From Soldier to Student

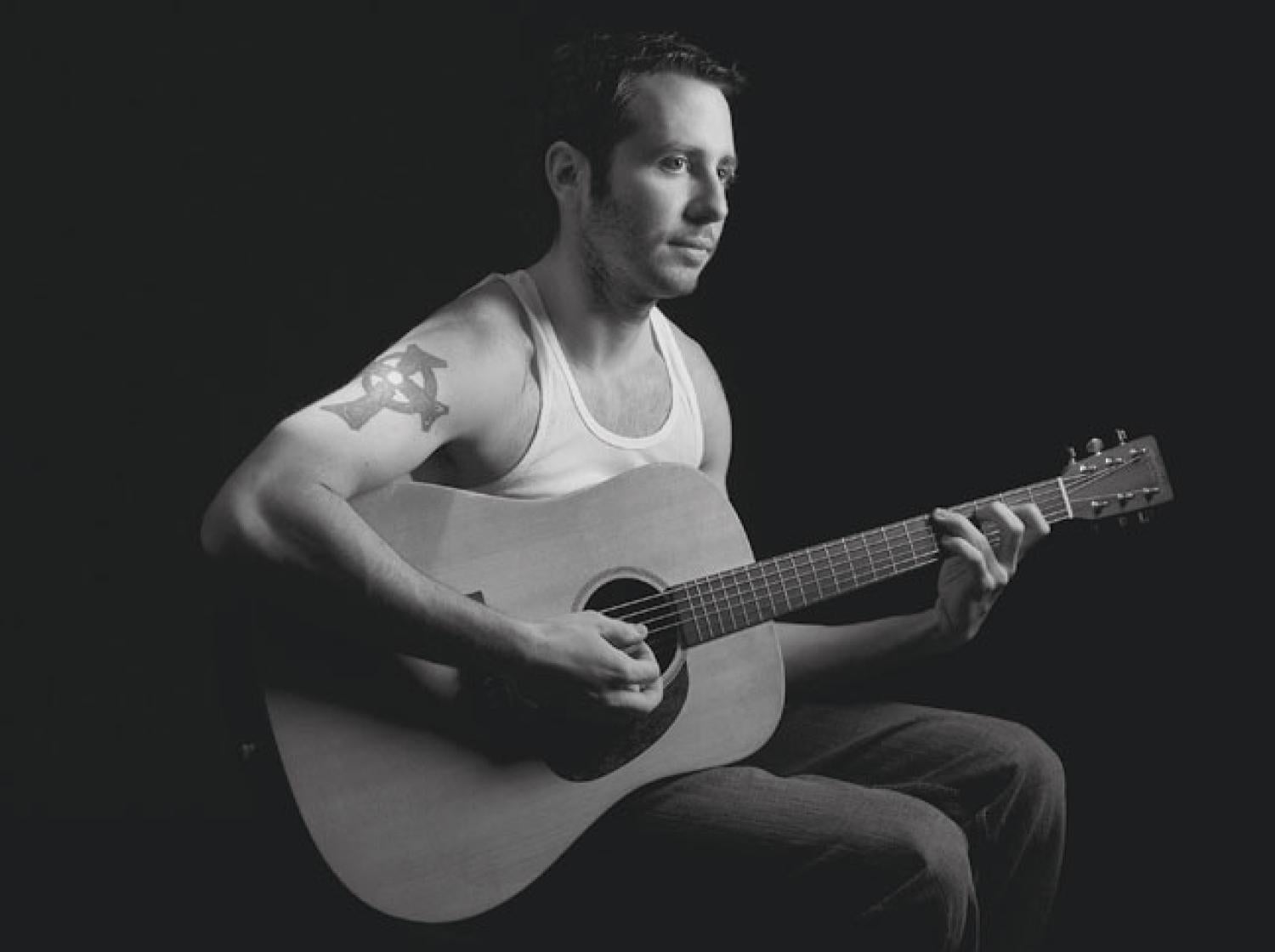

Army reservist Dave Hoch, 24, integrative physiology major, pictured with a tattoo commemorating his friend who died in Iraq.

“Sometime, I’ll tell you about ceilings,” former Army medic Dave Hoch says to me, his voice echoing in the empty staircase of the UMC.

Then he points upward, casually detailing the ways people can kill you from above. I look up and see the stark ceiling, but Hoch’s large brown eyes drift off, replaying scenes from the 16 months he spent in Iraq.

“I find my exits, and I look at ceilings for cameras,” he says, pointing to one obscurely located above the stairwell. “I always sit near the aisles in class. I don’t like hearing footsteps behind me, so I step aside to let people pass. I think it’s part of the reason I survived [in Iraq]. You either go through the motions or you end up dead in the water.”

Hoch is one of an estimated 400 military veterans who attend CU-Boulder today. They are single. They have families. They served in Iraq. They’ve never left United States soil. They look like any other student when they’re in civilian clothes. And they are used to being part of “we,” which makes the transition from team-oriented combat to “me-centered” college life all the more challenging.

Moreover, they are grossly outnumbered on campus in comparison to previous conflicts like Vietnam, Korea or World War II. In 1947, more than half of all CU students were World War II veterans. Despite the country’s involvement in two Middle Eastern conflicts today, there’s a wide cultural gulf between those who have served and those who haven’t. Creating a bridge for vets, CU became one of the first universities in the country to open up an Office of Veteran’s Affairs in 2007 — a campus office that disappeared after the Vietnam War ended.

The sacrifices of CU’s veterans resurface in the backwaters of their daily routines like the slow, persistent water of the Euphrates River cutting through time. Some are swept up by the emotional currents of battle, suffering from survivor’s guilt and haunted by the second that will last their lifetimes — when enemy fire swallowed the lives of their friends, commanders, boot camp instructors. Others celebrate the quiet victories of parenthood amid the freewheeling lives of their classmates. Many feel misunderstood, earnestly emphasizing their role to help people, not hurt them. A handful appear in this photographic essay, sharing glimpses of the poignant and intimate moments of their lives.

“I don’t watch the news much anymore because having been there [Iraq], you know what’s going on and news doesn’t portray the whole picture — just pieces. All of the time, it’s about soldiers killing civilians. Every once in awhile you hear about peace keeping. There were so many positive stories. Every month we held a medical screening for families. We’d give out drugs, bandage wounds and see upwards of 200-300 people a day, but you never hear about that.”

— Army reservist Dave Hoch, 24

Marine Lt. Justin Griffis (Bus’08), 26, pictured with his wife, Jen Griffis, and daughters Madison, 4, and McKenna, 16 weeks.

“You see a different perspective. Last night, I was holding my second child, McKenna, and you do have to relearn everything — swaddling, changing diapers, making sure they sleep on their back. I’m not a helicopter dad, but I am still more nervous for her than I was with my first.

I’m not wiser or smarter [than the younger students in my classes]. Some of these kids are ungodly smart. But you see a certain naiveté and the “I’m about me” mentality. I’m about my wife, my kids, my Marines. I can see it from a wider, worldlier perspective [after being stationed in Hawaii and Thailand]. But it’s not that hard [being a student]. I can be friends with anyone.”

-Marine Lt. Justin Griffis

“We ended up losing 34 guys [in Iraq]. Imagine 34 of your friends dying and you not being able to show any emotion for two to three months and then it hits you like a train. I wrote a journal there to keep me sane. I’ve seen a lot of Vietnam vets keep things in. It’s better to get it out of you. Those who don’t talk about it, it kills them.

Marine Sgt. Geoffrey Melvin, 24, environmental studies major with a minor in Russian.

I’m a thinker. When I was there, all I thought about was not dying and eating cheeseburgers. We would do anything to stay alive — sing songs to each other, talk about pizza, cheeseburgers. We got no sleep and after awhile, you don’t care. Sometimes you are sleeping at 2 a.m. or 2 p.m. You deal with what you got.

I have a lot of pride in everything we have done. I hold my shoulders high knowing that I worked hard and gave 100 percent.”

-Marine Sgt. Geoffrey Melvin

“My role model is my mother. She was in the Marine Corps for 20 years with six kids. I lost my son to sudden infant death syndrome when he was 3 months old. I thought, ‘Maybe I shouldn’t have gone back to work [as a Marine] when he was six weeks old. Maybe I could have been a better mother.’

Marine Staff Sgt. Samantha Martinet, 28, sociology major pictured with her daughter, Amara Bailey, 5, and fiancé Marine Sgt. Brad Dunlap.

When I found out I had to go to Rhode Island for six months, I knew I had to leave my daughter, Amara, who was going to turn two. I was upset and called up my mom and she said, ‘When we get off the phone, you think long and hard about your commitment to the Marine Corps and being a leader. There are times I left you and you turned out fine. The Marine Corps doesn’t need people like you if you can’t do what you’d ask them to do.’

I realized I had the courage to be a good Marine and not be upset with myself or feel guilty when I had to leave.”

-Marine Staff Sgt. Samantha Martinet

“I swing dance. I learned to swing dance in the Marine Corps. When I was stationed in Hawaii, I saw some people dancing and thought, ‘I want to learn that.’ I found out where the lessons were and found out I wasn’t that good. I got deployed for awhile, came back and got really into it. My social life was a little different than my work life, which was nice.

Former Marine Jack Oakes, 30, electrical engineering major, pictured with his wife, Sarah Failing Oakes (ChemEngr, MCDBio’00).

I met my wife at the Mercury Café. It was one of the most liberal places in Denver. I didn’t know it at the time, and you won’t find many Marines there. There are stars and moons on the wall and you can get vegan stuff there. I thought it was absolutely crazy, but so many people were there to swing dance. If you are going to experience a lot of things in the world, you have to be open.

Last summer I worked with Engineers without Borders in Rwanda and installed a solar lighting system on a school. It was jaw dropping.”

-Former Marine Jack Oakes