The Gender Politics of Justice: A Semiotic Analysis of The Verdict

[1] The Verdict (1982), directed by Sidney Lumet, is not the kind of film that has received attention from feminists. Unlike Alfred Hitchcock’s films (a repeated source of inspiration for psychoanalytic feminist film theory), Lumet’s films are usually perceived as liberal rather than conservative in their politics, as strongly grounded in a vision of social justice and dedicated to the exposure of corruption in the modern life of institutions and law enforcement. At first glance, there seems to be little for a feminist to critique in Lumet’s films. In The Verdict as in many of his other films, Lumet overtly criticizes the abusive privilege of white male patriarchy. The plot of this particular film follows the course of a medical malpractice lawsuit. It is brought on behalf of a comatose woman whose life was destroyed when she was improperly given a general anesthetic during childbirth in a church-owned hospital. The bishop of the church retains a wealthy defense attorney who does not hesitate to intimidate the working-class plaintiff, spy on the plaintiff’s lawyer, and bribe witnesses. The plaintiff’s alcoholic attorney, Frank Galvin (Paul Newman), is no better. He drinks instead of working on the case and he lies to his client. The judge is described as “a bagman for the boys downtown.” The Verdict is characteristic of Lumet’s films in its dense and textured portrayal of corruption in American institutions–here, in the law offices of Boston, the judges in its court system, the doctors in hospitals, and the bishops in the church. The film exposes how law and professional ethics are abused at every turn to support and reinforce the power of a white male propertied class — whether they are bishops, judges, lawyers, or doctors.

[2] From the perspective of feminism, what is also striking aboutThe Verdict is the location of compelling, credible testimony in a woman witness. Arrayed against the male-dominated forces of corruption, she brings their power and influence to a standstill in the courtroom climax that concludes the film. Her testimony is the definitive moment in the film, determining the outcome of the trial at the heart of the film’s narrative. As the authoritative location of authenticity and truth, she enables the court to render a just verdict in a society otherwise portrayed as hopelessly corrupt and ridden with deceit. As the credible point of orientation for both the characters within the narrative and the viewers watching it, the character of the woman witness runs counter to the psychoanalytic theory that the “female masquerade” is inevitable, or that women can only be the object within a patriarchal system (Doane, Mulvey, Silverman, Rose). Far from representing lack, the woman witness supplies what is palpably lacking in the patriarchal narrative. Her testimony grounds the meaning of the evidence, the meaning of the trial, the meaning of words and symbols, and the meaning of the film. This woman-as-object, with all eyes gazing on her as she takes the witness stand, transforms her silent object-status into an authoritative subjectivity as her testimony supplants the authority of the judge and the legal system, compelling acceptance from all characters and the approbation of the empanelled spectators, the jury. And lastly, she achieves all this without an act of violence, without recourse to the methods of the heroine of contemporaneous slasher films.

[3] So, what’s to critique? The woman witness in The Verdictseems to be the kind of woman character that feminist critique has implicitly called for as an alternative to Hollywood’s negative stereotypes of women. And yet, in viewing this film, there can be no question that the deployment of gender that underlies the system of justice in this film exacts a severe social price in constructing the credibility of the woman witness, a social price unacknowledged and unrecognized by the film’s drama. As I will show, in the course of the character’s development, what makes her a credible witness also excludes her from the equality that the justice system appears to promise. She is herself denied the protection of the law whose truth she upholds in the face of corruption.

[4] To understand how the prejudicial construction of female gender functions in a liberal film like The Verdict, we need to begin in a different place from the premises of feminist psychoanalytic theory, and start instead with the demiurge of difference himself, the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure. This is an especially suitable approach to this film because The Verdict, more than most films, is carried by the dialogue. The author of the screenplay is David Mamet, a dramatist. Mamet’s authorship gives this film a more dramatistic quality. There is little use of film geography and the cinematography is designed to highlight the stellar performances of the actors. The words of the dialogue rather than the cinematography create and develop the drama of the film, putting the emphasis on language and individual performance. Moreover, much of the story is about the misuse of language by professional class men whose power consists in their ability to control social institutions through their use of words (rather than through violence). Of all the institutions condemned by the film, the legal system is represented as the most corrupt and the most purely dependent on language. The chief lawyer for the defendants is described as the “prince of darkness” in his verbal manipulations. One of the plaintiff’s lawyers despairingly observes — regarding the comatose victim — “He’ll have people who say they saw her on the beach at Marblehead last week.” In keeping with Saussure’s theory of the arbitrariness of signs, the legal system is portrayed as arbitrary, without the logic of ethics or justice, a legal system that thrives on the belief that, since there are no essences, there can be no justice. In short, the law is a system of arbitrary rules. In an ironic inversion of the typical psychoanalytic concept that the arbitrary signs of language “have the force of law” –that is, they function with stability–The Verdict goes out of its way to show how capricious and unstable the law really is. It is a vicious, even deadly, game dominated by power brokers who perceive the law as freely exploitable because it has no inherent meaning.

[5] The counterweight to this arbitrary signification is the woman witness who halts the infinite regression of signs and restores truth and integrity to the legal system. While it is easy to see that The Verdict is reflective of Saussure’s theory that there are no essences, only differences, it is vitally important to recognize that the woman witness is also derived from Saussurian linguistics, too. She is emblematic of a crucial exception that Saussure made to his theory of difference. In the locus classicus of structuralist semiotic theory, his Course in General Linguistics, Saussure makes a massive qualification to the universal applicability of his theory of difference. He exempts symbols because they are “natural” signs. The passage is one where Saussure pauses to explain why he is using the term “sign” and not “symbol” regarding the basic unit of his linguistic theory:

The word symbol has been used [by others] to designate the linguistic sign, or more specifically, what is here called the signifier. Principle I [“The linguistic sign is arbitrary”] in particular weighs against the use of this term. One characteristic of the symbol is that it is never wholly arbitrary; it is not empty for there is the rudiment of a natural bond between the signifier and the signified. The symbol of justice, a pair of scales, could not be replaced by just any other symbol, such as a chariot (68).

[6] The example of the scales of justice also has far-reaching implications for women, although this is not apparent from Saussure’s own text. Saussure was inaccurate in his description of the symbol of justice. Put simply, Saussure believed the symbolic scales of justice were not an arbitrary sign. Unlike linguistic signs, the visual symbol of the scales “is not empty” (not a structuring lack) and is instead based on a “natural bond between signifier and signified.” It was thus excluded from the implications of his semiotic theory of difference. Saussure limited his theory of difference exclusively to language, to linguistic signifiers. Revolutionary though this was, he left intact the centuries old tradition of reading the book of nature as a system of signs, and explicitly rejected the idea that these natural signs were arbitrary. Saussure argued for the instability of the linguistic signifier only under the condition of maintaining a stable signfication elsewhere–in the world of natural signs. That such “natural bonds” were outside the purview of linguistics has important implications for the concept of justice. What the scales of justice historically had symbolized was the capacity to perceive the truth. If that capacity simultaneously lies outside language, then the use of language in the service of justice can be nothing more than a ruse — precisely what it is in the legal system portrayed inThe Verdict.

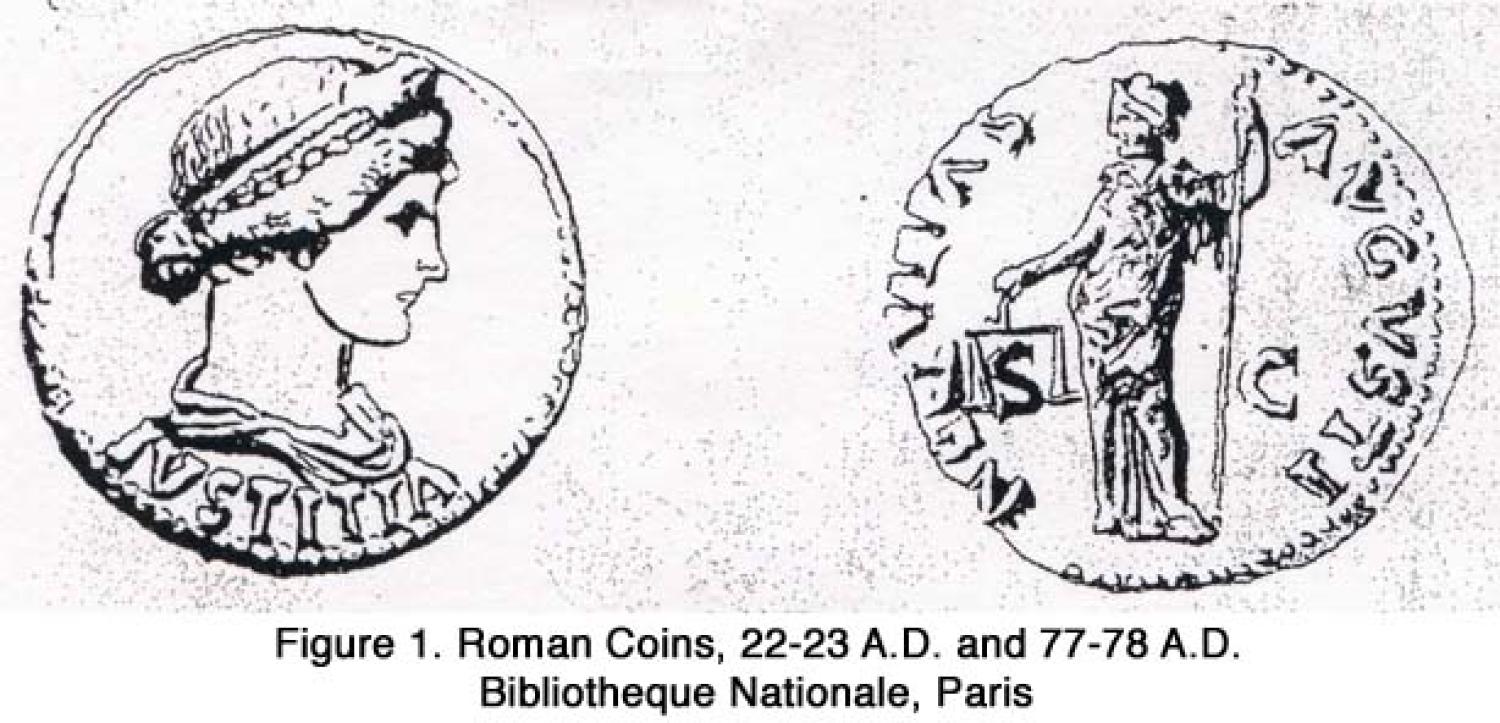

Historically the pair of scales symbolized justice only when it was held by a woman. Martin Jay has traced the history of this image. In the earliest form of this image, the woman holding the scales was the Roman goddess Justitia. It is Justitia holding the scales, not just the scales alone, that has served for nearly two thousand years as the symbol of justice in Western culture. Without her, the scales would be indistinguishable from a grocer’s or trader’s scales. Her image can be found as early as the first century A.D. on Roman coins (figure 1), and is still prevalent in our own time. While there were alterations–the staff becomes a sword,a blindfold is added in the Renaissance–the figure remains consistently female. A secular image, she has adorned everything from civic buildings to the covers of popular novels (figure 2). The “natural bond” symbolized by the scales is also a “natural bond” between female gender and justice, a bond that serves as the foundation of credibility for the woman witness in The Verdict. Saussure’s own effacement of Justitia from his text is duplicated in the narrative of The Verdict by the defendants, who never mention to their attorneys that there is a woman witness. As with Saussure, it is as if she did not exist. The Verdict is the drama of Justitia’s restoration, how she is missed, what it takes to restore her and give her credibility. What could highlight her effacement more dramatically than a courtroom showdown between an angry Justitia and a white male professional class defendant (the hospital’s anesthesiologist) – a man who just happens to be, like Saussure, the eminent author of the most respected text in his field? This is the climax of The Verdict.

[7] It is practically a reflex action for a feminist to point out that a ‘natural symbol’ is culture masquerading as nature, that the woman holding the scales of justice is no less arbitrary than any other cultural sign. However, it is all too easy to reach the psychoanalytic conclusion that the alternative is to see Justitia as an empty signifier, that it is Justitia as a structuring lack that centers and limits the play of signifiers that is the legal system. Deconstruction requires a different move. As Derrida summarized in his most well-known essay, “Structure, Sign, and Play,” the freeplay that typifies deconstruction “is always an interplay of absence and presence, but if it is to be radically conceived, freeplay must be conceived of before the alternative of presence and absence” (264, emphasis added). Simply to convert presence into absence is not a deconstructive critique but rather the avoidance of one. In discussing the main ideas of his essay Derrida said: “First of all I didn’t say that there was no center, that we could get along without the center. I believe that the center is a function, not a being–a reality, but a function” (271). So, how to consider Justitia as a function is the task of a deconstructive critique. To this end, it is important to recognize that Justitia’s exclusion from language is not based on a concept of lack. She does not function in this way. It is because she has a direct relationship to the real that she is exempted from the system of the arbitrary, empty signifiers of Saussurian signs. Her authority is based instead on the “natural bond” of signifier and signified that characterizes non-arbitrary symbols. This exclusionary female subject is also a non-Lacanian subjectivity in the sense that it is conditional upon exclusion from –not inclusion in– the linguistic system. That exclusion is underscored by the visual quality of the natural sign. It is an image, not language. Justitia functions as a direct relation to the real, as an exclusionary subject, and as an image defined as a non-linguistic sign.

[8] The practice of deconstruction was developed mainly with texts, not images. However, in Signs and Meaning in the Cinema, Peter Wollen has cogently argued that images convey meaning apart from and differently from linguistic structures (119-21). The structuralist privileging of language as the paradigmatic semiotic system has obscured how images function in ways qualitatively different from language. To deconstruct an image, then, requires a different kind of semiotic vocabulary. Wollen argues for the value of Charles Sanders Peirce’s semiotics as a way of articulating how natural signs function (120-24). Saussure’s natural sign is an instance of Peirce’s indexical meaning.

[9] For Peirce, the index is an aspect of signification that asserts an existential bond between a sign and what it signifies (CP2.283-308, 4.447-8). It was, as Peirce said, “a relation of fact.” An indexical sign functions as an invariable signal in relation to other signs. It is a signal whose variability is determined, not by its relation to other signs, but by its inherent relation to what it signifies. This is what makes the index different from a metaphor, which may assert a resemblance, but not one that is based on an existential bond between the metaphor and what it depicts. Peirce distinguished between the iconic sign, which has only a relation of “external likeness” to its object, and the indexical sign, which has an intrinsic relation of fact to its object. An image such as a painting or a diagram is an example of an external likeness, as is metaphor. The natural image, by contrast, claims an intrinsic relation to its object, a natural bond between the signifier and the signified. A weathervane, for instance, is an index that images the direction of the wind. The direction in which the weathervane points is materially, intrinsically related to the wind itself. A thermometer is an index of temperature. A barometric gauge is an index of barometric pressure. Smoke is an index of fire. The index is also a way of describing the Derridian observation that a center is both inside and outside the structure it centers. An index has a foot in both camps. It is at once part of the signifying system and not subject to it. It is at once a sign and inherently connected to its object. An index is not the fusion of sign and object–there is always a tension between the indexical sign and the object it represents. One sees the smoke without necessarily seeing the fire. One can see the mercury in a thermometer, but one does not literally see the temperature it indicates. Similarly, we don’t see barometric pressure itself, only the gauge’s visual indication of it.

[10] The concept of indexical meaning seems quite compelling when examples are taken from natural science. But Peirce’s idea of physical science extended to other realms and in more questionable ways, as in this example: “I see a man with a rolling gait. This is a probable indication that he is a sailor” (2.285), an example repeated without critical comment by Wollen (122). Taken in this direction, indexical meaning can become the pseudo-scientific basis for racist prejudice, as Peirce himself demonstrated in his own use of racial profiling (Kibbey, Peirce and Griffith). Peirce interpreted physical characteristics as indexes of character, African-Americans as morally inferior, and like many others, he believed this was a matter of scientific fact. It is the same idea that underlies Saussure’s concept of a natural bond between signifier and signified. The so-called natural bond between female gender and justice is an instance of what we might call the pseudo-science of gender profiling.

[11] Wollen emphasizes yet another problematic example of the index from Peirce, the photographic image. Peirce explained:

Photographs, especially instantaneous photographs, are very instructive, because we know that in certain respects they are exactly like the objects they represent. But this resemblance is due to the photographs having been produced under such circumstances that they were physically forced to correspond point by point to nature. In that aspect then, they belong to the second class of signs [indexes], those by physical connection (CP2.281).

[12] Mamet’s script explores the idea of indexical meaning with unusual rigor. It is the idiom of the script, both its subject and its method. Mamet develops and positions his characters in The Verdict to exemplify various dimensions of indexical semiotics. The story opens with the lawyer Frank Galvin drinking at a bar. The example of the sailor with the rolling gait becomes in The Verdictthe plaintiff’s lawyer with the rolling and stumbling gait of an alcoholic. Galvin’s indexical gestures of drunkenness dominate the visual portrayal of his character in the early part of the film as he staggers from scene to scene, lurching, bleary-eyed, bumping into things, and speaking with a slur. Galvin acts like a man possessed, controlled by indexical gestures that are unnatural and inimical to his body. These indexical gestures of drunkenness diminish gradually, in direct relation to his success in arguing the case to a victorious conclusion. In the last scene, he sits calmly at his desk with a cup of coffee, miraculously cured of severe alcoholism. The over-all implication is that indexicality cannot characterize the white male body except in its moments of degradation. Galvin’s backstory implies as well that justice, also indexical, is properly outside the male body. Galvin had originally had a very promising career, starting out at a large and prestigious law firm, and marrying a senior partner’s daughter. When he discovered that his firm had bribed a juror in a case he was trying, “to help him out,” he denounced the jury tampering and attempted to report his own law firm to the judge. On his way, he was himself arrested for jury tampering and jailed–an action obviously arranged by his law firm. About to be disbarred, he apologized to his law firm. Charges were dropped, but his new wife divorced him, and he lost his job and his reputation. This chain of events led him to drinking heavily. The gestures of drunkenness are an iconic disturbance caused by the attempt of a man to play a female role. InThe Verdict, men may admire justice, but they cannot themselves hold the scales of justice. They disgrace and pervert their own masculinity if they try to be the arbiter of justice because justice is indexically linked to the female gender.Peirce distinguished between the chemical process of materially making a photograph, which is the source of its indexicality, and the iconic representation of someone or something in the photograph. An iconic sign by itself has no necessary factual relation to its object, no intrinsic “physical connection” as the index has. However, Peirce believed that the scientific indexicality of the photographic process provided “assurance” of the truth of the iconic image in the resulting photograph, testifying, so to speak, to the truth of the image in the photograph (CP 4.447). Wollen points out the importance of this idea in film studies as the basis for André Bazin’s well-known theory of cinematic realism (9-16, 23-8). It is also crucial to The Verdict, where the resolution of the plot hinges on the realism of photography, the indexical validity of photographic evidence, the image outside language that can claim a ‘relation of fact.’

[13] Far more complex is the matrix of semiotic ideas involving the variety of women characters in the film. As Mamet develops the ideology of female gender and justice that structures the narrative, he restores the effaced Justitia, not as Everywoman but as one particular woman. Not every woman can stand in the place of Justitia because the so-called natural bond between women and justice can be suppressed or compromised when a woman participates in language. That is, Mamet observes Saussure’s sense of opposition between the semiotics of language and natural images. For Justitia to serve as a natural image, the “natural bond” must be preserved. Otherwise she will, like arbitrary signifiers, be “empty.” Since the role of Justitia is set off not only from white professional class men, the pre-eminent language users, but also from other women in the film, it is instructive to see what women are not cast in the role of Justitia.

[14] Not Deborah, the victim of medical malpractice on whose behalf the lawsuit is brought. While the events of her life are the subject of the trial, none of these events is portrayed in the film. We find out about her only through the language of other characters. Her backstory is this: Deborah, a wife and mother who was pregnant with her third child, went to the hospital to give birth. While in the delivery room under a general anesthetic, she “threw up in her mask” and choked on her vomit. Her heart stopped and it took several minutes to restore breathing. By that time, the baby was dead and Deborah had suffered severe and permanent brain damage. Her husband abandoned her, taking their two other children with him. She is left in the care of the hospital, with only her sister to be concerned about what has happened to her and what will become of her. It is her sister who retains the lawyer Frank Galvin to sue for malpractice.

[15] In the backstory of what happened in the operating room, Mamet literally tables the Victorian verities of motherhood, discounting the “separate sphere” of motherhood as a viable outside position for Justitia. Deborah lies comatose throughout the narrative, kept alive only by modern technologies. As if to underscore his point, Mamet includes the detail that she was already anemic before she entered the delivery room. Within the film, we only see her in an unconscious, inert state. We have one persistent image of Deborah: She is in an old hospital, lying on her side in a patient’s gown, partly covered by a sheet, her face largely hidden behind a respirator mask. This victim is the sad occasion for the malpractice suit being brought, but she is not Justitia. She is referred to both as dead and not dead, physically surviving only in the most minimal sense. She has no authority, no consciousness, no voice, no judgment and no movement. She is as empty as the Saussurian arbitrary signifier.

[16] Early in the film, when the lawyer goes to see Deborah in the hospital, he carefully takes pictures of her–Polaroid snapshots that we see developing as he holds them. His client, Deborah’s sister, has also brought him snapshots of Deborah, to show what she was like before the operation. The snapshots, both his and hers, have no narrative consequences in the story. The lawyer takes the snapshots to a settlement conference, but doesn’t even show them to the other side, sensing the futility of doing so.

[17] The lawyer’s and the sister’s snapshots associate Deborah with an example of indexical meaning, the realist photograph. For Bazin (and for Barthes as well), the indexical quality of photography was the basis for the cinematic realism he praised so highly. He believed a photograph can create a true image because, unlike painting, it is an image made by a mechanical process, without human intervention (9-16). Bazin’s metaphor for photographic realism–the molding of a death mask (Wollen, 125) — is evocative of the image of Deborah in The Verdict. However, where Bazin used the metaphor to emphasize the accuracy of the image, Mamet gives it a very different connotation. Deborah choked almost to death behind an anesthetic mask, and now lies perpetually hooked up to a respirator mask, her face hidden behind it. In Mamet’s literalization of this metaphor, Deborah the mother has nearly choked to death behind the mask of Realism, lying in a hospital built in Bazin’s time. The snapshots that characterize Deborah are not equal to the present day challenge of medical malpractice. The realism of the snapshot, though indexical in itself, is useless in a court of law because it does not reveal what the guilty act was, only its result. As evidence, it relies on association rather than indexicality. Consequently, it leaves open the possibility, as the defense points up, that there was no guilty act. It also functions associatively in the film’s plot. It associates crucial elements–the image of a woman, the signifying possibilities of photography, and a sense of wrongdoing. These materials, reconfigured and transformed, will become the crucial testimony offered by Justitia.

[18] Also emphatically not holding the scales of justice is the woman lawyer (Charlotte Rampling) who works for the law firm defending the Catholic hospital. As a woman lawyer, positioned within the linguistic system of legal institutions, she might seem to be ideally placed for the role of Justitia. Instead, she is the opposite. The woman lawyer exemplifies how female gender is corrupted by entering into the linguistic system of the law. She initiates a sexual relationship with the plaintiff’s lawyer to obtain confidential information about the case. Her degradation and dishonesty are not her only qualities. She is also ineffective. She fails to obtain the crucial knowledge that is needed, and also fails to conceal from Galvin her real motive for the relationship. An ineffective member of the defense team, and inept at the slippage of signifiers, she becomes an alcoholic at the end of the film. As Galvin was an alcoholic at the beginning of the film, the outcome of his attempt to play a female role, so here the woman attorney becomes an alcoholic as the outcome of her attempt to play a male role, the role of lawyer. In the last frames of the film, the woman lawyer is pictured lying in bed, alone and drunk, with a towel over her aching eyes and forehead. The towel is a satiric reminder of the blindfolded Justitia, here in a profane and inverted iconology that bespeaks the ethical blindness of the woman lawyer.

[19] The Verdict is heavy-handed in its hostility toward women in the legal profession, a hostility that is reprised in a recent liberal film, The Insider (1999). The woman lawyer in this film, who is an in-house corporate lawyer for CBS Corporation, opposes broadcasting the insider’s testimony on CBS’s “60 Minutes.” Far more successful and prosperous in her career than her predecessor in The Verdict, and far less confused about her own motives, the woman lawyer in The Insider oozes evil. She attempts–but ultimately fails–to suppress crucial testimony against the tobacco companies because she will personally profit from the sale of CBS Corporation. She doesn’t want to jeopardize the sale by risking a lawsuit from the tobacco industry. Her over-riding private interests are hostile to justice, so hostile that the woman lawyer is the logical opposite of Justitia. Justitia is by definition outside the linguistic system. The woman lawyer deeply within it is the epitome of corruption, the ultimate symbol of a legal system that freely abandons justice to protect property interests.

[20] Deborah’s working-class sister may seem to have a greater claim to the role of Justitia. She and her husband are the ones who initiate the civil suit against the anesthesiologist and the hospital for malpractice. Not unattractive but not seductive either, the sister easily claims the sympathies of the viewer. As she explains to the lawyer, she needs to sue for damages so she can afford to put her sister in a nursing home. The sister feels guilty about what she is doing. She wants to leave Deborah, not stay with her. (The sister plans to leave Boston with her husband and go to Arizona, where he has gotten a new job.) The ideology of the natural bond of female gender and justice appears intermittently in the conflicts the sister experiences. She feels guilty about seeking money for what has happened. Although she feels an injustice has been done toward Deborah, it is an injustice that she herself is now exploiting for financial gain to rid herself of the burden of her comatose sister. The natural bond of female gender and justice indirectly asserts itself in the guilt-ridden and tearful apologies of the sister for acting in a self-interested way, for using the system of justice to obtain money.

[21] While not excluded from language, the sister is clearly not comfortable within it. She speaks hesitantly, and she relies on snapshots of her sister before the operation to convey the magnitude of what has happened, fearful that her own words will be inept and unpersuasive. She does not testify at the trial. A silent, submissive participant in the linguistic system of the law, her sense of justice is compromised by her self-interest. Initiating the lawsuit on behalf of her sister, she is an interested party, that is, a participant in the linguistic system of signifying difference even when she is literally silent. She cannot hold the indexical scales of justice. She can only cry indexical tears into her handkerchief.

[22] This should not surprise us, however, because “sister” is the word Saussure uses in his initial illustration of the arbitrariness of linguistic signs. “Sister” illustrates the meaning of Principle I, the arbitrary nature of the linguistic sign (67). The bonds of familial relationships are emphatically not what is meant by the “natural bond” of signifier and signified that informs the natural images of Saussure’s theory. The deployment of the sister in the film bears this out. The sister enters into the legal system of a civil suit to terminate her relationship with her sister, and she succeeds. The sister is never imagistically portrayed in any scene with Deborah. Their sisterly relationship exists only in language, in the words of the dialogue. It has no visual representation in the film.

[23] The entrance of the woman character who fulfills the role of Justitia, Kaitlin Costello (Lindsay Crouse), comes very late in the film. As the case starts slipping away from Galvin, his thoughts turn to outside-ness, to what happened outside the operating room rather than what happened inside it. Rereading the documents on the case, he suddenly realizes he has overlooked something. The nurse who filled in the admitting form, but was outside the operating room at the hospital, may have crucial knowledge. Thus begins the search for the admitting nurse, Kaitlin Costello, the outsider who proves to be the Justitia of the film.

[24] The closer we get to the discovery of the Justitia character and her entrance into the story, the more we become enmeshed in various forms of non-linguistic meaning and varieties of outside-ness, a discourse befitting the indexical scales of justice. Not surprisingly Galvin is unable to find her through language. Discovering her name, he attempts to locate her by phone, calling innumerable possibilities in various city directories. Unable to find her or anyone who knows her through his many phone conversations, he resorts to stealing the telephone records of the one nurse at the hospital who, he guesses, is still in contact with Kaitlin. He dials the number and the woman he seeks answers the phone. It turns out that she has since married and changed her last name. In summary the attorney finds her, not through language, but through numbers. Language is not a reliable indicator of Justitia’s location.

[25] Much of Kaitlin’s credibility is constructed impressionistically in the drama by her absence from the various scenes of corruption. She has no connection to the victim or her sister, and no connection to the lawyers. She no longer works at the hospital and no longer lives in Boston. She has had no part in the drama of the film up to this point. Indeed, the viewer has not even known of her existence. Although she has married, the story discloses nothing of her husband, and she apparently has no children. Her only social relation is a very brief scene when the attorney finally locates her at the day care center in New York where she now works. He observes that she is “great with kids” and we see her taking care of other people’s children as Galvin approaches her. She is friendly toward him until she sees the subpoena in his coat pocket. She frowns and draws back, affirming her outsideness again by demonstrating her reluctance to testify. Even at this point she does not enter into the narrative. This remains an isolated scene and we know nothing more of her until she walks into the courtroom to testify (just ten minutes before the conclusion of the film). When she enters the courtroom, no one acknowledges her in any way. Her testimony is bracketed by long shots of her walking in and walking out, shots that symbolize her social distance from the people and events involved in the lawsuit. She has no interaction with anyone other than the lawyers who ask her questions, and when she walks out immediately after the testimony, she disappears from the film.

[26] Kaitlin’s testimony is the crucial moment, not only in the story of the film, but also in its semiotic development. The subject of her testimony has been predetermined by the wealth of information we already have about the case even before she walks into the courtroom. We already know basically what happened to Deborah. The only thing we don’t know for sure is when Deborah last ate. We have found out this is crucial because a general anesthetic should never be given to a patient who has recently eaten. Her sister claims Deborah ate 1 hour before going to the hospital. The hospital admitting form says 9 hours. How can these two different numbers be reconciled? Kaitlin’s role is to explain the discrepancy. Kaitlin says Deborah told her 1 hour and she wrote a 1 on the admitting form. As she speaks, she is backlit to give her an aura of natural light from the window above and behind her — an indexical sign of her credibility. She explains further that, after the disaster in the delivery room, the anesthesiologist confessed to her that he hadn’t looked at the form and he told her to change the 1 to a 9, hence the slippage of signifiers. As to who actually altered the number, we never find out. But Kaitlin makes clear that it was not herself: “I didn’t write a nine. I wrote a one.” At the heart of her testimony, the crux of what she says is in numbers rather than words.

[27] It is important to recognize that, when the Justitia character testifies, she does not testify about what was done to Deborah. That the number on the admitting form was changed after the operation was not the cause of Deborah’s injury. Kaitlin testifies solely about the written record of the time line. What makes it truth of the most fundamental kind is the manner in which it reflects Saussurian semiotics. The doctor’s legal wrongdoing, the reason for his conviction, is his disregard of the second principle of language in Saussure’s theory:

Principle II: The Linear Nature of the Signifier.

The signifier, being auditory, is unfolded solely in time from which it gets the following characteristics: (a) it represents a span, and (b) the span is measurable in a single dimension; it is a line.While Principle II is obvious, apparently linguists have always neglected to state it, doubtless because they found it too simple; nevertheless, it is fundamental, and its consequences are incalculable. Its importance equals that of Principle I [“The linguistic sign is arbitrary”]; the whole mechanism of language depends upon it (70, emphasis added).

[28] The difference in emphasis becomes more evident when the defense attorney (James Mason) begins his cross-examination. It appears at first that he will successfully challenge Kaitlin’s credibility as he implicitly accuses her of perjury and of failing to fill out the admitting form correctly. Moreover, Kaitlin has no proof of what the doctor said to her. It is simply his word against hers as to whether he looked at the form before commencing the operation. The focus of judicial scrutiny shifts to the falsification of linear time, and from language to image, when Kaitlin pulls out a photocopy she made. It’s a photocopy of the original admitting form as she had filled it out, with a one. The photocopy proves to be the damning evidence, not Kaitlin’s verbal testimony. The photocopy is a mute testament to the truth and it, rather than Kaitlin’s words, carries the day.Although modern poststructuralism has drawn heavily on Saussure’s first principle, the arbitrariness of linguistic signs, his second principle of linearity–to him an equally vital foundation for his theory–has been generally disregarded. Mamet restores its importance, and assigns it the magnitude Saussure gave it, by making the testimony about the time line the turning point in the trial. Although Deborah’s comatose condition is the occasion for the lawsuit, the Justitia character actually testifies only to the doctor’s violation of linear time, first in his neglect of it, and second in his desire to alter the record of linear time. The initial neglect of linear time occurs with his failure to read the admitting form before beginning the operation–the mistake that resulted in Deborah being put into a coma. However, it is his second act, the falsification of the record of linear time, changing the 1 to 9, that proves his guilt and causes his conviction. The scales of justice tip away from Deborah herself and toward the falsification of linear time as the more weighty issue.

[29] The photocopy is nothing like the kind of photographs that Bazin had in mind when he wrote of the photograph’s power of authenticity, but it fulfills his criteria of the true image far better than neo-realist cinematography does. The photocopy eliminates the intervening hand of the photographer far more thoroughly than the realist images at the foundation of Bazin’s theory of photography. Bazin’s theory now seems naïve in its belief that the photograph comes about without human intervention in the creation of the image, for we now recognize that the photograph is a work of art, a subjective composition in which content is inseparable from form. The invention of the photocopy, however, breathes new life into Bazin’s theory of the realist photograph’s authenticity, and renews the idea of a photograph as composed without human intervention.

[30] At the moment the center overtly behaves as a center, structuring the significance of the narrative, signification passes from language to image. It does so through the medium of the Justitia character because, as an index, she enjoys a unique ‘relation of fact’ between sign and object. There is no dialogue about whether the photocopy is a true copy, about whether or not it was a forgery, because the Justitia character is its source. Her power is the power to close off such speculation, to halt the play of signifiers and ground their meaning in the indexical assertion of a sign’s unique relation of fact. Herself an index, she is the guarantor that it is a true copy and not a forgery.

[31] When confronted with the imagistic evidence of the photocopy, the defense attorney is, for the first time in the film, at a loss for words. Because he has controlled the discourse of the court up to this point, his stunned silence is quite important. It affirms the credibility of Kaitlin as Justitia, her legitimacy as the center that structures the meaning of the discourse. Recovering himself, he tries to get back to language. He tries to challenge her authority, her presence as Justitia–but not by questioning her to cast doubt on the truth of the photocopy. That he doesn’t do this implies his consent to her power. He turns instead to the judge and the rules of evidence. He objects to the photocopy being put into evidence, on the grounds that the original (which says 9 hours) is always to be preferred to a copy (which says 1 hour). That is, he tries to re-open the play of signifiers by recasting presence as absence. When the defense argues that the photocopy must be excluded from evidence, their argument is based on the idea of the photocopy as merely iconic–in Peirce’s terms, having no necessary relation to reality. But the photocopy is much more than this. Iconicity, indexicality, and conventional aspects of signification are fused within it, eliminating the tension between these differing concepts of the image as sign. It is an ideal sign, fulfilling Peirce’s belief that the most powerful sign is one that involves all three aspects of signification–the iconic, the indexical, and the linguistic (CP4.4480). It does so because the photocopy is a pictorial image of writing. Its quality as a sign that articulates a relation of fact is dependent on its indexicality, which in turn lends its relation of fact to the iconic image within the photograph–the conceptual image that we see when we view a photograph. And in this case, the indexical relation of fact extends to the writing that is pictured in the photocopy. The idealism of the ideal sign, its ability to function as a transcendental signifier, is secured by its material absence from the film itself. It might be expected that at this moment the film would give us a close-up shot of this important document, but it does not. Were it put on screen, it would become enmeshed in the montage of the film, involved in a relation to other signifiers that would compromise the distinctive claim of the index–that its variability is solely determined by its relation to what it represents.

[32] The judge sustains the defense and refuses to admit the photocopy into evidence. Ironically, his legitimate ruling seems morally outrageous at this point in the drama, a touchstone of his corruption, because it implies that the Justitia character lacks credibility as a witness. It seems at first that the case will be lost. However, when the photocopy is not admitted into evidence, it is placed exactly where it needs to be to achieve credibility–outside the linguistic system of the corrupt court. Empowerment lies in exclusion, not inclusion. The nature of Galvin’s closing statement to the jury builds on this exclusion. He begins by pointing out that “so much of the time we’re just lost. We say, please God, tell us what is right. Tell us what is true.” He implies, of course, that this case offers something different, that here the jury does not have to guess because they can know what is true. Galvin tells the jury that justice is not in any text or lawyer or courtroom protocol, that “you are the law.” In effect, he tells the jury to place themselves outside the court proceedings and its rules of evidence. Justitia and her believable evidence are then joined by the jury, who accept Galvin’s invitation to take an exclusionary subject position. They find for the plaintiff and grant damages even larger than what was requested.

[33] Although the sister wins the case, the priorities of justice turn out to be far different from what we might expect. The violation of linear time, not social injustice, is the crucial issue. Justitia functions as the key witness to naturalize linear time, to make it a natural image, to give it the assurance of indexicality. And linear time is very much in need of her. The line that represents linear time, both in Saussure’s description and in linear narrative generally, is a diagram. Semiotically, a diagram is an icon, not an index (CP2.278). Since icons have no necessary, intrinsic relation to what they signify, the line of linear narrative does not necessarily have anything to do with reality. Its verity must be conferred and confirmed by Justitia. In a manner analogous to the semiotics of the photocopy, she lends the indexicality of her “natural image” to the linear icon of time, to assure us that linear time is natural and real, an inherent characteristic of the world we live in. The Verdict suggests that there is a close relationship between the sanctity of linear narrative and the attainment of justice. It would seem that one can prove injustice only by proving that a white man has violated the record of linear time. Even so, this proof is not a recognition of social injustice as such. Instead, it is more directly a recognition and punishment of a white man’s betrayal of the foundations of his own linguistic system.

[34] That social justice is not the primary issue becomes more evident when we consider the predicament of Kaitlin Costello herself–whose married name, interestingly, is “Price.” Certainly she does pay a price as the stand-in for the goddess Justitia. When all is said and done, this is a backlash film, the compliments to Justitia notwithstanding. Unlike male whistleblowers, whose suffering is the story of the film in Serpico(1973) and, more recently, The Insider, Kaitlin Costello’s life is not the story of The Verdict. Nothing is made of the threats against Kaitlin by the doctor. He threatens to fire her and make certain that she’ll never work again. Because of his demand to falsify the record, which she refuses to do, she quits her job, leaves the nursing profession, and leaves Boston for New York. There is a split identity here–between the indexical figure of Justitia who is outside language, and the all-too-human Kaitlin whose employment placed her within the linguistic system of the hospital. The character of Kaitlin is split between her testimony as the Justitia character, which is solely about the linear record, and her testimony on cross-examination, where her personal story spills out of her. We glimpse the injustice against her only in this latter testimony, as she recalls her former life as a hospital employee and the destruction of her nursing career, but this is not dramatically sustained. Her verbal re-entry into this former life through her testimony is simultaneously the end of her authority. Speechless and sobbing, she leaves the courtroom and does not return, even for the verdict. No redress is offered to her. There is not even an expression of sympathy. Kaitlin the ordinary human being is excluded from the system of the law. Kaitlin as indexical sign, as the Justitia character, outweighs the significance of Kaitlin the person who suffered injustice. Like the semiotic paradigm of the photograph, the indexicality of Justitia is the determining aspect of signification of the character of Kaitlin, the determiner of fact as to who she is. It defines her as outside the law’s protection because she is outside its system, an exclusionary subject. Arbiter of justice, she cannot herself benefit from it.

[35] In effect, Justitia is allowed into court in The Verdict only to uphold both the proper record of linear time and to demonstrate that she asks nothing of the court as a human being. The human being’s story is instead the story of Galvin, the plaintiff’s lawyer. In a rigorously linear film, we follow his consciousness from the first to the last frame. We meet and know the women in the film only through his contacts with them. When Kaitlin supplies him with the power of the scales of justice, he wins the case and regains the respect of other lawyers. He sees himself as having conquered the corruption of the legal system. In actuality, he has only been restored to his place within it. Justitia’s testimony does not change the legal system. It sustains the legal system as it is, corruption and all. The defense lawyers lose the case, but nothing else happens to them. Nothing happens to the judge. The function of Justitia’s presence is to sanction the legal system as it is, notwithstanding all that we have learned about its corruption.

[36] The Verdict crystalized the cultural myth of the woman who holds the scales of justice, and its influence is evident in most of the Hollywood films about women and the law that have been made sinceThe Verdict. Although many more women have become practicing attorneys in the intervening years, the characterizations of women in The Verdict have remained more or less intact–the victim who is physically attacked in some way, the sister/peer who has some connection to the legal system and vaguely aims at justice, the woman attorney who is a failure, and the independent figure of Justitia who gives order and meaning to the story. Succeeding films have sometimes borrowed only part of the story, like Jagged Edge(1985), in which the woman attorney is a pathetic figure, easily duped by men in court and in her sex life, flagrantly inept in her judgment. The story turns into a slasher film as the woman attorney pulls out a gun to solve her otherwise unresolvable dilemma–the client-lover-murderer who tries to kill her. Other films have combined roles, as The Accused (1988), where a waitress, a rape victim, also plays Justitia. Denied any opportunity to speak on her own behalf in the case, she must rely on the prosecuting woman attorney who ignores her and settles the case as an issue of reckless endangerment. When the victim/Justitia character becomes angry with her, the woman attorney repents her “mistake” and goes back to court, but not to much purpose. She is stronger than the sister/peer character, another waitress, but the victim’s own testimony centers the story. The woman attorney is eclipsed when the legally critical eye-witness testimony is taken out of her hands by a long flashback that substitutes for the testimony in court.

[37] Whatever the variants, the most persistent theme in Hollywood film is the polarization of the woman attorney and the Justitia character. The woman attorney is inept, unaware, or morally perverse, and needs help from men or from Justitia to carry out her legal mission. Left on her own, she fails. The female figure of justice continues to be entrusted to gifted amateurs–to the waitress and victim in The Accused; to a nun inDead Man Walking (1996); to a remodeling contractor in The Hurricane(1999), where the plot also turns on the falsification of linear narrative; and in a nervous compromise, to a working-class secretary in Erin Brockovitch (2000), where we are constantly reminded that, even though she is inside a law office, she is not an attorney. While most of these films show women characters who are more assimilated than Kaitlin Costello in The Verdict--indirectly reflecting the increasing assimilation of women into the economy–the concept of justice has become more diluted as well. In two of the most recent films, the evil woman attorney in The Insider is out for money, but so is the justice-minded Erin Brockovitch (Julia Roberts), whose story is primarily about the struggle to collect damages.

[38] One less well known film, City Hall (1996) tries to break the cultural myth by locating the woman attorney and Justitia in the same character. The woman attorney, representing the family of a Hispanic policeman who was murdered, is trying to collect his pension for them. The issue of justice focuses on the mob’s attempts to smear the reputation of the policeman. As an attorney, she is a strong character, clearly in pursuit of justice, who deftly rebuts the negative assumptions made about her by male characters–assumptions that draw on the negative stereotype. She is well on her way to winning the case until she is suddenly told by the main male character, a deputy mayor, that her key witness has been murdered. That she does not already know this and needs to be told by a man is the demise of this character. At this point she recedes to the periphery of the film’s narrative and the story becomes a story of manipulation and murder centered on men in city hall. The murder of her client that opens the film likewise recedes in significance as the corpses of major characters quickly pile up and her client’s murder case is recast as the fate of a minor(ity) character. Although the film successfully characterizes the synthesis of the woman attorney and Justitia at the outset, the narrative refuses to explore the implications of such a character.

[39] The cultural myth of the woman who holds the scales of justice has certainly not been limited to film. To what extent has feminism itself ascribed to this figure? When The Verdict was released in 1982, much that was feminist was also intertwined with the values of political liberalism. Psychoanalytic feminist film theory, which developed in this period of feminism, seems to have had an unacknowledged place for Justitia. She was shielded from direct view, and probably from feminist critics themselves, because films like The Verdict were not a subject of critique. Justitia defined a cultural space that seemed to be outside patriarchal film practice, a position from which feminist theorists repeatedly denounced the indignities and victimization of women in film. Feminist psychoanalytic theory de facto constructed an outside to film theory, its own exclusionary subjectivity, for the just views of the feminist critic. Film studies presents a quite striking case, but other areas of feminism, such as the importation of French feminism in literary criticism, showed a similar pattern. At a time when most women were still marginalized in the power structure of the academy and other institutions, to what extent was the idea of Justitia the implicit basis for a feminist ethical practice and women’s rights? And to what extent was feminism perceived by others as filtered through the figure of Justitia? Discrimination lawsuits brought by women raised the issue of exclusion as an injustice (exclusion from the workplace, or exclusions within it). Although they sought justice consciously and overtly, they rarely received it. Even when women plaintiffs were successful in settlement conferences–that is, the justice of their complaint was recognized–settlement was usually contingent on the woman resigning her job if she had not already quit or been fired (Kibbey, Plaintiff’s Perspective). Justice and the exclusionary subject were made to coincide in the resolution of the case. As inThe Verdict, Justitia prevailed, but the woman lost her job.

[40] Feminists have generally thought of naturalized images as negative, patronizing, and demeaning to women, fantasies created by the patriarchal imagination to serve the interests of men, not women. In this regard, the figure of Justitia may seem to be an exception, but she is not. The Verdict is important for feminism because it shows how the image of Justitia, though it seems positive, ultimately functions in the same way. As the structure of meaning moves her to the center of its discourse, her figurative sanction also sanctions the neglect and debasement of the human being who is the bearer of her truth. Furthermore, insofar as feminism has shared a belief in the cultural myth of the woman who holds the scales of justice, it has also shared a belief in the validity of indexical meaning. There is a conservative undertow in the idea of indexical meaning, one that runs counter to the liberal emphasis on individual rights, because the function of indexical meaning is to halt the play of signifiers, to fasten on a single and invariable meaning as truth, to put a stop to the plurality of signification. This darker side has surfaced in debates about political correctness. When justice is grounded in an indexical figure, the figure itself may seem noble, but the effects of indexicality are there as well, in its capacity to function as a vehicle for censorship and as a guarantor of structural order that privileges order itself over individual rights.

Acknowledgements:

I would like to thank Marina Heung and Elayne Rapping for their insightful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Works Cited

- The Accused. 1998.

- Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Trans. Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981.

- Bazin, André, What is Cinema? Vol. 1. Trans. Hugh Gray. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967.

- City Hall. 1996.

- Clover, Carol J. “Her Body, Himself: Gender in the Slasher Film.” Ed. Sue Thornam. Feminist Film Theory: A Reader: 234-50. New York: New York University Press, 1999.

- Cott, Nancy F. The Bonds of Womanhood: Woman’s Sphere in New England, 1730-1835. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977.

- Dead Man Walking. 1996.

- Derrida, Jacques. “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences,” with transcript of discussion following the presentation of the paper in 1966 at John Hopkins University. Ed. Richard Macksey and Eugenio Donato. The Structuralist Controversy: The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press: 247-72.

- Doane, Mary Ann. Femmes Fatales: Feminism, Film Theory, Psychoanalysis. New York: Routledge, 1991.

- Erin Brockovitch . 2000.

- The Hurricane. 1999.

- The Insider. 1999.

- Jagged Edge. 1985.

- Jay, Martin. “Must Justice Be Blind? The Challenge of Images to the Law.” Ed. Costas Douzinas and Linda Nead. Law and the Image: The Authority of Art and the Aesthetics of Law: 19-35. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- Kibbey, Ann. “C.S. Peirce and D.W. Griffith: Parallel Action, Prejudice, and Indexical Meaning.” Semiotics 2001. Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth Annual Meeting of the Semiotic Society of America.

- _______. “The Plaintiff’s Perspective on the Legal Process in Gender Discrimination Cases.” Concerns 26.2 (Summer, 1989): 91-105. Modern Language Association Publications.

- Krauss, Rosalind. “Notes on the Index: Seventies Art in America,”October 3 (Spring, 1977), 68-81, andOctober 4 (Fall, 1977), 58-67.

- Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” The Sexual Subject: A SCREEN Reader in Sexuality: 22-34. London: Routledge, 1992.

- Peirce, Charles Sanders. Collected Papers. 9 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1932.

- _______. “Guessing.” The Hound and the Horn: A Harvard Miscellany. 2.3 (1929): 267-82.

- Reed, Barry. The Verdict. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1980.

- Rose, Jacqueline. Sexuality in the Field of Vision. London: Verso, 1986.

- Serpico. 1973.

- de Saussure, Ferdinand. Course in General Linguistics. Ed. Charles Bally, et al. Trans. Wade Baskin. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966.

- Silverman, Kaja. The Acoustic Mirror: The Female Voice in Psychoanalysis and Cinema. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988.

- The Verdict. 1982. Dr. Sidney Lumet. Sc. David Mamet. Ac. Lindsay Crouse, James Mason, Paul Newman, Charlotte Rampling.

- Wollen, Peter. Signs and Meaning in the Cinema. 3rd ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1972.