Environmental justice and waste in the Denver metro area

The environmental justice movement seeks to achieve equal distribution of the environmental benefits and burdens of economic growth. This movement began in the 1980s, when Robert Bullard did research regarding race and pollution. He found “race to be the single most important factor (i.e., more important than income, homeownership rate and property values) in the location of abandoned toxic waste sites” and that “three of the five largest commercial hazardous waste landfills are located in predominately African American or Latino communities and accounts for 40 percent of the nation's total estimated landfill capacity (Bullard, 160)."

These findings are the result of redlining and zoning.

- Redlining is a discriminatory practice that has denied loans and services to BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and Persons of Color) communities for centuries. This has pushed BIPOC communities out of neighborhoods with stricter environmental regulations, allowing them to be exposed to toxic landfills that negatively affect their health.

- Zoning laws more often than not “shortchange” communities of color by labeling their neighborhoods as “industrial” areas where there are fewer environmental regulations. This allows companies to place dangerous sites such as municipal landfills in close proximity to their homes (Bullard, 161).

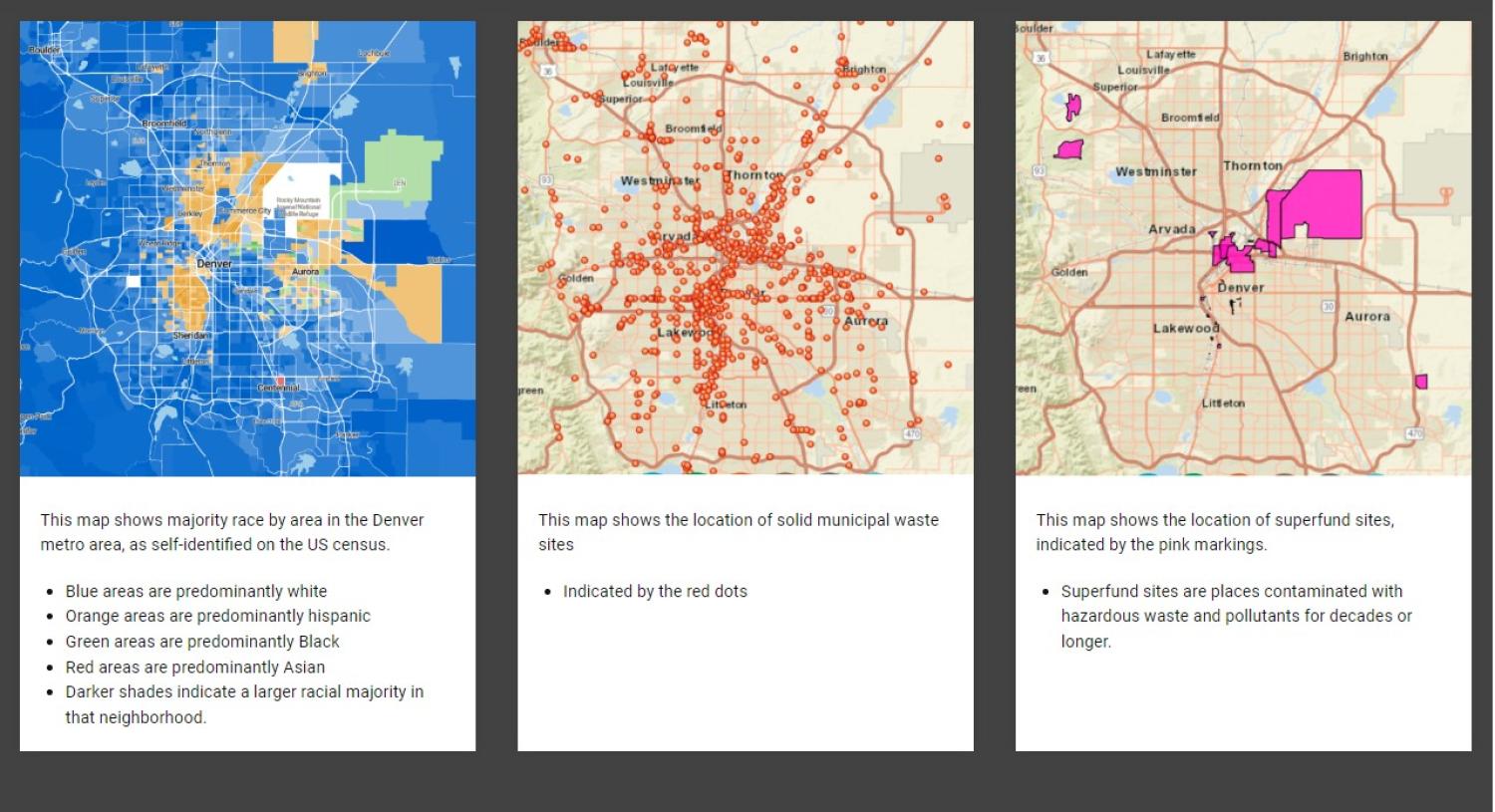

This article explores race in relation to landfill and superfund site locations in the Denver metro area.

What can we see?

When we compare these maps, we can see that solid municipal waste sites and superfund sites are more concentrated near neighborhoods that are predominantly Black or Hispanic.

What are the implications of living near a landfill/superfund site?

Environmental impacts of landfills

- Air pollution

- Water pollution

- Soil pollution

- Noise pollution

Health effects of pollution

There are many health costs to living in close proximity to landfills, including:

- Cancer

- Respiratory illnesses

- Cardiovascular illness

Waste reduction helps communities targeted by pollution

- By reducing your waste, you can help keep harmful pollutants out of these areas.

- You can reduce your waste by refusing to use single-use plastics, composting food waste and paper products, re-using whenever you can, only buying what you need, and recycling correctly.

- Make sure you’re disposing of your waste properly by taking our America Recycles Day quiz!

Sources

Bullard, Robert. “Environmental Justice in the 21st Century: Race Still Matters.” 2015. PDF file.