Musings on "Disparate puntual, Una Reina del circo"

For our February newsletter, I began the process of searching through our collection hobbled by an abundance of choice. We have so many good things to choose from; so many different ideas are spawned by encountering as many objects as we have here. What was I to do? For me, this was a paralyzing problem and in desperation I started simply scrolling through our entire catalogue. I was hoping to be struck by a bolt of inspiration while vaguely formulating a sense of direction for my writing.

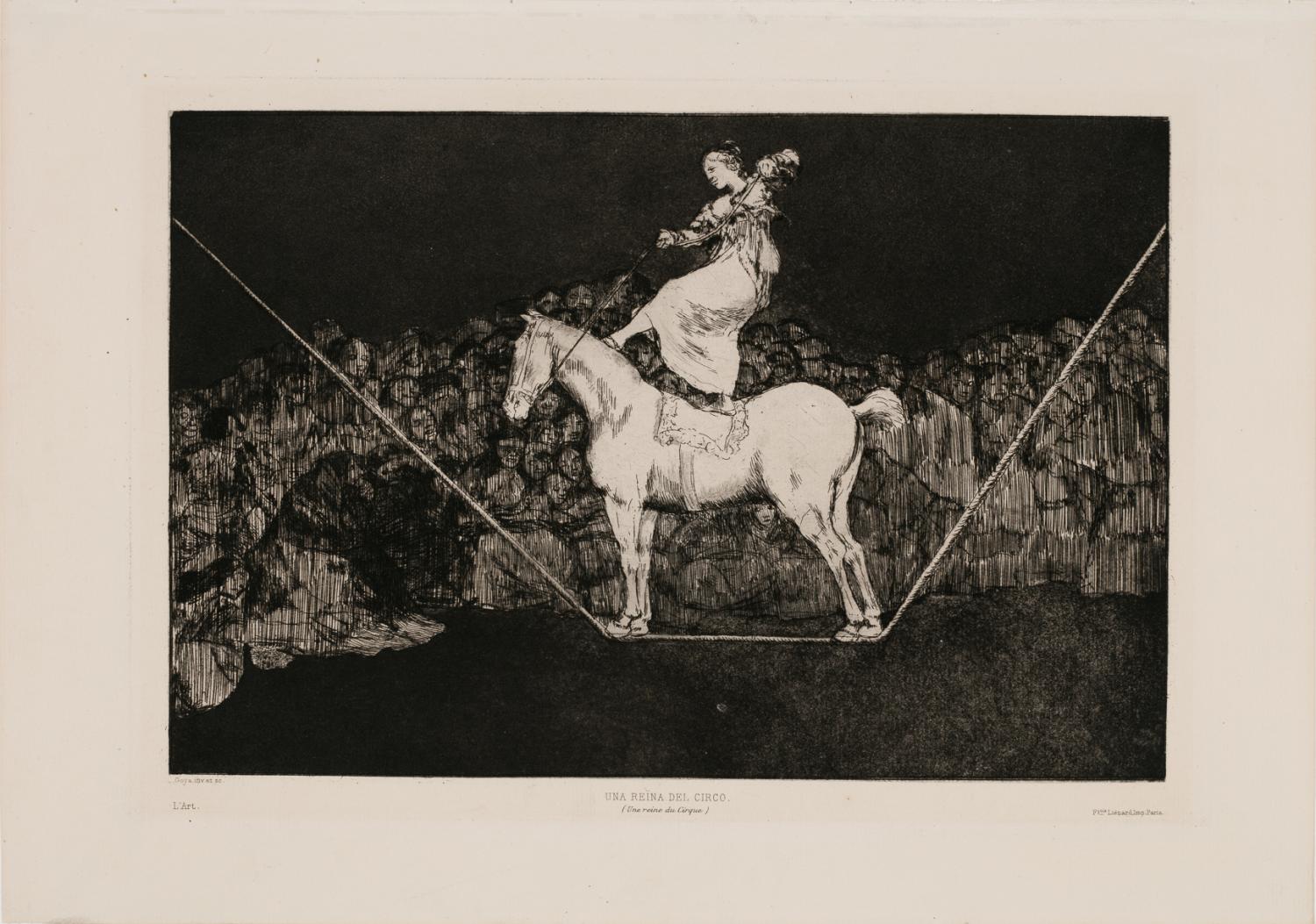

Maybe the absurdity of my approach is one of the good things about having access to our collection’s database, because the idea of reflecting upon absurdity itself came upon me and in that instant...Goya! Selecting Goya’s Disparate puntual, Una Reina del circo (Punctual Folly or The Queen of the Circus), from the series Los Disparates (Los Proverbios) (The Follies) seemed perfect. The concept of “Disparate puntual” felt timely and its appearance before my eyes well, punctual.

Before I proceed, I should explain the meaning and use of the Spanish word “disparate” as distinct from its English spelling twin “disparate”. In Spanish, a “disparate” (dees-pah-rah-teh) is just a touch more than folly; less innocent, more willful, committed by someone who really should know better. It is an absurdity of such profundity, a ridiculousness so ridiculous that it deserves nothing but ridicule. In Spain, a true “disparate” is often swiftly met with mockery, reprimand or exasperation. The second word, “puntual”, refers to something or someone being on time or timely.

What I see in Disparate puntual, Una Reina del circo is a simple allegory, yes, but also a total “disparate”. A royal figure atop a powerful but helpless horse, she’s on the verge of tipping over, working against all odds to stay mounted on her throne. How could a queen possibly have gotten herself into this position? Her predicament is absurd, ridiculous, pure circus, and she’s done it to herself! It is an impossible balancing act done without the safety net of her subjects who appear either powerless or unwilling to throw themselves under her and prop her up. She’s bound to fall hard, and all anyone can do is watch; wait to either laugh or cry. Regardless of perspective, it is unlikely that anyone reading this today would have to strain their imagination for this kind of “disparate” to look a little familiar.

Context is important, and just as we are now, Goya was living through a mercurial era. During the earlier years of his life, his world was marked by the slow contraction of the Spanish Empire, the adoption of Spain’s liberal Constitution of 1812, by Enlightenment thought colliding with the Roman Catholic Church and the Monarchy’s traditional power structures. One needn’t guess at the types of socio-political conflict brewing in such a climate. In mid-life, he survived a mysterious and severe illness that caused hallucinations, migraine, loss of balance. His illness kept him mostly bedridden for about two years, and it left him permanently deaf. Late in his life, these transformational elements were punctuated by Napoleon’s conquest of the Iberian Peninsula. After Napoleon’s ouster and an interventionist boost from French Royalists, came the repeal of the Constitution of 1812 and the absolutist reign of Spain’s King Ferdinand VII which drove Goya, now approaching the end of his life, to seek refuge in France where he remained until his death.

What happened in Spain while these volatile mixtures of ideology and power jockeyed for dominance is what always happens anywhere else in the world, and Goya bore witness to many atrocities, to many absurdities, and to much ridiculousness. The experiences of his life brought into full view the range of human capacity in all its stark contrasts. As many artists are wont to do when confronted with “disparates” he responded with images of mockery, horror, ridicule, exasperation. In so doing, he raised up in appeal to our humanity both a lens and a mirror with the capacity to transcend time. He asks us to both observe and reflect. So, when I am considering the historical context and the political climate within which Goya produced Disparate puntual, Una Reina del circo, I cannot help but see some similarity to conditions and behaviors of our own time. I am also forced to confess that I myself play a role.

Selecting Goya seemed fitting for another more personal reason. I have deep family ties to Spain. My father is Spanish, and until I was six years old, I lived in Madrid. There, I was surrounded by the buildings, monuments and markers of Goya’s time; in a sense by Goya himself. The Prado Museum was a short bus ride away, and I visited the galleries containing his works many times. His printing studio is preserved as a small museum not very far from Madrid’s main square, the Plaza Mayor. But I also remember the experience of being a young child in a tumultuous Spain, one still under Francisco Franco’s rule after the brutal civil war little more than 30 years earlier. I remember the events unfolding in the power vacuum left after his death, and the bizarre transition back to monarchy. In the news and on the faces of the adults around me, I saw the effects of political upheaval, power struggles, coup attempts, ETA bombings...the “disparates” unfolding in the very same city where Goya lived and worked over 150 years earlier, surviving and processing the absurdities of his own day.

I feel so fortunate we have this print in our collection, to have it be able to communicate with us viewers across time and speak to those shared aspects of our humanity. Despite differences, we can all recognize a “disparate” when we see one, and our reactions are almost universally similar. Seeing it before me now, I can appreciate that Goya’s Disparate puntual, Una Reina del circo is, for me at least, still serving its intended purpose. Goya’s print links me to my own cultural heritage and to my past, yes, but it is relevant to my future since how I choose to respond to the “disparates” of my present paves a path forward.

I hope the readers of our newsletter will feel inspired to seek out and reflect upon the Goya prints in the CU Art Museum’s collection. For some extra fun, and to get a larger sense of the “disparates” of Goya’s time, try exploring the historical context in which these prints were created. I’ll wager you’ll find many parallels in today’s world. Any of the events I mention earlier in this writing would make good points of departure for your journey!

Image credit: Francisco de Goya, Spanish (1746–1828), Disparate puntual, Una Reina del circo (Punctual Folly or The Queen of the Circus), from the series Los Disparates (Los Proverbios) (The Follies), 1816-1824, published after 1877, etching and aquatint, 11 15/16 x 16 7/8 inches. Gift of Anna C. Hoyt, CU Art Museum, 57.169. Photo by Wes Magyar, © CU Art Museum