The Only Black Man at the Party: Joni Mitchell Enters the Rock Canon

[1] On Halloween of 1976, a week before her thirty-third birthday, singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell strutted into a Los Angeles party in dark pancake makeup and a pimp’s suit and passed for a black man. For the next six years, Mitchell appeared intermittently in this character, whom she named Art Nouveau. On the cover of the December 1977 double-album Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter (DJRD), Art strides confidently into the foreground while the blonde singer frolics behind him. Clever editing of the 1980 concert film Shadows and Light puts Art in Mitchell’s place to close the last verse of “Furry Sings the Blues”—an ironic choice as the lyric portrays the singer as a contemporary white star on a pilgrimage several decades too late to witness black Memphis’s giving birth to the blues. Art’s final appearance in 1982 was in a short film called “The Black Cat in the Black Mouse Socks” in which Mitchell’s character, Paula, attends a costume party in the guise of a black man and meets a former lover there. In “Black Cat,” Art supplemented his makeup and pimp suit with a final accessory: a portable casette player pumping out selections of Miles Davis’s music. “Black Cat” was Mitchell’s contribution to Love, an unreleased Canadian anthology of female-authored films—and Art Nouveau’s unheralded exit from public view. Although Mitchell has not appeared as Art since 1982, the Candian transplant to Los Angeles has shrewdly ventriloquized two positions marked black and male: those of the jazz musician and the street-smart pimp. In this essay, I argue that Joni Mitchell’s black male persona earned her legitimacy and authority in a rock music ideology in which her previous incarnation, white female folksinger, had rendered her either a naïve traditionalist or an unscrupulous panderer.

****

[2] A talented wordsmith, Joni Mitchell was planting a productive pun when she told an interviewer: “The thing is, I came into the business quite feminine. But nobody has had so many battles to wage as me. I had to stand up for my own artistic rights. And it’s probably good for my art ultimately” (Wild 64, my emphasis). True to the possibilities implied in the pun, the more Mitchell has asserted herself as a serious artist, the louder her black male persona, Art, has spoken. Indeed, she has incorporated the figure so fully that she no longer has to don the costume to claim the standpoint. For example, Mitchell chided a Canadian interviewer for refusing to recognize her transition from naïve white female to black auteur: “The white male press present me always in groups of women, you know. They always want to keep me in groups of women. Whereas the black press lumps me in with [Carlos] Santana and Miles [Davis]. They're not afraid of my—they don't have to keep genderizing me” (Porter). While effective in striking many journalists dumb, Mitchell’s invocation of a groundswell of support in black publications was a bluff that succeeded only because rock critics are largely unfamiliar with that archive. For, in actuality, the two articles that put Mitchell in a pantheon with Miles and Santana are both the work of a single author, music journalist Greg Tate (“The Long Run”; “Black and Blond”).

[3] With so small a chorus of black journalistic advocates, Mitchell has had to ventriloquize this purportedly black position herself to advocate for her admission as an “honorary male” in the rock canon (Wild 64). In one oft-cited tale, she reported chastising an unnamed man by informing him that deeming her the best female singer-songwriter was as offensive as calling someone “the best Negro” (Strauss). Couched in that retort, no doubt, was Mitchell’s irritation with the spate of honors she received in the late 1990s. The Grammys, Sweden’s Polar Prize, and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame invariably praised her as first among women in rock, rather than as a leading innovator among all rock musicians. Mitchell’s “best Negro” riposte illustrates that her black pimp persona provided an authoritative position from which to criticize sexism as if it were racism against black men. By presenting herself as a black male victim of racism—a type of discrimination rock mythology deems anathema to the music’s cultural politics—Mitchell ensured that her advocacy for her art exceeded what Lauren Berlant calls a “female complaint,” a plea easily “devalued, marginalized, and [rendered] ineffective in a patriarchal public sphere” (Rose 162).

[4] Rather than speaking as a woman, Mitchell pursued the ingenious but limited strategy of literally and figuratively painting herself as a black male. From this position, she engaged in “homosocial bonding with white men in an attempt to raise [herself] to the status of dominant men in the ruling race” (Ross 64). Given this and other crucial functions fulfilled by her black pimp persona, it becomes less surprising that Mitchell has not relinquished her alter ego. Far from abandoning Art, Mitchell plans to open her still-unfinished autobiography with the unexpected declaration of identity: “I was the only black man at the party” (Strauss). Despite this long career of inhabiting blackness, no one has yet attended to the role her black persona has played in counteracting rock’s tendency to devalue feminized genres and women performers.

[5] This essay, therefore, is the first extensive examination of how a calculated transformation from vulnerable white female folksinger to black pimp-cum-jazz musician won Joni Mitchell entry into the rock canon. While Mitchell’s career is typically portrayed as a successful battle against rock’s entrenched sexism, I tell a story in which manipulations of perceived race and genre were crucial in securing an exception. In recounting Mitchell’s unusual strategy, I revise scholarly conversations about blackface and female masculinity that were not designed to account for such a case. I depict rock’s cultural topography as one in which race, gender, and genre have served as regions with unequal cultural and economic capital (e.g., black music, women’s music). In addition, I demonstrate that rock’s aesthetic ideology does not reflexively move to exclude “women and blacks” on sight. Rather, as it sifts through musical subgenres’ competing sets of aesthetic priorities, “rockism” is capable of taking Joni Mitchell for a man—even a black man—despite the seeming absurdity of such a classification (Wolk). Therefore, in the end, this essay serves as a reminder that—contrary to declarations that honoring Mitchell spelled the end of rock’s sexism—her beating the white rockers at their own game should not be confused with having changed the game.

****

[6] No fan, journalist, or academic has yet connected Joni Mitchell’s turn as a black man to her struggle to evade what rock ideology deemed mutually degrading markers: white, female, folksinger. Before proceeding to an account of Mitchell’s self-refashioning as rock’s ideal black father figure, it is worth taking stock of why this story has not yet been told. Her late 1970s albums, Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter and Mingus (1979), have never benefitted from widespread critical or fan support. The former boasted the aforementioned blackface pose; the latter dove headfirst into jazz fusion after brief flirtations with the style on earlier albums. Mitchell’s development through 1974 had been more or less in sync with the emergence of rock subgenres such as folk-rock, country-rock, and soft rock. However, she veered far from the rock mainstream when she began to cover jazz material, collaborate with jazz musicians, and experiment with song forms and studio technologies. Consequently, the recordings identified as jazz have a smaller audience and receive less discussion than those more easily located within a classic rock spectrum.

[7] However, as one would expect, the most dedicated and informed of her fans—who can be found on the vibrant and voluminous Joni Mitchell Discussion List (JMDL)—have discussed autobiographical lyrics of DJRD and compared the four studio albums from what many now call the jazz period (1974-79). Still, even they have sidestepped discussion of Mitchell’s pimp persona. In the JMDL archives, I have found only one substantive engagement, an eloquent argumentagainst using the term “black face” because Art Nouveau is not a “comic travesty” but rather “an admittedly eclectic homage to [Miles Davis--] one of her musical idols who happened to be Black” (Julius). While correct in distinguishing Mitchell’s full-body bronzing from the burnt cork, white-rimmed eyes, and bright red lips of the minstrel stage, such a defense does not address that a black pimp could be understood as a racial caricature of its own and that Mitchell’s black persona does extensive work beyond paying homage to Miles Davis.

[8] Perhaps animated by the same fear that Mitchell’s masquerade will be taken for racist mockery, musicologists have introduced some inaccuracies in discussing the blackface episode. James Bennighof sanitizes Mitchell’s pimp alter ego, making him “an African-American trickster figure” of unspecified gender and occupation (102). Lloyd Whitesell is very near the mark but also avoids the pimp terminology in calling Art a “dancing, dandified black man” (225, 224, 255n30). From these evasions, it would seem that to acknowledge that Mitchell was interested not in respectable blackness but in its low-down variant would automatically demand full and immediate condemnation. Demonstrating the same trepidation, biographer Karen O’Brien quickly alludes to potential controversy involved in racial impersonation but declines to describe it, offering instead somewhat unrelated praise from Mitchell’s black admirers such as the bassist Charles Mingus and, especially, the aforementioned Greg Tate (173-75). O’Brien is not alone, as reference to Tate has become a standard way for white biographers, journalists, and conference organizers to include a passing mention to Mitchell’s black fans while sequestering any discussion of racial politics from more traditional inquiries into her guitar technique, harmonic sense, lyricism, and influence (especially on younger women). Indeed, the songwriter Sean Nelson is the only published white critic I have found willing to challenge—even humorously skewer—Mitchell’s insistence that she should be recognized as black (115-17).

[9] Very recent publications have begun to investigate the Art persona further, but they are either fragmented or skewed toward celebration. In a new biography, Sheila Weller includes the first interview with one of Mitchell’s boyfriends during the Art Nouveau years, the late percussionist Don Alias. He recounted his concern that her circle of white intimates would think the cover exposed him as a black pimp exploiting a glamorous white star (425-38). Carried by narrative momentum, Weller recounts stories about Mitchell and Alias without much analysis. By contrast, scholar Kevin Fellezs develops a thesis that the Art Nouveau disguise shows “the constructedness of blackness and masculinity” (168). Yet, he says little about the longevity or the limitations of Mitchell’s pimp pose.

[10] Fellezs praises cross-racial and cross-gender impersonation as a manifestation of Mitchell’s attempt to embody the full range of human qualities represented by her “unifying fetish”—a chief’s wheel from an unknown Indian group. Situated at the center of this symbolic circle, the effective chief absorbs qualities from the four major points of the compass and, thereby, “develop[s] the ability to speak a whole truth… to other people” (166). Fellesz reports selectively to portray Mitchell as an anti-essentialist, a maverick whose blending of jazz and rock exemplifies a larger social struggle against segregation by race and gender. Yet, Mitchell has shown that her transcendence of racial boundaries, at least, depends upon others’ upholding their essential functions. For, as she elaborated in the concert filmPainting with Words and Music, Mitchell believes the wheel distributes human qualities by the compass points of a racialized globe. Wisdom is of the North and the white race; heart comes from the soulful blacks of the South. Clarity is the gift of the East’s intelligent yellow race and introspection from the spiritual red men of the West (Fellezs 166; Tosoni). Certainly, it would be difficult to find more predictable modern racial tropes than a body/mind split along a black/white axis, a mystical Oriental, and spiritual red man. In this racialized distribution of virtues, it would appear that only chiefs and artists, such as Mitchell, are able to obtain qualities from outside their own race’s store. Everyday people remain stuck with the gifts and limitations of their racial cohort. In contrast to Fellezs’s celebratory reading, Mitchell in blackface drag acquires a reputation for artistic daring and psychological complexity by impersonating a black pimp figure who accrues neither.

****

[11] Perspectives honed in the last two decades of work on blackface and on female masculinity could help to render Mitchell’s under-analyzed performance visible and assess its significance. I stage a dialogue between these two fields that revises both. For, if Eric Lott’s classic Love and Theft brings the male homoerotic aspects of nineteenth-century blackface to view, it does not prepare us to discuss a white woman performing in the wake of the civil rights movement. Similarly, the feminist concept of immasculation and queer theoretical interest in female masculinity do not yet account for the ways in which the racial location of spectators and performers (as much as patriarchy and heteronormativity) affects how gender is enacted and identified. A straight white woman arriving at the end of legal segregation and indulging in racial impersonation to counteract gender bias, Joni Mitchell offers the opportunity for a new synthesis in studies of blackface and trans-gender performance.

Circa 1967: Mitchell Arrives; Rock Loses Roll, Women, Blacks

[12] To borrow a phrase from Carole King, astute members of the first generation of rock critics felt the earth move under their feet in 1967. Writing the very next summer, Ellen Willis pinpointed what “the Beatles (with a lot of help from Bob Dylan)” had wrought on the popular music scene (“Records: Rock, Etc.” 420-21). In her narrative, the summer 1967 release of the Beatles’ high-concept masterpiece,Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, drew a line in the sand: in the early 60s, Chuck Berry and The Beatles were writing catchy musical hooks that were musically innovative and irresistible to dancers and record buyers. Yet, in the wake of Sgt. Pepper, Willis observed the rise of a “bohemian” contingent intent on evaluating rock in terms of a highbrow opposition between “art and Mammon” (420). In 1970, Patricia Kennealy-Morrison concurred in her own reflections on how “rock’n’roll became rock.” Though she did not cite Pepper, she identified 1967 as the year male fans who had been “lying low listening to folk or jazz or blues… came to rock in open and significant numbers” because the music had become “more intelligent” (358). Thenceforth, rock would have a full-fledged intellectual class, absorbing full LPs in rapt concentration, far from scenes of dancing or screaming fans. These two writers, among the few women publishing on rock in its infancy, were eyewitnesses to an effort to lift the young genre to the classicized, academic status that jazz attained before it.

[13] Whether one begins the story of rock’n’roll with Ike Turner in 1951 or with Chuck Berry, Elvis, and Buddy Holly in the middle 1950s, the look and sound of the genre were significantly different by the latter part of the next decade. With the rise of rock (sans roll) as art music, dance was subordinated to intellection, and white women and black people of both sexes were maligned, sublimated, or sidelined (Echols, “Shaky Ground”; Wald 230–54). Girl groups, women soloists, screaming teenyboppers, and the buoyant heartthrobs they desired had mostly been bustled from the center of a rock scene that had, at that time, the largest market share of any genre (Coates). Rock’s newly ascendant cult of the auteur disdained mainstream pop stars as panderers, robbed of masculine creativity by middlebrow handlers at whose insistence they produced diluted versions of black originals. If black men could be called upon as ghostly mentors or sidemen injecting soul, classic rock formations rarely had a place for women of any color.

[14] At the cusp of this reorganization, in 1965, Roberta Joan Anderson, hailing from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, began gigging across the border in Detroit as part of the husband-wife duo Chuck and Joni Mitchell (O’Brien 28). The Mitchells’ repertoire consisted of folk songs, especially English Child ballads. When rock was losing its roll in 1967, twenty-three year-old Joni Mitchell was shedding a husband who she said “controlled the purse strings” and discouraged her efforts to compose original songs (Lacy and Bennett 8:25). Although the adolescent Mitchell had enjoyed dancing to Chuck Berry, Elvis, and Little Richard in Saskatoon, the woman who immigrated to the United States was identified as a folk singer. She recalled:

When I first came out, I appeared to be a spinoff of something that was going out of vogue, which was like a poor man's Baez or Judy Collins. The old thing was folk, and the new thing was folk rock. Nobody wanted to sign me, because I appeared to be part of this old thing that was dying, but musicians could see that I was a musician (Wild 64).

[15] Although Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and Judy Collins made both the style and the politics of rural protest marketable in the first half of the 1960s, Dylan turned away from folk’s rusticity toward an urban bohemianism—or from folk’s common repertoire to rock’s investment in individual authorship. These changes were heralded by his famous use of electric instruments at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. With that festival, folk-rock superseded folk. This hybrid was short-lived, however, lasting only until 1966, when its practitioners dropped the “folk-“ prefix to achieve, what critic Paul Nelson called “maturity in thedark and manly art of rock and roll”—or, more accurately, rock without the roll (216, my emphasis). As Nelson’s epithet illustrates, folksinger Joni Mitchell was located in a genre that was seen as—if not racially white—then certainly light, trivial, and feminine. Worse for her prospects, folk was no longer seen as marketable. While cognoscenti in the coffeehouses formed the economic base of acoustic folk, the record industry would prove more interested in an audience that would fill stadia to listen to amplified rock. For, even though some consumers still bought music marketed as folk, the industry designated rock a youth music and, as such, a site for innovation rather than nostalgia.

[16] Thus, even though other artists were having hits with her compositions, Mitchell could not secure a record deal while laboring under the title of folksinger during her first two years in the U.S. When she finally released her self-titled album of original songs in March of 1968 (also known as Song to a Seagull), Judy Collins, Tom Rush, and Buffy St. Marie had already charted with her compositions “Both Sides Now,” “Urge for Going,” and “The Circle Game,” respectively. No songs from Mitchell’s debut matched the chart success of these other artists. In 1968, a new folksinger was already nearly past her sell-by date. Yet while, the tendency to identify her music as “delicate” or “mythical” (Beker) classed her with fading folk romanticists rather than commercially viable rock modernists (Keightley 135-37), it also positioned her in an elevated but exposed position in relation to her sex.

1968-72: 90% Virgin, 10% Whore

[17] With a simple part down the middle of her otherwise unstyled, straight, blonde hair, her unfitted dresses draped over the young person’s uniform of casual jeans, Joni Mitchell arrived on the US-music scene in 1967 as a avatar of folk’s anti-bourgeois aesthetics. Her music was unclluttered; listeners could imagine they were overhearing her private thoughts as her birdlike soprano played against the sole accompaniment of her guitar, dulcimer, or piano. The resulting gender and genre categorization girl/folksinger positioned Mitchell as the fulfillment of a nostalgic dream for a time and place before the fall into the vices of urban, commercial society. For rock’s newly ascendant bohemians at Rolling Stone, Creem, andCrawdaddy, a light-voiced soprano with a guitar, singing neo-pastoral ballads of kings and ladies, pirates, castles, and magic conjured imaginary times and places where heroic individuals could rise above the muck of the marketplace. An extensive profile expounds on the themes of early coverage of Mitchell: Time magazine referred to her as a “freckle-faced girl with straight waist-long blonde hair who doesn’t seem to care about her new wealth.” This reading of her appearance was a fitting counterpart to the interpretation of her sound, a “fluty, vanilla-fresh voice with a haunting, pastoral quality.” The spartan instrumentation and introverted voice communicated “a country girl's cool-eyed reaction to urban life” (“Into the Pain of the Heart”).

[18] In accordance with that figure’s remote origins, the pretty blonde Mitchell’s presumed rural innocence of sexual or monetary exchange served to increase her value, quicken desire for her, and hasten her eventual fall. The very value historically accorded to unsullied white femininity as a potentially exclusive white male possession stoked interest in Mitchell’s romantic exploits. Following the colors of that “vanilla-fresh” voice, others framed Mitchell as the “White Goddess of mythology…, elusive, virginal and not a little awe-inspiring” (Watts). By contrast, women rendered black by their association with R&B, such as Tina Turner or Janis Joplin, were more likely to be cast not as goddesses but as disposable sex partners or “scratch-your-back, tiger-lady, stone-soul fuck[s]” (Kennealy-Morrison 361). Historian Stuart Henderson offers an incisive analysis of the sexual innuendo of Reprise Records’ advertising campaign for Joni Mitchell’s second album, 1969’s Clouds, observing that the stark ads—“Joni Mitchell is 90% virgin,” “Joni Mitchell Takes Forever,” and “Joni Mitchell Finally Comes Across”—offered sexual access to the artist (Henderson 94–96). It is important to note, as well, that Reprise specifically equated sexual access to Mitchell’s body with purchase of the LP. This equivalence constitutes what Diane Cady would call a contemporary “medievalism”—a redeployment of the premodern conceit that women and money share an essential nature that renders each “[item] of exchange” the name for the other as both circulate “in the sexual and economic realms” (29, 27).

[19] Participating in this alchemical imagination, consumers could not get sex with the artist through the LP but did seek at least voyeuristic access to her sex life through hearing Mitchell’s albums. They treated her recordings as pure (if oblique) confessions, scouring her lyrics for clues to her known love affairs with male stars from Graham Nash to James Taylor. Taking this obsession to its ugly conclusion, Rolling Stone produced two items that are now infamous in Joni Mitchell lore. In February of 1971, the magazine presented Mitchell with the dubious title of “Old Lady of the Year [1970].” Both Henderson and Alice Echols rightly interpret this incident as evidence of a sexual double standard, unfairly shaming Mitchell for behaving like a “traveling woman” when her male counterparts were trying to live up to the myth of the rambling bluesman (Morrissey). One year later,Rolling Stone portrayed Mitchell as a heartbreaking coquette. The February 3, 1972 issue graphed the relationships linking all the names in the “Blue Book of LA Rock.” The tree branched off into performers and businessmen at each record label. Every name appeared in plain type, except Joni Mitchell’s, which appeared in the center of a gigantic lipstick imprint, with the phrase “kiss kiss” projecting in all directions. While her male colleagues were linked by virtue of musical or business interests, the lines connecting Mitchell to men were—with a few exceptions—decorated with broken hearts. Outraged and ashamed when her disapproving mother heard of her daughter’s reputation for looseness, Mitchell refused to grant rock’s premiere magazine interviews for nearly ten years (Echols, “The Soul of a Martian” 210). This context helps explain Mitchell’s subsequent shift to musical and poetic techniques that blocked intimate access. What rock ideology did not foresee, however, were the ways she revealed and embodied their conjoined racial and sexual fantasies when she re-emerged as a black pimp.

1974-present: Black Male Armor

[20] After humiliation in the pages of Rolling Stone, Mitchell sought protection against exposure and exploitation—the costs of the high value accorded to the commodity of rock music and to white womanhood. In 1971, fellow songwriter Kris Kristofferson listened to the spare, acoustic revelations of Blue and admonished Mitchell, “Save something for yourself” (Smith 51; Mercer 25). A few years later, Mitchell was headlining a full-sized electric jazz-rock band and producing far fewer songs in the so-called confessional mode. Asked if these divergences would cause her to “lose” the vulnerability that had endeared her to audiences, Joni gave interviewer Malka Maron a laughing retort: “I don’t want to be vulnerable anymore!” (Lacy and Bennett 55:20). Her reinvention as a pimp-outfitted jazz musician effectively counteracted the devaluation of her gender and genre that resulted from the rock ideology that emerged in 1967. The racial and gendered specificity of rock’s aesthetic imagination necessitated that her transformation into a virtual male occurred through resituating herself in the fields of race and musical genre.

[21] To use one of her favorite metaphors, one might say that over the course of the 1970s, Joni Mitchell took flight from critics and the buying public. Her 1972 album For the Roses spawned her first radio hit, a song that purposely beefed up her austere style and substituted sly double-entendre for the melancholy lyrics that had made her a cult favorite. Featuring a full rhythm section, backing her guitar in the popular country-rock style, “You Turn Me On, I’m a Radio” reached #25 on the billboard Hot 100 chart in February of 1973. Mitchell’s next album, Court and Spark (1974), produced the top seven hit “Help Me,” and its follow-up, “Free Man in Paris,” which rose to #22. Even more important, in a rock industry dominated by the artistic and economic unit of the LP, Court and Spark stayed at #2 on the US album charts for four weeks and sold five hundred thousand copies a little more than a month after its release. Although her next three albums also attained Gold Status (sales of 500,000), they did not yield any hit singles. The popular and critical consensus celebrating Courtsplintered as Mitchell altered her style drastically. Her departure from autobiographical lyrics performed in acoustic or soft rock modes left many critics puzzled and fans cold. It is unclear whether Mitchell sought privacy and sabotaged her popularity or, instead, made a calculated bid to convert popularity into critical acclaim. However, the black pimp persona that emerged at this time served as an emblem of changes in her lyrical persona, melodic and harmonic sense, and orchestration.

****

[22] Art Nouveau was born when Joni Mitchell assumed the spirit of a black pimp who passed her on an LA street and intoned a compliment edging into a come-on. Recalling autumn of 1976, she told Angela LaGreca:

I was walking down Hollywood Boulevard, in search of a costume for a Halloween party when I saw this black guy with a beautiful spirit walking with a bop… As he went by me he turned around and said, “Ummmm, mmm… looking good sister, lookin' good!” Well I just felt so good after he said that. It was as if this spirit went into me. So I started walking like him. I bought a black wig, I bought sideburns, a moustache. I bought some pancake makeup. It was like ‘I’m goin' as him!’

A self-authorized sexual predator, beholden to no sexual double standard, strolling the street with a bopping walk that could not but call to mind the jazz genre, Art Nouveau would seem the perfect vehicle to flee from the vulnerability and devaluation that marked the white female folksinger.

[23] In referring to the influential European artistic movement, the name Art Nouveau recalled Mitchell’s lifelong passion for painting. Just as this style created a bridge between neoclassicism and modernism in the visual arts, so did “Art Nouveau” signify musicaldepartures for Mitchell. From this point on, she would include an increasing number of songs that eschewed what she called her grand theme: “Where is my mate? Where is my mate?” (Mercer 185). Some would be told by male narrators; others were esoteric musings or pointed criticisms of politicians and businessmen. Mitchell all but stopped appearing onstage alone, criss-crossing the stage to accompany herself at the acoustic piano, guitar, or dulcimer. From 1973 onward, her voice and guitar (or piano) led a band of male musicians, beginning with the multi-generic specialists of the LA Express and culminating with the architects of electronic jazz such as Pat Metheny, Jaco Pastorius, and alumni of Miles Davis’s bands—Herbie Hancock, Don Alias, and Wayne Shorter. As a result, Mitchell’s style diverged from acoustic folk—even from folk-rock—and gravitated toward the electrified hybrid known as jazz-rock or, more commonly, fusion.

****

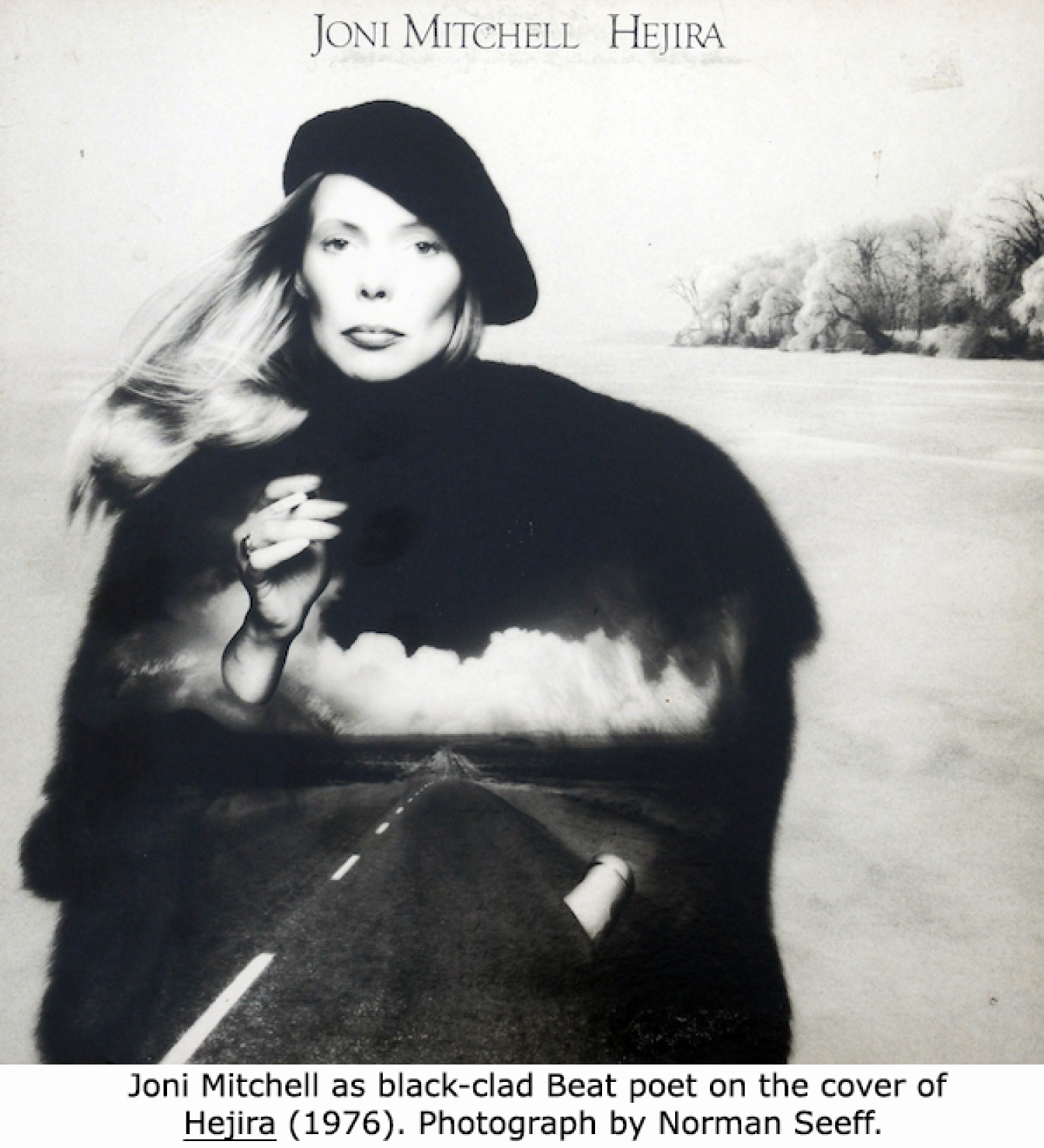

[24] Visual counterparts of these sonic changes, the album covers of 1976-79 strongly hinted at a masculinized Mitchell, recolored black.Hejira (1976) depicted her with a cigarette and a black beret, placing her in the orbit of the bebop-inspired Beat poets, on the road like Jack Kerouac (Figure 1). Despite Mitchell’s avowed dislike of Beat poetry, she shared their wanderlust, anti-establishment cynicism, and deep investments in jazz music and black people as reservoirs of the physicality and spontaneity that whites lost as they traded manual labor and rural or urban community life for intellectual labor and suburban isolation (Mercer 178; Baldwin 297-98; Roediger, 95-6). On the inside flap of the LP (Figure 2), she skates away from the viewer, like the protagonist of “River,” the classic song from her “vulnerable” Blue period (1971). Yet, where the cover of Bluefeatures a close-up of Mitchell’s white face, she faces away from the viewer on the back of Hejira, her black flowing garments rendering her in the shape of that album’s “Black Crow.” The black bird would turn out to be an intermediate figure in Mitchell’s transition from white woman to black man.

[25] The elements of Mitchell’s self-refashioning on the Hejira coverreceived even more explicit figuration on its successor, the aforementioned Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter (1977). Some do not recognize the figure in the foreground as Mitchell in blackface drag (Figure 3). Even those who do tend to be flummoxed. This perplexity is understandable as the precise relationship between the blonde and the black is difficult to pin down. (I should note, I omit discussion of the boy on the cover because I consider him part of another story in the expansive, associative dream logic that the album’s “disparate” songs and pastiche cover convey [Whitesell 220]). Joni Mitchell and her unlikely doppelgänger are more than unrelated symbols of opposition. The economic, erotic, and artistic history and hierarchy depicted shift like the images in a kaleidoscope, with a slight rotation of perspective.

[26] If one takes Art to be the titular Don Juan, then Mitchell is, at best, his copy. The singer’s notorious, wandering lust becomes not a character flaw but a legitimate birthright inherited from this father figure. In music, too, she might appear the daughter, a folksinger belatedly encountering African diasporic rhythms, tones, language, and timbres, layering these sounds over her compositions like so many coats of brown pancake makeup. As a pimp, the black figure might appear to have authority over a blonde whose modest clothing covers her own flesh, yet emphasizes sex—emblazoned, as it is, with a female nude. Yet, a different interpretive approach confounds any sense of black male pre-eminence. The blonde Mitchell and the black pimp seem less father and daughter than fraternal twins. They appear to be roughly the same age; her white skin in black clothing (a motif carried forward from Hejira) is a perfect companion to his black skin encased in white clothing. Viewed from yet another perspective, the white woman dominates. The blonde-in-black may be wearing a magician’s cap and releasing white doves from the fabric of her black dress (cf. Whitesell 224). The pimp’s white vest and suitcoat—as well as his angled shoulders—liken him to these doves in flight, suggesting that he might not be her progenitor but, rather, a product of her magical creativity. Though in the background, the blonde-in-black may be the matrix that generates both black and white life, including the grounded street hustler and the white chick—bird or woman—in flight. There is no way to arrest the instability of the Art and Joni pairing or its musical, economic, and political meanings. In fact, precisely because of its unruliness, the pairing has been tremendously useful to Mitchell in her quest for protection and prestige in an art economy shaped by mutually constituting forms of racial and gendered value.

****

[27] Though as far back as Ladies of the Canyon (1970), Joni Mitchell employed jazz musicians to add instrumental obbligatos to her albums, the debut of Art Nouveau in 1977 signaled a high-water mark of these engagements. After the release of DJRD jazz bassist and composer Charles Mingus contacted her to give voice to the last melodies he wrote before amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) incapacitated him. Mingus did not seek one of the many singer-lyricists more firmly rooted in jazz, such as Betty Carter, Eddie Jefferson, or Mitchell’s own adolescent inspirations, Annie Ross and Jon Hendricks. Given Mingus’s use of jazz as an explicitly pro-black artistic and political statement, his collaboration with Mitchell could be interpreted as granting her honorary blackness.

[28] In 1988, she spoke as if that blackness were a social fact. An interviewer asked if Mitchell had been drawn to work with Mingus because he was black. Reversing his presumption, she chided “No,my blackness was a part of it actually because I appeared on the cover of Don Juan's Reckless Daughter as a black man. Charles thought I had a lot of audacity to do that and that was one of the reasons he sent for me” (Sutcliffe). Despite Mitchell’s best efforts, this insistence on spiritual and musical blackness has concealed but not eliminated the gender barricade that rock placed in her way. It is especially intriguing, then, that gender resurfaced in the same interview in an alternate account Mitchell offered of the genesis of Art Nouveau.

[29] Reflecting on the 1976 Rolling Thunder Revue, she recalled her costars’ stage makeup and their crusade: “Bobby [Dylan] and Joan Baez were in whiteface and they were going to rescue Hurricane Carter.” The famous subject of Dylan’s anthem, “Hurricane,” Rubin Carter was a successful black boxer whom the state of New Jersey had falsely imprisoned for murder. Although Carter had become acause célèbre, Mitchell was unimpressed:

I had talked to Hurricane on the phone several times and I was alone in perceiving that he was a violent person and an opportunist. I thought, Oh my God, we're a bunch of white patsy liberals. This is a bad person. He's fakin' it. So when we got to the last show, which was at Madison Square Garden, Joan Baez asked me to introduce Muhammad Ali. I was in a particularly cynical mood—it had been a difficult excursion. I said, Fine, what I'll say is—and I never would've—I'll say, We're here tonight on behalf of one jive-ass nigger who could have been champion of the world and I'd like to introduce you to another one who is. She stared at me, and immediately removed me from this introductory role. I thought then, I should go on in blackface tonight. Anyway, Hurricane was released and the next day he brutally beat up this woman…. (Sutcliffe, ellipsis in original).

If, to Mitchell, Dylan and Baez were performing in apologetic whiteface and being suckered by a slick black hustler, then she—who could detect a black hustler’s “jive” bullshit—should have appeared in blackface to signify her exemption from the white patsy’s gullibility (Yaffe). In this retelling, Mitchell highlights the act of racial ventriloquism, her fantasy of calling a black man—heavyweight champion and Black Muslim Muhammad Ali, no less!—a “jive-ass nigger” to his face. Yet, the unvoiced aspect of this narrative is notthe classic white male rocker’s desire for brotherhood with black men (den Tandt). The concluding ellipsis marks an incomplete wish for an interracial sisterhood that could prevent, interrupt, or avenge men’s violence against women. Mitchell wanted to be black in this case not (only) to play the dozens with black men but to speak, as a woman, about a premonition of gendered violence.

****

[30] The feminist critique of intimate violence embedded in Mitchell’s attraction to blackface was all but erased as Mitchell and her interlocutors attended to her new star aura(lity). This term—my extension of Richard Dyer’s useful concept of the (film) “star image” (2)—references the synaesthetic collision of the visual aura and sonic information that is the fan’s conception of the music star. In Mitchell’s case, her new aura(lity) would be that of the overlooked and undervalued black male musical genius. Everything from the unusual tuning system she has employed to her unique sense of harmonic motion has now been framed in that comparative context.

[31] A black Joni Mitchell has bested her rivals and critics in the rock field because of the unique positioning of black music in its ideology. Black blues recordings were one of the primary models for the classic rock style of everyone from the Beatles and Bob Dylan to Eric Clapton and Led Zeppelin. Through Art Nouveau, Mitchell instead aligned herself with jazz, another black-associated genre, which Mitchell and others understood as “black classical music” with more harmonic and formal variation than black folk-blues (Mitchell). She participated in a trend I mentioned before, what Ellen Willis identified as the aspiration of rock to the status of jazz or poetry. Outside the youth culture, jazz had become an adult music by the time Mitchell arrived on the scene in 1967. In that economy, rock was positioned behind or beneath jazz as a developed art form. Mitchell’s fuller entry into the genre of jazz after 1973 cost her fans and her connection to a youth-driven industry. Yet, to compensate for these losses, she did absorb some of jazz’s aura of maturity and sophistication—ironically, to wield against rock in prying open the doors of its resistant canon.

[32] Scolded and ostracized from the beginning of her career by some folk and rock musicians for her alternate guitar tunings, Mitchell can now boast that “only jazz musicians” have been able to play her “weird chords” (Himes). That she had to solicit jazz musicians to play her music bears out her claim that her music was always more sophisticated than folk—and even rock—whose critical establishment often derided her as a girl writing private confessions in a weak and outdated genre. By her testimony, Mitchell had been a “girl” who got into folk-singing because she could easily become proficient enough to play coffeehouses and earn cigarette money. She once quipped: “I entered the arena as a folk musician and all these years later, I still get called a folk musician, but that's not where my roots are. In less than six months, I was a professional folk singer. That's how easy it is to cop those chops” (Morse). In this narrative, Mitchell’s alliance with jazz comes as a foregone conclusion: she intuitively stumbled into its esoteric harmonic realm; her musical colleagues in folk and rock simply took a while to recognize that she had been misplaced in folk. Amateur confessionalism could be set aside for the stringent standards of virtuosity and innovation associated with avant-garde jazz. Playing with jazz virtuosos and speaking from the vantage point of a discounted black musical genius, Mitchell traded popularity for prestige. Art Nouveau was the representative of that exchange.

[33] A major impediment to Mitchell’s insistence on her musical blackness would be the wide distance between her folk-style vocal production and that of blues and jazz singers. From the “fluty, vanilla-fresh” beginning and even through the Art Nouveau years, Mitchell never had the timbres, inflections, or dynamic power that one associates with black standard-bearers in blues or jazz. She has, however, shrewdly reinterpreted this obvious detraction from her claims to black musicality as proof of her kinship with jazz innovators: “the universal rock & roll dialect is Southern black… It's as affected as opera. Hardly anyone sings in their real voice” (Echols, “The Soul of a Martian” 218). In saying she adheres to jazz’s imperative to be original even while arguably failing to perform the music idiomatically, Mitchell deems herself a truer adherent of black cultural principles than are white counterparts who, she alleges, are merely more accurate mimics.

[34] Mitchell has been so successful in these campaigns that those urging her canonization have indirectly consented to her racial reclassification. For example, the journalist Stephen Holden helped promulgate the idea that honoring Mitchell could serve not only as atonement for rock’s devaluation of women but also as an instance of multi-racial inclusion. In chastising the Rock Hall of Fame, Holden highlighted Mitchell’s collaborations across racialized genres—a credential that has played into nearly every major honor since. Echoing Alice Echols, he gave Mitchell credit for innovations usually attributed to the 1980s work of Sting and Paul Simon: “Musically, Ms. Mitchell was a pioneer in the exploration of jazz and African drumming within a folk-rock context” (Holden). The Joni Mitchell Symposium at McGill University was convened by Lloyd Whitesell, who proclaimed that “only Joni Mitchell can bring together Latin percussion, classical orchestra and an array of musical dialects, from British folk ballads to blues, rock and jazz fusion” (Popple, my emphasis). The Grammy Awards invoked this meme to fete Mitchell as “a powerful influence on all artists who embrace diversity, imagination and integrity” (“Joni Mitchell Made a Companion of the Order,” my emphasis).

[35] Given the conviction that artistic integrity dissolves in commerce, it is unsurprising to see imagination and integrity linked; however, the assertion that the artist can find both of those in cross-cultural exploration indicates the emergence of a reformed white identity, declaring itself disconnected from racism. If in most minds rock still remains a white genre, then honoring Mitchell has allowed whites in rock culture to speak in a “register of disaffiliation from white supremacist practices and discourses” (Wiegman 150). Of course, no one seriously takes Joni Mitchell for a black man out of costume. Rock fans, critics, and institutions really deem her an exemplary, post-racist white person—and designate themselves the same for celebrating her.

[36] The story stands at this point today, with Mitchell canonized as both a rare female innovator in rock and as a surrogate black man—and yet, as neither. For, as the debate on sexism and racism in today’s rock criticism indicates, rock ideology still holds aesthetic values that tend to exclude or diminish female singers, popular singles, and contemporary black dance musics (Sanneh). To the lineage of Great Men Mitchell has invoked—Rachmaninoff, Davis, Hendrix, Santana—Mitchell has simply been added as a rare Great Woman in drag. To address this problem with the canon, honoring Bonnie Raitt, Laura Nyro, or Nona Hendryx could lead to a reconsideration of the influence of black women, singers of all backgrounds, dance music, collaboration, and erotic exchanges. The argument here is not that Mitchell is undeserving, but that honoring her as a virtual black man merely reinscribes a white male fantasy of alternately absorbing and transcending the primal qualities of the negro. Attending to a different set of performers could then generate different questions to bring back to the examination of someone like Mitchell. In the space remaining, I would like to set out a few new directions for the scholarly study of blackface, female masculinity, and the Sexual Revolution.

Future Directions for Blackface and Female Masculinity

[37] Two decades of work on blackface from within “whiteness studies” have diffused scholarly (though not popular) anxiety that the mere use of the term blackface must end in comdemnation. While Eric Lott’s economical title has become an indispensible citation, “love and theft” do not serve as adequate synonyms for all the tensions he traces. For instance, he identifies “a dialectic of misrecognition and identification” at work in the relationship between white minstrel performers and spectators, on the one hand, and black men, on the other (152). While identification might be glossed as “love” (among other possibilities), misrecognition cannot easily be classed under the economic umbrella of “theft.” In another moment, the polar structure of love and theft becomes triangular when he writes that “ridicule” served to dissipate “attraction or fear” (123, my emphasis). Again, attraction falls under love but fear seems to introduce a third term in addition to theft.

[38] Lott’s work deserves its towering place, but its key terms should be reconsidered when one departs from the nineteenth-century and the all-male milieu on which he focused. In the case of Joni Mitchell, the “homosexual-homosocial” pattern of white men’s imaginary relationship to black men before the Civil War does not account for the actions of a heterosexual white female celebrity after the dismantling of legal segregation (Lott 86). Her turn as a black man protected her from sexual innuendo, raised her artistic standing, and would appear devoid of “fear” or “ridicule” (123). Identificatory “love” is in place—as is a copyright system in which unwritten black music is ripe for theft—but Mitchell’s story revises Lott’s all-male antebellum framework and points to a different symbolic and financial economy.

****

[39] Roughly contemporaneous with Mitchell’s sex-change, Judith Fetterley used the term immasculation to describe the process of the female reader’s alienating journey through a male-dominated American literary canon. If Mitchell celebrated the addition of “dark and manly” rock style to her light and girlish folk repertoire, Fetterley saw a woman’s incorporation of a masculine perspective as self-negating: “intellectually male, sexually female, one is in effect no one, nowhere, immasculated” (Fetterley xiii, xx-xxii). While immasculation helps explain the canonical imperative to cite male influences while denigrating female counterparts, a strict application of Fetterley’s terms does not account for the means of racial transformation used to effect Mitchell’s sexual transition. Mitchell’s case straddles opposing wishes in the academy’s “identity knowledges”—to unearth and celebrate “women,” and to displace “whiteness” (Wiegman)—and opens avenues of inquiry into scholars’ desires and wishes for the identities they inhabit and study. Is it really more righteous to want to preserve female consciousness but destroy white consciousness? Does the dissolution of either one produce less pain at the individual level—or more good at the social level?

[40] Judith/Jack Halberstam’s deservedly influential exploration of lesbian butchness brilliantly upended Fetterley’s depiction of “female masculinity” as inherently anti-feminist. However Halberstam’s model was not built to account for Mitchell and Art Nouveau, as it dismisses heterosexual women’s masculinity and does not consider race to be fundamental in the performance and perception of gender. Halberstam’s focus on butch lesbians stages a dyadic conflict between men—who enjoy “a naturalized relation between maleness and power” (2)—and lesbian rivals whose “excessive masculinity” poses the greatest threat to male authority and sexual reproduction (28). As Halberstam admits, heterosexual female masculinity fades from view after she deems it too “tame” and “acceptable” to merit extensive consideration (28). Though a serial, heterosexual monogamist like Mitchell could not register in Halberstam’s model, her mode of summoning and dismissing male lovers/muses did not strike these paramours as unthreatening. As Don Alias recalled, when he left during one of her projects to rehearse his own band, she gave him twenty-four hours to remove his things permanently from their shared apartment. He is not the only of Mitchell’s exes to say “it was like a guy breaking up. It really hurt the hell out of me!” (Weller 435). Mitchell’s confrontations with her disapproving mother and hurt ex-lovers—as well as the infamous Rolling Stone pieces—suggest some of the serious disruptions to male authority and female propriety that resulted from this straight woman’s assumption of men’s artistic, economic, and sexual prerogatives.

[41] In addition to demonstrating the need to consider straight women’s masculinity, Mitchell’s masquerade confirms but entangles the distinctions in Halberstam’s taxonomy of drag king styles—by virtue of its cross-racial nature. Halberstam identifies white kings as more likely to engage in irony and parody of male masculinity while black and Latina kings are more invested in seizing masculine sexual bravado by passing as “real” men (242-56). Though a white woman, Mitchell does not seem to be engaged in parody on the DJRD cover: the Don Juan figure is arguably a caricature, but Mitchell does not peek out from beneath him to create an ironic distance between blonde and black man. Mitchell also complicates Halberstam’s observation that nonwhite drag kings tend to do something, to dance or rap, while white ones more subtly strike the subversive pose of a male icon (248, 257). Mitchell’s costume indicates preparation for portraiture, but his strut and outstretched hand suggest an inability to sit still. If, one the one hand, nonwhite drag performers’ aspirations toward realness are attempts to achieve a state of being, then any detectable performance amounts to ostentation—artifice in excess of the natural. Art Nouveau—both cool and in motion—confounds Halberstam’s distribution of race, gender, and performative energy.

[42] The conundrum, then, is why in this performance-based theoretical framework, it has been nevertheless difficult to see the fabled original of street black masculinity as itself a carefully prepared performance of curated language, meticulous afro coiffure, sartorial layering, and jewelry. Somehow, Halberstam designates black female enactments of masculinity as “unperformed,” despite the fact that those outside the lesbian bar (and some inside it) respond to them as ostentatious—even menacing (246). This distinction is somewhat curious, especially considering that one could argue that a black woman flexing muscles, dancing, or rapping packs more of an affective punch than a white one taking up the introverted style of a strong silent John Wayne, or the still brooding of a James Dean (246). Of course, anything that has social meaning is performative; there is no less or more. Thus, the question remains: in what frameworks do black styles seem to constitute the real, and what work is accomplished by designating blackness as unperformed? More cases of cross-racial drag and more sustained analysis will have to speak to an interesting contradiction: black masculinities can seem equally natural when they are aloof as when they are in artistic or erotic engagement with others. It would seem that the presumed realness of black masculinity—and its commutation to black women who are rarely understood as truly feminine—would not simply add to Halberstam’s taxonomy but change our view of the process of gender performance and of the naturalized thinking about race sometimes brought to it.

[43] To reorient the discussion on female masculinity, one could recall Hortense Spillers’s galvanizing insight that slavery’s still-unremedied violations have thrown “customary aspects of sexuality, including ‘reproduction’ [and] ‘motherhood’ into crisis,” rendering black women, in particular, as “ungendered” (221, 222). In Spillers’s wake, others have concluded that proper gender itself might be considered “white property” (Broeck). To incorporate Spillers’s theory into the study of female masculinity would enable investigation of women’s differential access to masculinity—that is, the gendering of racial groups, classes, religions, and other social divisions. In the case of rock’s notorious sexism, it would offer insight into how rock ideology can think of Big Mama Thornton’s masculine edge as natural and unremarkable while Joni Mitchell’s has been received as a miraculous, self-transcending reinvention. One important gain would be the opportunity to continue thinking of what it means that the radical feminist call to undo gender has never had as much resonance among black women whose access to the mixed blessings of patriarchal protection has never been secure. Must one project be understood as necessarily lagging behind the other in terms of temporality or the evolution of radical feminist consciousness? Are the projects of respectability and subversion mere inversions, or are they funhouse refractions that occur as gender moves across a racially uneven field? If race and gender cannot be discussed apart, neither can they be rendered equivalent or parallel. Gender may not always be the fundamental problem or prison. Indeed, the experience of gender confinement as an isolated force may be a mixed blessing of membership in a superior racial caste.

Coda

[44] In a 2004 lecture at McGill University, Jennifer Rycenga set in motion a new trend in academic studies of Joni Mitchell, arguing that the singer’s compositions provide a rare “sonic document” of the effects of the sexual revolution, including the fitful emergence of a woman who could prosper while being no man’s “wife or courtesan.” In the years since, scholars have begun to treat Mitchell’s 1970s lyrics as an artistic distillation of Baby Boomers’ struggles with premarital sex, motherhood, marriage, divorce, and career (Kutulas; Papayanis). Indeed, Sheila Weller’s popular biography Girls Like Us—soon to be further disseminated as a film—proceeds from the same contention. Both popular and academic feminists have placed Mitchell squarely on the field of an intraracial battle of the sexes. In the process, some have come perilously close to presenting contests between white women and men as exemplary of the history of the Sexual Revolution, unobscured by racial distinctions thought to lie beyond such a history’s purview. I hope it is not too late to suggest that the sonic documents Mitchell has left have never been divorced from projects of race-making, even when they circulated among fairly insulated white folk and rock consumers. That is, I hope re-visiting her maneuvers through gender, genre, and race offers a chance for further analysis of the process by which listeners acquire a sort of social synesthesia: an uncanny ability to conjure a racially and sexually specific body—and moralistic reactions to it—from disembodied recorded sound. Finally, I hope Mitchell’s story serves as a reminder that, even within racially homogenous settings, racial identification is actually part of the conduct of gender regulation and contestation.

Acknowledgements

For help in shepherding this article, I thank the anonymous reviewers, Andrew Ross, Phil Harper, Suzanne Cusick, Chinua Thelwell, Elliott Powell, and especially David Rentz and Arthur Knight. I am also grateful to the Women’s Studies Program at Duke University and those who commented on this work at public presentations.

Works Cited

- Beker, Marilyn. “Gentle Joni of the Mythical Mood in Folk-Rock.”Toronto Globe and Mail Apr. 1968. Web. 24 Apr. 2012.

- Broeck, Sabine. “Property: White Gender and Slavery.” Gender Forum14 (2006): Web. 25 Mar. 2012.

- Cady, Diane. “The Gender of Money.” Genders 44 2006. Web.

- Coates, Norma J. “Teenyboppers, Groupies, and Other Grotesques: Girls and Women and Rock Culture in the 1960s and Early 1970s.”Journal of Popular Music Studies 15.1 (2003): 65–94. Print.

- den Tandt, Christophe. “Men at Work: Musical Craftsmanship, Gender, and Cultural Capital in Classic Rock.” Reading Without Maps?: Cultural Landmarks in a Post-canonical Age: A Tribute to Gilbert Debusscher. Brussels: Peter Lang, 2005. 379–99. Print.

- Dyer, Richard. Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2003. Print.

- Echols, Alice. “‘Shaky Ground’: Popular Music in the Disco Years.”Shaky Ground: The ’60s and Its Aftershocks. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002. 161-92. Print.

- ———. “The Soul of a Martian: A Conversation with Joni Mitchell (1994).” Shaky Ground: The ’60s and Its Aftershocks. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002. 207–22. Print.

- Fellezs, Kevin. Birds of Fire: Jazz, Rock, Funk, and the Creation of Fusion. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011. Print.

- Halberstam, Judith. Female Masculinity. Durham: Duke University Press, 1998. Print.

- Henderson, Stuart. “‘All Pink and Clean and Full of Wonder?’ Gendering ‘Joni Mitchell,’ 1966-74.” Left History 10.2 (Fall 2005): 83–109. Print.

- Himes, Geoffrey. “Music and Lyrics.” Jazz Times December 2007. Web. 22 Jun. 2011.

- Holden, Stephen. “POP VIEW: Three Women and Their Journeys in Song; Too Feminine for Rock? Or Is Rock Too Macho?” New York Times 14 Jan. 1996. Web. 3 May 2011.

- “Into the Pain of the Heart.” Time 4 Apr. 1969. Web. 5 May 2011.

- “Joni Mitchell Made a Companion of the Order.” Toronto Globe and Mail 31 Oct. 2004. Web. 12 July 2011.

- Keightley, Keir. “Reconsidering Rock.” The Cambridge Companion to Pop and Rock. Ed. Simon Frith, Will Straw, and John Street. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. 109–142. Print.

- Kennealy-Morrison, Patricia. “Rock Around the Cock (1970).” Rock She Wrote: Women Write About Rock, Pop, and Rap. Ed. Evelyn McDonnell & Ann Powers. New York: Cooper Square Press, 1999. 357–63. Print.

- Kutulas, Judy. “‘That’s the Way I’ve Always Heard It Should Be’: Baby Boomers, 1970s Singer-Songwriters, and Romantic Relationships.” The Journal of American History 97.3 (2010): 682–702. Print.

- Mitchell, Joni. Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter. Asylum, 1977. Vinyl Recording. Album Packaging.

- ———. Hejira. Elektra / Wea, 1976. Vinyl Recording. Album Packaging.

- ———. Mingus. Elektra / Wea, 1979. Vinyl Recording. Liner Notes.

- Morrissey. “Melancholy Meets the Infinite Sadness.” Rolling Stone 6 Mar. 1997. Web. 2 May 2012.

- Morse, Steve. “Tiger, Tiger.” Boston Globe 1 Oct. 1998. Web. 30 Apr. 2011.

- Nelson, Paul. “Folk-Rock.” The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll. Ed. Jim Miller. New York: Random House, 1976. 216–221. Print.

- Nelson, Sean. Joni Mitchell’s Court and Spark. New York: Continuum, 2006. Print.

- Papayanis, Marilyn Adler. “Feeling Free and Female Sexuality: The Aesthetics of Joni Mitchell.” Popular Music and Society 33.5 (2010): 641–655. Web. 18 Aug. 2011.

- Popple, Ian. “Honouring Joni.” McGill Reporter 28 Oct. 2004. Web. 7 May 2012.

- Porter, Ross. “Joni’s Jazz” CBC Archives. 11 Feb. 2000. Web video. 2 May 2011.

- Roediger, David R. The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class. Revised. New York: Verso, 1999. Print.

- Rose, Tricia. Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, 1994. Print.

- Ross, Marlon Bryan. Manning the Race: Reforming Black Men in the Jim Crow Era. New York: New York University Press, 2004. Print.

- Sanneh, Kelefa. “The Rap Against Rockism.” The New York Times 31 Oct. 2004. Web. 16 Apr. 2011.

- Spillers, Hortense J. Black, White, and in Color: Essays on American Literature and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003. Print.

- Strauss, Neil. “The Hissing of a Living Legend.” The New York Times4 Oct. 1998. Web. 1 May 2011.

- Tate, Greg. “Black and Blond.” Vibe Dec. 1998. Web. 2 May 2011.

- ———. “The Long Run.” Vibe Feb. 1997. Web. 2 May 2011.

- Tosoni, Joan. Joni Mitchell - Painting with Words and Music. Eagle Rock Entertainment, 2004. DVD.

- Wald, Elijah. How the Beatles Destroyed Rock n Roll: An Alternative History of American Popular Music. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. Print.

- Watts, Michael. “The Divine Miss M.” Melody Maker 27 Apr. 1974. Web. 7 May 2012.

- Weller, Sheila. Girls Like Us : Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon and the Journey of a Generation. London: Ebury Press, 2008. Print.

- Whitesell, Lloyd. The Music of Joni Mitchell. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. Print.

- Wiegman, Robyn. Object Lessons. Durham: Duke University Press, 2012. Print.

- Wild, David. “A Conversation with Joni Mitchell.” Rolling Stone 30 May 1991. Web. 30 Apr. 2011.

- Willis, Ellen. “Records: Rock, Etc.” (1968) Rock She Wrote: Women Write About Rock, Pop, and Rap. Ed. Evelyn McDonnell & Ann Powers. New York: Cooper Square Press, 1999. 419-23. Print.

- Wolk, Douglas. “Thinking About Rockism.” Seattle Weekly. Seattle, May 4, 2005. Web. 18 Apr. 2011.

- Yaffe, David. “Working Three Shifts, and Outrage Overtime.” The New York Times 4 Feb. 2007. Web. 5 May 2011.