A Healing Lens

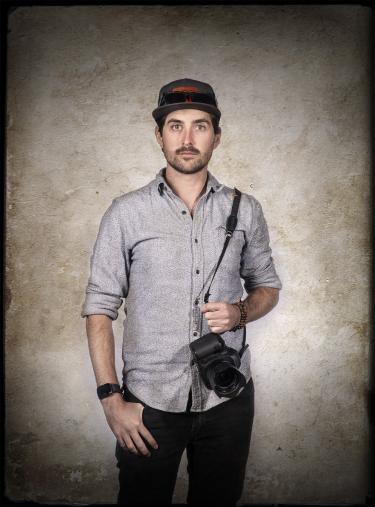

Ross Taylor, a photojournalist and faculty member at the University of Colorado Boulder, spent months documenting community trauma and healing in Boulder after the city experienced a mass shooting in 2021.

The shooting, which took place at the Table Mesa King Soopers March 22, 2021, left 10 people dead and the community reeling. In the days after, Taylor, an assistant journalism professor in the College of Media, Communication and Information, documented the community’s response and quickly realized there was more he could do. He began a long-term documentary project, gathering photos of the community as it recovered and hoping to aid in the healing process.

“I do know that when people experience trauma, if they feel less alone, it can aid to some degree in their healing,” Taylor said.

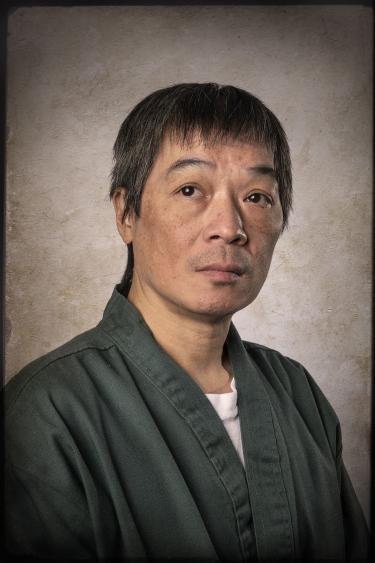

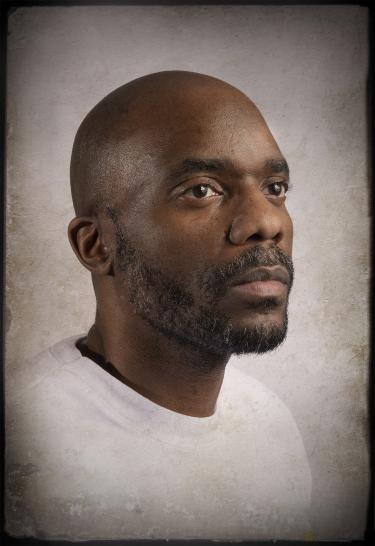

His initial project has transformed into Boulder Strong: Still Strong, Remembering March 22, an exhibit in March and April at the Museum of Boulder. Boulder Strong includes artifacts from the memorial wall next to the grocery store and over 70 portraits of people tied to the event, from CU Boulder students to mental health professionals and local police officers. The portrait project relied upon local groups, like the Museum of Boulder and Boulder Strong Resource Center, a multi-agency resource hub that aims to help community members heal, Taylor said.

“The response from the community has been incredible,” he said.

Taylor has won international and national awards for his photojournalism, including the National Press Photographers Association’s national photojournalist of the year award. Prior to joining CMCI, he worked for prestigious visual newspapers such as The Hartford Courant. His work has also been featured in The New York Times, The Denver Post, The Washington Post, USA Today and many others.

Taylor has frequently documented intense, emotional and intimate experiences. Working in Kashmir, India, he witnessed gun violence and poverty. He was assigned to document war scenes and trauma hospitals in Iraq and Afghanistan. Later, he documented families as they navigated pet euthanasia.

“I was very impressed with how sensitive he was and how sympathetic he was,” said senior journalism student Anna Haynes, who viewed the shooting from her apartment across the street and was one of Taylor’s participants. “He really was concerned with my response and my healing process and my relationship to [the shooting].”

In an interview with CMCI, Taylor offered a deeper look at the Boulder Strong: Still Strong project. Responses have been edited for clarity and length.

How did this portrait project come about?

After I took photos that week along the memorial wall, I just felt like there was something more to be done. And so I thought about the idea of doing a portrait project, but I felt like I needed a partnership to help elevate the mission. I approached the Museum of Boulder because they're the record of history in Boulder.

Who is featured in the portrait project?

At first it was smaller, but the more people heard about it, then it just exponentially grew and grew fast. We now have around 70 people, and we have key people anywhere from the store manager of the King Soopers, to the district attorney, to the person who shot the suspect, to many of the first responders, to mental health workers who are aiding in the healing of Boulder. I'm heartened by the response of the community.

How has your past work helped prepare you for this project?

Stepping out of the daily role that I had as a staff photojournalist and working at the university has offered me the opportunity to think in different ways and think of other ways of documenting events. This project, ostensibly, was meant to explore aspects of healing in the documentary form. Because I do know that when people experience trauma, if they feel less alone, it can aid to some degree in their healing.

What is important about this type of photojournalism?

Journalists are trained to be responsive to the events at hand or events that are about to happen a lot of times. We're less focused on looking back—that's not to say that never happens because people do memorial journalism all the time—but I don't think it's as active, and it's not a space that is promoted as much in newsroom culture. I think if anything, this project shows the community can oftentimes really rally behind an idea of a memorial or an archive approach to an event.

What have you learned throughout this process?

It shows the rippling effect of such a devastating event. I'm honored to better understand the individual [level] of this experience—one at a time, making these portraits and seeing just how deep and how impactful this event was for so many people. It just makes my heart go out to them. I care a lot more for Boulder now.

What would you recommend to your students or younger journalists who will have to cover tragedies in their careers?

It's twofold. One is to always move with care and respect for those experiencing trauma. But then also to move with care and respect towards themselves as a witness and someone who experienced it through others—to not minimize it and to take care of themselves.

Anything else you want to share?

I'm just reminded of the power of documentary work and how it can be a tool in healing, for sure. But I'm still working on the archives, so if somebody were to see this and want to participate, they can contact me.

Lauren Irwin graduated from CMDI with a degree in journalism in 2022.