How Did Everything Get So Political?

Why do some issues become politicized? CU experts explain why and how voting rights, climate change and abortion became rallying cries for political parties.

Amid hills lined with grape vineyards and peach orchards, Doug Spencer, a CU Boulder associate law professor, found himself sitting in a room in Palisade, Colorado, meeting with locals about how to address the growing polarization in politics. The energy changed in the room when people realized that shifting conversations to localized issues like water rights rather than culture war issues could create more common ground.

But it’s not as simple as it sounds.

“Every issue can be branded by a political group like a corporation brands their product,” Spencer said.

It’s easy to see how with a hefty marketing budget and consistent messaging, any issue can become packaged with a red or blue ribbon to become a political product. But how exactly does something seemingly apolitical become a wedge that pits political parties against each other?

In a nutshell, the answer lies largely in three factors: if an issue helps reinforce a political party’s identity; what decisions the Supreme Court makes; and how much private money, particularly in the form of lobbying, enters the picture.

Issues As Rallying Cry for Voters

Sometimes, the road from a general-interest issue to political rallying cry is relatively straightforward. The issue just happens to be in the right place at the right time for a political party to swoop down, pick it up and run with it.

Climate change was merely an environmental issue in the 1970s and 1980s when oil and gas executives acknowledged carbon dioxide’s effects on Earth’s climate. And as late as 1989, Democrats, Independents and Republicans were equally “worried” about climate change, according to a poll cited by environmental studies assistant professor Matt Burgess.

So, why did climate change become politicized? Scholars, pundits and politicians often point to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, when 150 nations pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The U.S. signed it, but the Republican-controlled Senate refused to ratify it, arguing it would harm the economy. Fiscally conservative Republicans felt the protocol put too much of the financial burden on developed countries like the United States without asking developing countries to do the same, and arguably, they may have been right. And as Burgess points out, signing it seemed to go against Republican rallying cries around corporate deregulation and free-market capitalism.

Like the Republicans in Congress, conservative Libertarian Americans questioned why corporations and the public should pay a high price to slow climate change, especially since it was impacting so few Americans. In the 1980s and 1990s, there was more at stake economically to move from fossil fuels to renewable energy. Today, renewable energy is often the cheapest form of power. But it wasn’t in the 1980s and 1990s.

“Twenty years ago, the downsides of climate change were seen as far off and the economic pain was seen as real and imminent,” said Burgess. “Now both of these things have changed.”

Conversely, Democrats — spearheaded by Vice President Al Gore — saw climate change as a moral issue that needed regulation, regardless of its cost or that its impacts weren’t immediately felt. Flashforward to 2019 when that moral take on climate change took center stage in the Green New Deal in which progressive Democrats sought to bring greenhouse gasses to net-zero and address economic inequality and racial injustice.

Like climate change, abortion also got swept up into partisan politics.

When Roe v. Wade passed in 1973, it gave women the right to an abortion — but it wasn’t immediately a partisan issue. In fact, the Supreme Court was majority Republican-nominated, and five of the six Republican appointees voted to legalize abortion.

“In Roe v. Wade, the court was divided more on legal types of things,” said CU Boulder law professor Jennifer Hendricks. “It wasn’t until after Roe v. Wade that there was a synergy in the Republican party with their vision of politicizing abortion as an issue.”

That synergy took center stage at the 1980 Republican Convention in Detroit, as Republicans campaigned on “preserving traditional family values” and called for stronger families and a constitutional amendment to protect the lives of unborn children. Some scholars assert that the religious right’s rising power, plus the mass exodus of conservative Southerners from the Democratic party, moved abortion to the center of the Republican family values platform.

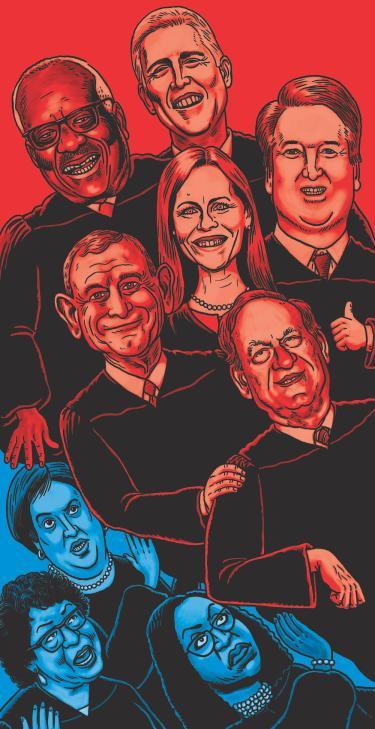

By 1992, the Republican Convention platform called for the “appointment of judges who respect traditional family values and the sanctity of innocent human life.” It has since guided a decadeslong openly public Republican strategy of appointing pro-life judges at all levels.

Yet there’s another force contributing to turning certain issues partisan — the Supreme Court.

Supremely Transformational

Yet there’s another force contributing to turning certain issues partisan — the Supreme Court.

Take 2013, for example, which was packed with milestones. Apple released the iPhone 5s with touch ID, Lance Armstrong admitted on Oprah to doping during his Tour de France wins, and the Boston Marathon bombing shook the country. That same year, the Supreme Court struck down a key provision in the Voting Rights Act that previously required states with a history of racial voter discrimination like Mississippi and Texas to get approval from the federal government before making any changes to voting procedures. Both associate law professor Douglas Spencer and women and gender studies associate professor Celeste Montoya point to this ruling, known as Shelby County v. Holder, as a major turning point for partisan battles related to voter rights.

“Part of the justification from Justice Roberts was we don’t need this anymore because we’ve moved beyond this,” Montoya said. “The very next day states were able to establish laws that restricted voting rights. The shift from voting rights to voting privilege is pretty significant and has opened the door to the notion there are right voters and wrong voters.”

Within 24 hours, Republican-dominated Texas, Mississippi and Alabama implemented strict photo ID laws. By 2016, the ACLU was challenging 15 states that passed voting restrictions before the 2016 presidential election. The ACLU notes that red states tend to pass restrictive voting laws while blue states tend to pass expansive voting laws.

“Democrats say everyone should vote, and Republicans say that Democrats are only saying that because it will help them,” Spencer said. “It starts to move the conversation away from the root of democracy and democratic ideals.”

Dark Money

In the years since, it’s spurred a frenzy of private spending to influence election outcomes.

The rise of special-interest groups — that fund politicians and research — is also steering issues toward the partisan divide. In 2010, the Supreme Court, through its Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission ruling, allowed corporations and individuals to give anonymous, unlimited donations to political campaigns. This decision reversed 100 years of federal restrictions on corporate, nonprofit and labor union funding.

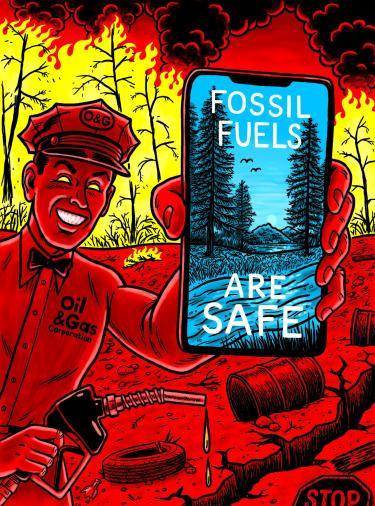

In the years since, it’s spurred a frenzy of private spending to influence election outcomes. In 2010, oil and gas companies donated approximately $35 million to U.S. congressional candidates. By 2018, this number ballooned to more than $84 million, according to a study published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Private money also funds thought leaders. In the case of climate change, billionaire industrialists and brothers Charles and David Koch gave more than $145 million to climate-change-denying think tanks and advocacy groups between 1997 and 2018.

“There’s the special-interests angle, where the fossil fuel industry supported misinformation about and denial of climate change,” Burgess said, noting it’s well-documented in books like Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming.

At present, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Delaware, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Minnesota and Vermont are suing five large oil and gas companies for their alleged role in delaying climate policy and increasing the climate impacts, risks and costs incurred by state governments.

Glimmers of Hope

The good news? Not all issues stay political. Spencer sees the rise in ranked-choice voting as a way to reduce acrimony in politics. With ranked-choice voting, you rank candidates in order of your preference. If someone receives 50% plus one of the votes, they win the election. If no one has the majority vote, the person with the fewest votes is eliminated, and the results are retabulated. This repeats until someone wins a majority.

Ranked-choice voting has been used in Maine and Alaska for statewide elections, and in cities like Fort Collins, Colorado, and Evanston, Illinois. U.S. Republican Sen. Lisa Murkowski won her 2022 election in Alaska via ranked choice voting, as did Alaska House Democrat Mary Peltola.

“It’s been shown to be more fair in terms of racial and partisan representation, and you don’t need districts to have ranked-choice voting,” Spencer said. “Big changes like this will be necessary to reset our politics.”

And curiously, Republicans and Democrats are finding common ground on climate change, at least at the state level. Last year, Burgess and researcher Renae Marshall looked at nearly 1,000 decarbonization bills that passed and failed at the state level between 2015 and 2020. Republican-controlled governments passed almost one-third of decarbonization bills.

“The boom of renewables is creating economic opportunity,” Burgess said. “If you look at the 10 congressional districts with the most planned and operational renewable energy capacity, nine of them are represented by Republicans in Congress.”

Why the Republican support? Market forces, combined with government research and development subsidies, have made renewable energy often cheaper than fossil fuels, Burgess said. Plus, more Americans are experiencing the effects of climate change firsthand, including devastating floods, intense heat waves and year-round wildfires.

So, why didn’t any Republicans vote for the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the first comprehensive climate legislation to pass in U.S. history, committing $360 billion to fight climate change? Burgess noted that Republicans supported similar policy elements at the state level. But it also included health care and tax provisions, which proved to be thorns in Republicans’ sides.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if one of Biden’s legacies is that he brought the Democrats to the center and passed climate change policy Republicans won’t want to get rid of and that they passed in their state legislatures,” Burgess said.

Illustrations by Ward Sutton