First Peoples Worldwide Partners with Adasina Social Capital to Develop Comprehensive Indigenous Rights Risk Screen for Investors

Inadequate human rights protections for Indigenous Peoples in business operations often lead to risks with measurable material impacts and immeasurable harms to people. These impacts are evident in such instances as true cost of the Dakota Access Pipeline and the permanent loss of the Juukan Gorge, as well as through contemporaneous violations occurring on or near Indigenous lands from increased mining for the transition to clean energy economies.

Institutional investors therefore require reliable data 1) to perform comprehensive due diligence to avoid such risk, and 2) to make informed investment decisions that account for both the impact their investment has on Indigenous Peoples’ wellbeing and for the material impacts Indigenous rights violations might have on their portfolio.

First Peoples Worldwide has long experience developing these types of screens and gathering the necessary data to provide portfolio insights on Indigenous Rights Risk. In 1999, First Peoples Worldwide and Calvert Investments partnered to create the first Indigenous rights investment screen, which was used to train more than 600 brokers and evolved into investment drivers used by EIRIS, MSCI, Sustainalytics, and other major ESG research houses. In 2014, First Peoples Worldwide published the Indigenous Rights Risk Report, foundational research that companies and organizations continue to use to baseline structure screening protocols and guidelines.

A comprehensive Indigenous rights screen helps bring investors one step forward by showing that there are meaningful measures they can take to accurately and adequately screen for Indigenous Rights Risk.

Methodologies, Opportunities & Challenges

Since 2021, First Peoples Worldwide has partnered with Adasina Social Capital to create an Indigenous Rights Risk screen to help Adasina gain insights as to which companies to include or exclude in their portfolio.

Following modeling and testing phases, the screen provides two tiers of progressive risk capture. The first tier includes an exclusion screen based on five criteria that reflect the most severe and pervasive violations of Indigenous rights as generally defined by international law and specifically as articulated in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

The five criteria are:

- Exhibits a pattern, practice, or perpetuates a violation of the rights and protections of Indigenous Peoples.

- Demonstrates a pattern, practice, or perpetuates criminal or exploitative behavior towards Indigenous Peoples.

- Uses explicit cultural appropriation of Indigenous culture and imagery.

- Deploys capital that infringes on Indigenous land rights.

- Desecrates sacred places.

If any of these issues trigger the screen, the company is automatically excluded from the portfolio.

The second tier applies a more nuanced scoring system. Devised by First Peoples Worldwide, it analyzes corporate policies, supply chain practices, and accountability measures. Through this analysis, a score is assigned to companies for use in further corporate and shareholder engagement. Leading Fortune 500 companies were screened, and a few companies previously unidentified were found to violate Indigenous Peoples’ rights.

One of the most significant challenges to building a dataset of companies to test the screen stems from the invisibility of Indigenous Peoples in country-level data, as well as how corporate actors, policy makers, and even the media report (or lack reporting) about Indigenous Peoples. For example, in a few of the cases researched, impacted Indigenous Peoples were referred to as “communities”. The conflation of “Indigenous Peoples” with “local communities” blurs important distinctions between rights holders and very specific rights. This lack of clarity results in investors receiving suboptimal data about the exposure their portfolios might have to Indigenous Rights Risk.

While the screening tool focuses on Indigenous Peoples' rights, it necessarily holds an intersectional dimension that addresses critical issues such as biodiversity, land tenure, extractive agriculture, and sustainability. Indigenous Peoples have a unique relationship with the environment and share a spiritual, cultural, social, and economic relationship with their ancestral lands. Traditional laws, customs, knowledge and practices reflect both an attachment to land and responsibility for preserving traditional lands for use by future generations. By screening out companies that infringe on the land rights of Indigenous Peoples or that desecrate sacred places, investors are prioritizing corporate behavior that respects the free, prior, and informed consent of Indigenous Peoples, as well as Indigenous-led solutions for environmental preservation and climate change.

“Criteria related to Indigenous rights and impacts to Indigenous Peoples is quickly being recognized by the market as a critical aspect to aligning a portfolio with sustainability and social justice commitments, said Kate R. Finn, Executive Director of First Peoples Worldwide. “Our goal for the Indigenous Rights Risk Screen is to provide the most comprehensive framework to date that accurately assesses a portfolio against Indigenous rights criteria.”

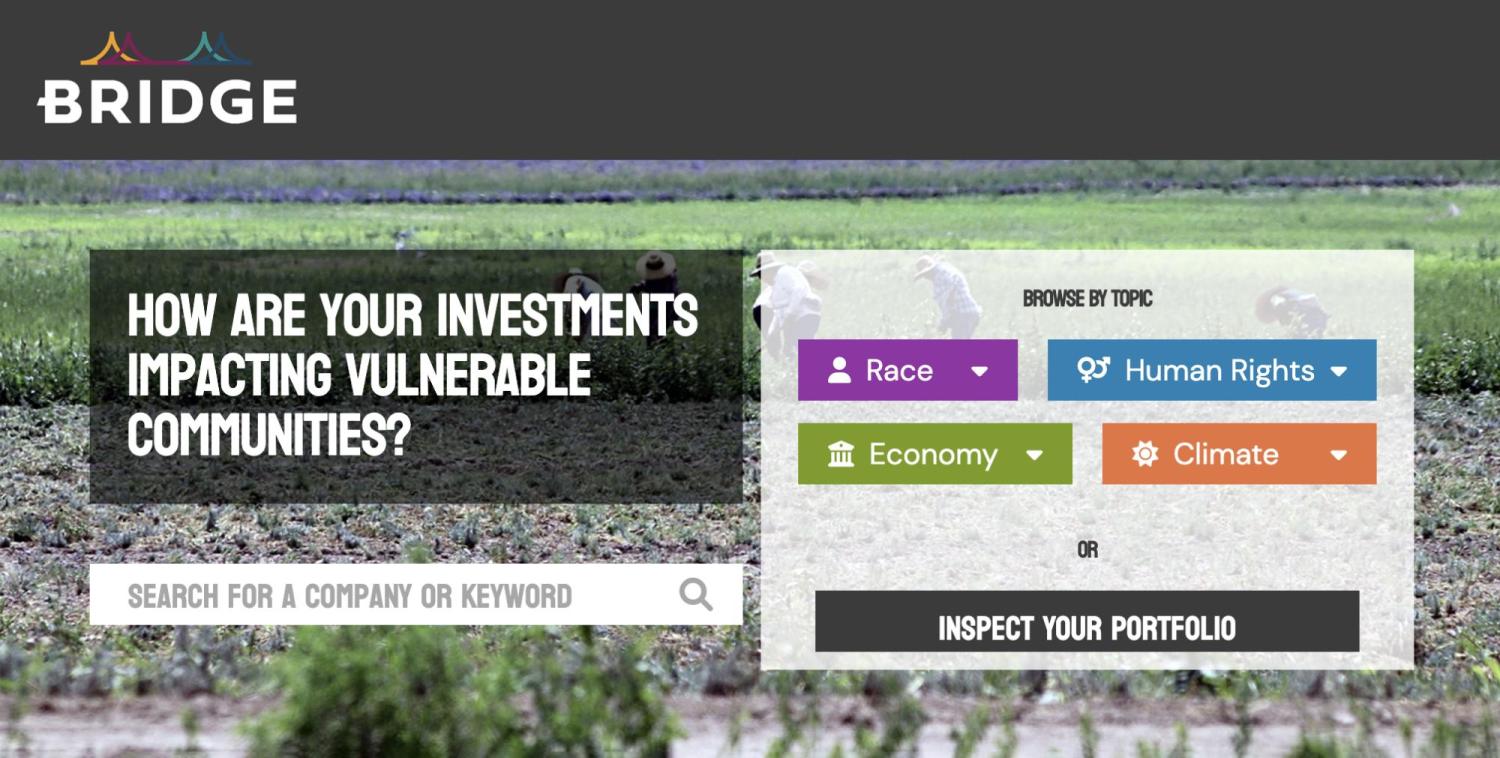

Through BRIDGE–a new platform that helps capture urgent social justice issues for investors–First Peoples Worldwide and Adasina continue to test and measure best practices to integrate a comprehensive view of Indigenous Peoples into investment decisions, in order to both protect the rights of Indigenous Peoples and long-term shareholder value.

“We are grateful for the expertise of First Peoples Worldwide and all of the groups that helped build and continue to develop the foundation for BRIDGE,” said Renee Morgan, Social Justice Director at Adasina Social Capital. “We will continue to work together to understand the best ways to integrate Indigenous Rights Risk and other social risks considerations into an active portfolio.”