Spruce Gulch: Grounds for Discovery

It was a hot summer day in the early 1990s when Linda Holubar Sanabria (A&S’67) spied the enemy. Tall and deceptively pretty, bearing its hallmark lavender-colored, black-tipped flowers: the spotted knapweed. This noxious weed had quietly claimed Holubar’s family ranch as its home, and she soon discovered it was taking up residence on at least 50 acres of the sprawling 493-acre property — of which 476 acres are now known as the Spruce Gulch Wildlife and Research Reserve — which Holubar inherited from her family in 1994.

For the next 15 years, Holubar dedicated the quiet of dawn and the cool of dusk to eradicating the invasive plant, which arrived via contaminated batches of grass seed dispersed by the U.S. Forest Service after a 1988 fire. Leaving the knapweed unchecked was not an option for Holubar and her spouse, Sergio Sanabria (A&S’66; Arch’70; MArtHist’75), as they knew this would result in soil erosion, displaced vegetation and overall devastation to the land. So, for thousands of hours, Holubar labored over the acreage.

“At first, I felt very small as I began removing one plant after another from an endless sea of them,” said Holubar. “They ranged from taller than me to tiny seedlings.”

Though she made substantial progress, the effort needed a boost — not from harmful herbicides, which would contaminate the water and land, but from a more creative (and hungry) solution: weevils.

A Symbiotic Friendship

In 2001, during the thick of her weeding efforts, Holubar learned about a successful experiment at CU Boulder’s Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR). The project demonstrated that biocontrol insects (in this case, weevils) could greatly reduce densities of an invasive knapweed — similar to the unwelcome foe on Holubar’s land.

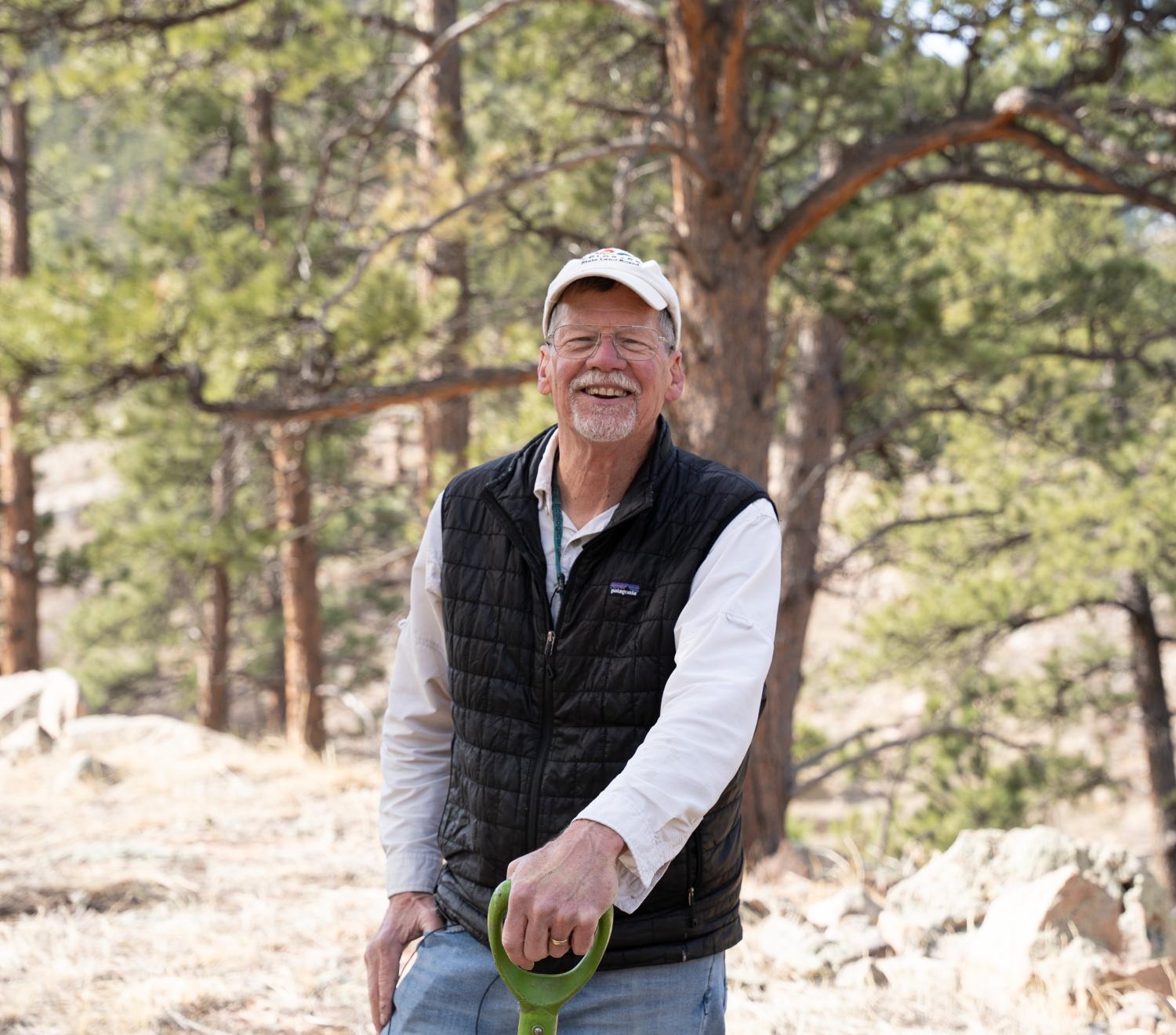

Putting her hope in these knapweed-eating weevils, she called the lead scholar of the experiment, ecology and evolutionary biology professor (now emeritus) Tim Seastedt.

“Field ecologists don’t pass up opportunities to leverage a new field site, and Spruce Gulch is special,” said Seastedt. He noted that the innovative insect approach, in addition to preserving good vegetation, could save landowners thousands of dollars in management costs.

Through a combination of hungry weevils and volunteer weeding efforts, the project proved successful over time and demonstrated the effectiveness that non-chemical methods can have on an invasive plant species.

The experiment also opened the door for additional ecology projects on the property — marking the start of what would become a 24-year symbiotic friendship between the university and land, and what would eventually result in a landmark gift.

Volunteers from a co-sponsored U.S. Forest Service event remove invasive spotted knapweed from an upland meadow on the Spruce Gulch Reserve.

Inheriting a Legacy

Holubar’s connection to the wildlife reserve began nearly a century ago, when her maternal grandmother, Irma Freudenberg, purchased part of it in 1927. With the help of her children, Freudenberg established a ranch on the picturesque land that Holubar’s parents, Alice (A&S’33) and LeRoy Holubar (ElEngr’36), later expanded in 1962.

Boulder’s mountainous terrain fostered the family’s passion for the outdoors. Holubar’s parents were pioneers in developing and sourcing climbing and expedition gear through their business, Holubar Mountaineering (which an interim owner later sold to The North Face). LeRoy Holubar, a CU mathematics professor, also helped establish the Rocky Mountain Rescue Group and the first Boulder climbing school.

Upon Freudenberg’s death, Holubar’s parents inherited part of the land and expanded it to what is now the Spruce Gulch Reserve. The site has been sculpted by history — from serving as hunting grounds for Indigenous peoples like the Arapaho, to sustaining mining and logging operations, grazing and agriculture, plus wildfires and floods.

“Having grown up on this land and having it be a part of my family for almost a century, I view it as my heart and soul and want nothing more than to protect it,” said Holubar.

Her love for the reserve and dedication to conservation meant diligently seeking out its next caretaker — a role that, after withstanding weeds and weevils together, CU Boulder was ready to undertake.

Acres for Academics

Primed to steward Holubar’s family legacy of environmentalism into the future, CU Boulder assumed ownership of Spruce Gulch in June of 2025. Holubar’s generous 476-acre land donation was accompanied by endowment funds, as well as a conservation easement with Boulder County.

The site and funds, valued at a combined $10.4 million, are managed by INSTAAR and support studies across the sciences, humanities and fine arts. From biologists to visual artists, the reserve and its endowment will enrich and support studies by academics from many departments, opening new educational possibilities across disciplines.

“Sergio and I wanted to discourage an inevitable disciplinary blindness by opening the site to as many different worldviews as possible,” said Holubar.

For her commitment to conservation and ensuring the protection of the wildlife reserve, Holubar received Boulder County’s 2025 Land Conservation Award. And, for their outstanding community partnership and collaboration on the Spruce Gulch project, Boulder County Parks & Open Space was awarded the Blue Grama Award by the Colorado Open Space Alliance.

A living laboratory, Spruce Gulch features canyons and cliffs intermixed with forest, savanna and prairie meadows. Its abundance of research opportunities has already aided CU faculty and students in producing 29 scholarly publications, plus chapters in six doctoral dissertations, three master’s theses and four undergraduate honors theses.

“The acquisition of Spruce Gulch allows us to pursue essential science relevant to the grasslands and foothills region, where most of us live,” said Seastedt, director of the reserve. “Therein lies the magnitude of this gift.”

Photos courtesy Tim Seastedt

Ecology and evolutionary biology professor (now emeritus) Tim Seastedt.