Confronting History with Action

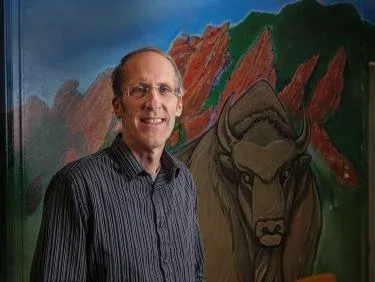

Andrew Cowell is a CU Boulder linguistics professor specializing in language documentation and linguistic anthropology. In 2003, he, along with faculty and students in the linguistics department, began documenting the Arapaho language to revitalize it for current and future members of the Arapaho nation. Cowell is also the director of the Center for Native American and Indigenous Studies (CNAIS), which, in partnership with the university and Indigenous community members, students, faculty and staff, helped develop a campus land acknowledgment that CU introduced in fall 2022.

Talk about CU Boulder’s land acknowledgment.

A good land acknowledgment does four things: It recognizes the current or former Indigenous inhabitants of an area. It recognizes that historically, the removal of Indigenous peoples from the land often involved severe injustices and that those historical injustices produce continuing inequities and harms in the present. And it commits to try to mitigate and address those continuing inequities and harms.

CU Boulder’s acknowledgment is a historical and moral document. Also very important is the commitment by CU to consult with tribes and local Indigenous people. You can’t truly address and mitigate harms unless you engage seriously with the communities themselves and get their perspective on issues and potential solutions. The big question now is, what actual concrete commitments will the campus make to back up its pledges?

How can CU continue to make amends for its early history with Native American and Indigenous people?

One important thing that has already happened is the 2021 state legislature bill providing in-state tuition for students from any of 48 tribes historically associated with Colorado, which CNAIS helped pass. The idea is that Arapaho, Cheyenne or other people would likely still be here in Colorado if not for forced removal, so they should still be eligible for in-state tuition. That has already helped greatly increase Native American and Indigenous enrollment.

As a state-funded institution, we have a broader responsibility to everyone in Colorado, and beyond, to address social issues and provide effective solutions. By reaching out to tribal communities, we can provide help with all kinds of things: language documentation and revitalization are one example, but there are so many areas for outreach and collaborative engagement with Native American and Indigenous communities.

What are some of the best aspects of having CNAIS affiliated with CU Boulder?

CNAIS is a teaching and research center where all students and faculty can engage. But we’re also a support center specifically for Native American and Indigenous students, staff and faculty. Since we have faculty and students from all over the campus, we connect interested folks with each other — engineers who might want to work on reservations, or tribes looking for expertise on climate change. In fact, it’s hard to imagine how CU could take on the moral commitments of the land acknowledgment without having a specific Native American and Indigenous-facing component like CNAIS on campus.

What sparked your interest in the Arapaho language?

What started out as a personal interest turned into a career choice.

My wife is Native Hawaiian, and I had learned Hawaiian and really gotten a lot out of that, so when I was hired at CU, I figured I should learn about the Indigenous languages of Boulder. The Arapaho were the people historically most present around Boulder. I realized there wasn’t a lot of published information, so I went to the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming to meet some speakers who said they could use help documenting their language. What started out as a personal interest turned into a career choice. You never know where things are going to lead.

What’s important when documenting a language?

Documentation is important for languages like Arapaho that are endangered, meaning there are no longer young or middle-aged fluent speakers. In such cases, documenting natural discourse — conversations, stories, songs, speeches and so forth — is key. If you want to try and revitalize a language, you need models to learn from — Native speakers engaged in everyday language activities and interaction. I’ve recorded dozens of hours of that kind of thing, mostly on video, so you can also see things like gesture, Plains Sign Language signs, body positioning, the way people use eye contact or not as they interact — subtle features that go into actual communication.

Are there other Native languages you hope to document and preserve?

I’ve written a grammar of the Aaniiih (or Gros Ventre) language of Montana, which will be published in the next year or so, and also done a bilingual anthology of legends and historical accounts in that language. I’ve also written a grammar of the Coast Miwok language of California, which will be finished once I look at some archival materials from the 19th century. I also have created databases of the Southern Sierra Miwok language and the Central Sierra Miwok language of California. More recently, I’ve been working with the Quechua language from Peru as well.

What do you do in your free time?

I enjoy hiking, camping, snowshoeing, birdwatching — generally engaging with the natural world. I really enjoy knowing the plants, being able to identify birds and animals, and having a very detailed interaction with the environment. That helps me with the languages, too, when I’m working to document Native names for various plants or animals or Native ecological knowledge.

What else should we know about you?

Honest cross-cultural engagement is hard work but very rewarding.

I’m a progressive, church-going United Methodist. One of the things I see at CU is a tendency for many students to view organized religion as being entirely conservative or entirely detrimental in relation to things like missionaries and Native people. That component is there, and many progressive religious groups are working to confront some of the highly problematic aspects of their past involvement with colonization or conquest — in a way similar to the Land Acknowledgment movement — and I’ve been involved in that. But at the same time, many of the Native Americans I work with are themselves Christians — and often simultaneously practitioners of Indigenous religions. So I think we need to keep a nuanced understanding of the very complex role of “the sacred” and not be automatically dismissive of organized religion — or, conversely, engage in simplistic caricatures of Native spirituality. Honest cross-cultural engagement is hard work but very rewarding.

Photos by Glenn Asakawa