct response to the reformers’ criticism of the Tokugawa era. They saw in the Tokugawa system “military and economic weakness, political fragmentation, and a social hierarchy that failed to recognize men of talent” (Gordon 2014, 62).

Out of this critique came a new system emphasizing military and economic strength through unity and centralization. Modern Japan also built a generation of men who labored for themselves as well as national prosperity. The revolution in Japanese male identity was on display in the popular artwork of the time.

While there is a lot of information on changing roles of women, the scholarship is thin on the effects of modern nation-building on the changing roles of men in Japanese society. However, while the change in women’s roles might be perceived as more radical or exceptional, it is clear from research that men’s roles changed as well. This lesson includes written and visual sources that demonstrate competing views of the man’s role in Japanese society during the Meiji, Taishō, and Shōwa eras. The topic is an interesting area for students to explore because gender is an important aspect of identity as well as cultural and political geography. Throughout world history, gender has been an ongoing concern of religious and political institutions. The degree to which people conform to designated gender roles may have a significant impact on changes in society. For example, women’s education and status are linked to birth rates. While male roles may not be linked so closely to demographic forces, men’s embrace or rejection of conformity can significantly unsettle society’s traditions. Modernization in Japan required the obedience of the male as a worker and soldier. Male refusal to conform could have repercussions for security and the economic strength of the state. Finally, the topic of gender remains salient within Japanese culture today, when more young men and women are delaying marriage and even shunning adulthood, choosing instead to stay in their parents’ households.

While the male roles emerging at this time cannot be confined to any one category, we use two categorizations to help students consider and analyze changing roles of men during this period: (1) male roles that support the nation and (2) male roles that challenge the national order.

Male Roles that Supported the Nation.

Male roles that supported the nation included head of household, worker, and soldier. As husbands and fathers, men contributed to national unity, modeling respect for authority and inculcating social values. As workers, at all levels, men also strengthened the national economy. In 1873, the Meiji government decreed universal conscription. The use of patriotism to induce military service was a hallmark of modern nationalism. In their roles in the military, men strengthened and protected the nation.

Male Roles that Challenged National Order.

On the other hand, modernization engendered another set of roles and identities that the empowered elite perceived as threatening to society and the new nation state. For example, the laborers’ identity emerged from the Meiji project of industrialization. However, just as in the West, the laborers often turned radical as they demanded more just working conditions. Similarly, those left out of the Meiji modernization miracle—unemployed and impoverished segments of society—turned to protest.

The tumultuous relationship between Japan and its neighbors also led to social protest. For example, while Japan was victorious in the Russo-Japanese War, a conflict driven by Japan’s imperial ambition, the Japanese public did not accept the conditions for peace. The public resented their government’s losing the claim to monetary reparations and territorial gain after a war that had been so costly. The image of the 1905 riot in Tokyo depicts the Japanese public’s response to the treaty. According to Andrew Gordon, “For Japan’s bureaucratic and military rulers, the Hibiya riot was a frightening event. By their actions as well as in speeches, people were saying that if they were to pay for empire, and die for it, their voice should be respected in politics” (Gordon 2014, 132).

Finally, the introduction of Western dress and music, coupled with rising prosperity and disposable income among urban Japanese, led to changes in fashion and customs. The mobo, or “modern boy,” rejected many of the traditions as well as contemporary norms of Japanese society to embrace a lifestyle of freedom and individualism. In short, modernization led to a range of roles and identities, from male conformity in service to the nation to male individualism and radicalism.

Preparing to Teach the Lesson

- Familiarize yourself with the images in the lesson PowerPoint, the background on the images provided in the Handout 2 Answer Key, and the overall lesson and handouts prior to class.

- Copy handouts for all students. Distribute Handout 1 prior to the first day of the lesson, as required advance reading. Have Handout 2 ready to distribute on the first day of the lesson.

- There are many ways to present the PowerPoint images contained in this lesson. The images are provided in a PowerPoint, which can be projected on a whiteboard or shared with students via personal devices. Either prepare to show the slideshow included in this lesson, or post it to your course webpage for students’ personal viewing.

Lesson Plan: Step-by-Step Procedure

- The day before the lesson, distribute Handout 1, Selected Writings on the Invention of the Modern Japanese Man. This handout contains excerpts from the writings of Fukuzawa Yukichi and Yosano Akiko. Note: In this lesson, the Japanese convention of family name first, given name second is used. Thus Fukuzawa and Yosano are family names. Alert students to this naming order. Provide the students with the following background on these two writers prior to reading the excerpts:

- Yosano Akiko (1878-1942) was the pen name of one Sho Ho. Yosano Akiko was a leading feminist and social critic in early 20th-century Japan. In addition to writing political and social commentary, she is considered one of the most significant Japanese poets of the Meiji, Taishō, and Shōwa eras.

- Fukuzawa Yukichi (1835-1901) was a Japanese philosopher and political writer of the Meiji period. He was a leading proponent of modernization; in the early stages of nation-building, he embraced the ideas of Europe’s Age of Enlightenment such as the power of reason and intellect over tradition. His writings were influential in the Meiji Era, and he is credited with helping to modernize Japan. He is often compared to the Enlightenment philosopher Voltaire.

- The Importance of Their Writing. Yosano Akiko and Fukuzawa Yukichi were influential public figures who articulated strong philosophies on the roles of individuals in Japanese society during this period. They each made significant contributions to the modernization of Japan. In the excerpts of their writings in Handout 1, these writers challenge foundational Japanese institutions and national policies of the times—the family, business, war. While Fukuzawa, writing during late Meiji, promoted and endorsed the Meiji government’s broad reform agenda, Yosano Akiko, writing several decades later, was far more critical of changes brought about by modernization. An example of her position is reflected in her poem about the militarization and role of the Japanese soldier. Both writers should help students see the changing ways of thinking of daily life and gender roles during the period of Japan’s modernization.

Ask students to read the selection and respond to the two questions on the handout in writing for homework, prior to the next class session.

- Open the lesson by asking students questions about the short reading from Fukuzawa Yukichi and Yosano Akiko. The essential question to guide this discussion is: What is the role of the individual in the process of nation-building in early modern Japan? Use the following questions to stimulate discussion:

- In your life, do you have a duty to your individual self, your family, your nation?

(Answers will vary.) - How does Yosano Akiko describe modern Japanese men?

(In “The Value of Work,” she writes that men are primarily concerned with money. In “My Brother, You Must Not Die,” she discusses the man as soldier and questions the agenda of war, including the emperor.) - Why might the Japanese state from 1890-1937 encourage men to be industrious and concerned with making money? Why promote the conscript army?

(Men were encouraged to work for the benefit of the nation and to strengthen their family, which was a microcosm of the nation within the household. The household was meant to promote the national agenda. As for war, beginning with the Meiji Restoration, all young men were required to give their service to the nation.)

Throughout the discussion, jot student answers on the board. To culminate the discussion, consider the responses as a whole. What roles and responsibilities emerge? Ask students why these might be important roles in a nation trying to modernize and build a sense of nationhood.

- In your life, do you have a duty to your individual self, your family, your nation?

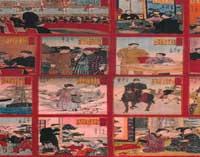

- Next, share the image of the Japanese board game, Progression of Education for Men (1890) on the whiteboard or projector. This is the first image in the PowerPoint. Provide the following background on this game:

- Inexpensive, paper board games, called sugoroku, were very popular in Meiji and early 20th-century Japan and can still be found today. These Japanese board games were distributed free in magazines and newspapers. Often these games told a story or served an educational purpose, conveying values or goals of the broader society through the goals and steps of the game.

This game, Progression of Education for Men, tells the progression, through images and stops on the game board, of a Japanese man’s public life cycle from birth through the stages of adulthood. It is important for students to note that the progression depicted was an ideal of the middle and upper classes in Japan at the time. While not explicitly a work of propaganda, the game has a specific message of conduct and responsibility to the nation that supports the larger project of modernization and patriotism. It underscores the importance of public life and responsibility for the upper class man in Japanese society.

- Inexpensive, paper board games, called sugoroku, were very popular in Meiji and early 20th-century Japan and can still be found today. These Japanese board games were distributed free in magazines and newspapers. Often these games told a story or served an educational purpose, conveying values or goals of the broader society through the goals and steps of the game.

- As a class, begin to analyze the board game, starting with the image in the bottom right-hand corner (the start of the game) and working across and up from right to left (the end of the game). Ask the students to describe what they see in each image. In particular, guide students to look at the lifestyle of the man in each image. Ask students to answer the following questions: What is the man doing in each block? How is he dressed? Is his attire traditional Japanese or Western? How does he advance in his life? How does he advance in his career? Encourage students to make notes as the discussion proceeds.

- Show students the second PowerPoint image, entitled “A Happy Worker Makes a Happy Home” (1932) and explain that this poster has a very different origin; it was part of an advertising campaign by a labor welfare association in the early 1930s. Ask: How do these two different pieces—the board game and the labor welfare association poster—convey national expectations of the Japanese man? What is the message in the game? In the poster? (Students should be able to recognize that the labor poster—like the board game—also promotes broader government goals for the population, portraying the Japanese man who is working hard both for the national economy and his household.) Guide student discussion so that students can identify the following themes in the two visuals: nationalism, military service, the connection between the national economy and household economy, connection between progress in one’s life and progress of the nation. Write these major themes on the board.

- Distribute Handout 2 as the class views the remainder of the slides in the PowerPoint collection. Note that, with the exception of the first image, each image first appears individually and then paired with another image. On Handout 2, students are to note both what they see in each image (formal) and the connection between the male image and the modern Japanese nation of the early 20th century (factual). For example, as you project image 1 from the PowerPoint collection on the board, the students should complete questions 1 and 2 on the handout by writing next to #1 what they see in the image of the sugoroku board game (question 1) and connections between the image and the modern Japanese nation (question 2). Proceed through all the images in the PowerPoint. Project all images so students can view the continuity and change across all of these images.

If the students have personal devices, upload the PowerPoint of images on a course webpage and encourage the students to view and write about the images. - As a final step in the visual analysis, direct students’ attention to the final slide contrasting the modern boy (mobo) with the soldier. Focus students’ attention on formal aspects of the images such as the placement of the text, the contrasting backgrounds (street with modern urban landscape vs. the traditional samurai castle, etc.). Then ask students the following questions:

- What contrast or confusion do these two images create?

- What makes each image appealing and compelling?

- What do these images convey about the role of the state in the lives of Japanese men in this period?

- How did the state’s project of nation-building reinforce certain ideas of being a man?

- How did the state benefit or suffer from these various iterations of Japanese men?

- Conclude the lesson by having students individually complete question 3 on Handout2. Provide additional instructions and objectives of the writing assignment, as follows:

- Write about the images in terms of political, economic, and social function, as well as how these images of the male changed across time and expressed nationalism, militarism, industrialization, and imperialism. These features defined Japan as a modern state on par with the West. For the alternative male types—the protestor, the socialist, the modern man—which of these national ideologies were they challenging? What were their grievances with the four ideologies?

- This synthesis activity can be completed briefly as an “exit ticket” or as homework, which would allow students to compose a longer essay.

Assessment

The synthesis writing activity can serve as the assessment for this lesson. In the essay, the student must describe with precise examples how images of the male changed across time. They should draw connections between the image of the male and concepts of nationalism, militarism, industrialization, and imperialism. For example, the student should be able to identify which male images promote the national interest and which male responsibilities—the family man and businessman—promote the national economy. Students should be able to identify militarism and military service as a salient image in both the sugoroku game and the military poster. These political and economic identities helped define Japan as a modern state.

Standards Alignment

Common Core:

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.9-10.1: Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.9-10.7: Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse formats and media, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.9-10.9: Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take.

National Standards for World History:

- Era 7, An Age of Revolutions, 1750-1914, Standard 4: Patterns of nationalism, state-building, and social reform in Europe and the Americas, 1830-1914

- Standard 5: Patterns of global change in the era of Western military and economic domination, 1800-1914

- Standard 6: Major global trends from 1750-1914

- Era 8: A Half-Century of Crisis and Achievement, 1900-1945, Standard 1: Reform, revolution, and social change in the world economy of the early century

References

Gordon, Andrew. A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present. 3rd edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Additional Resources

Dower, John W. A Century of Japanese Photography. London: Hutchinson, 1971.

Duus, Peter. Modern Japan. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998.

Gordon, Andrew. A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present. 3rd edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Morse, Samuel Crowell, et al. Reinventing Tokyo: Japan’s Largest City in the Artistic Imagination. Amherst, MA: Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, 2012.

Sato, Barbara Hamill. The New Japanese Woman: Modernity, Media, and Women in Interwar Japan. Durham: Duke University Press, 2003.

Created 2015 Program for Teaching East Asia, University of Colorado Boulder.

Becoming Modern

- Meiji and Taishō Japan: An Introductory Essay

- Voices from the Past: The Human Cost of Japan’s Modernization, 1880s-1930s

- The Nature of Sovereignty in Japan, 1870s-1920s

- A Window into Modern Japan: Using Sugoroku Games

- Moga, Factory Girls, Mothers, and Wives

- Inventing Modern Japanese Man

- Voices of Modern Japanese Literature

- Negotiating Relationships: United States and Japan, 1905-1933