Unlearning Pain

Can chronic pain patients think themselves into wellness? An unprecedented brain imaging study aims to find out.

Cheri Gould doesn’t remember exactly when the pain first began to creep across her shoulders, down her spine and into her back. To this day, she’s not sure what started it.

But she remembers what life was like before.

She played soccer and softball, ran regularly and was full of energy and drive.

“I have never been one to let things stop me,” she said.

But after 12 years, multiple diagnoses and futile tries at everything from physical therapy and Botox injections to opioids, the 48-year-old mom and teacher — like many of the 100 million Americans suffering from chronic pain — has grown weary of the way pain interferes with her life, and desperate for nondrug, nonsurgical treatment options.

“I’ve heard a lot of talk about tapping into the mind-body connection, but I am a science person. I need evidence,” she said, before slipping on some blue scrubs, lying flat on her back inside a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine, and letting a team of neuroscientists peer inside her brain. “That’s why I’m here.”

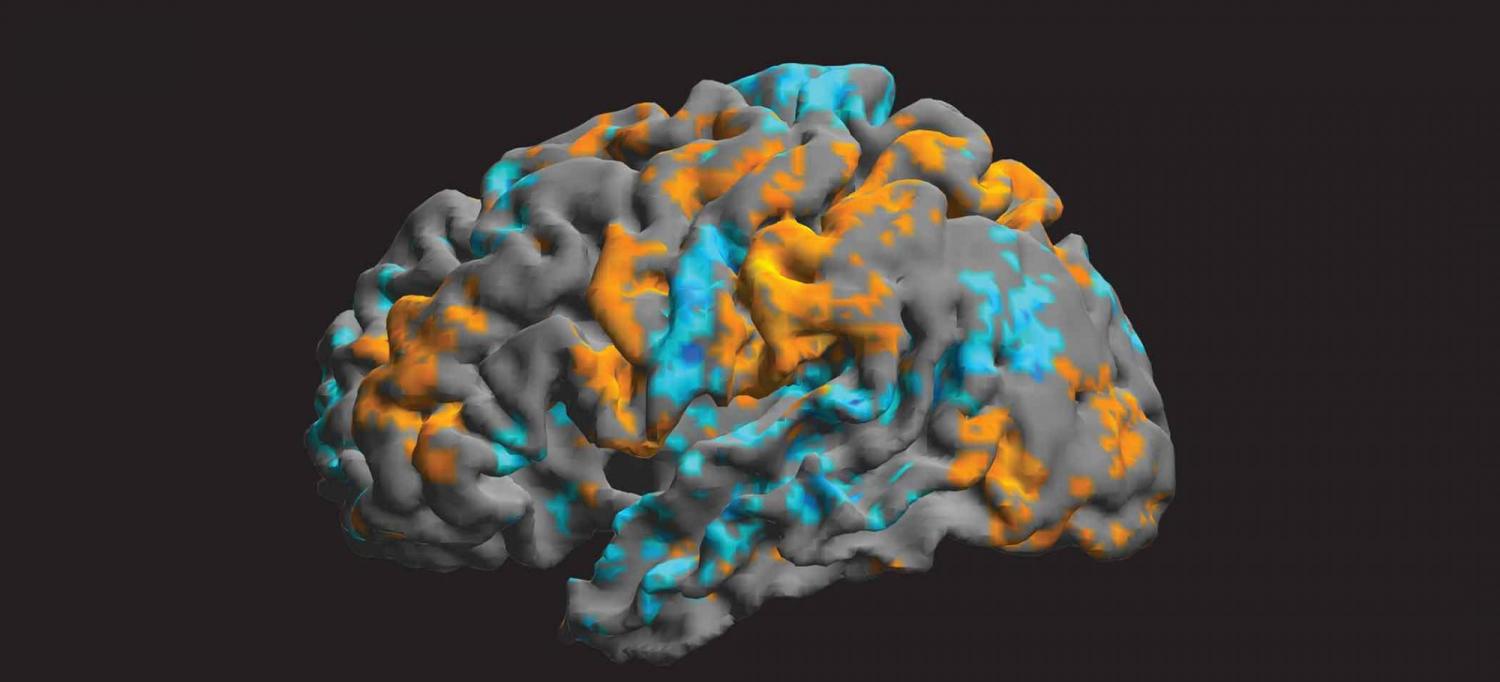

Study subjects’ brains reacting to a knife scraping a glass bottle.

Gould is among 150 or so chronic back pain patients who made their way to CU Boulder last summer for the largest brain imaging study ever to explore mind-body treatments for chronic pain. The study hinges on a question that spiritual practitioners have been asking for centuries: Can thoughts and emotions have a measurable impact on physical well-being?

CU graduate student Yoni Ashar (PhDNeuro, PhDPsych’18), a former software engineer who made his way to neuroscience via his own spiritual quest, is now asking an even more specific question:

“Can we think ourselves out of chronic pain?”

"The assumption for a long time has been that chronic pain is driven by problems in the body. The neck. The back. The tissue," said Ashar, who is leading the study.

“But there is a paradigm shift underway. People are realizing that for many patients, the brain is at the center. To get at that pain, we have to change the way we think and feel about it.”

Meditating Monks

Eight years ago, Ashar was sitting in a synagogue in Jerusalem watching a slide presentation of red-robed monks having their brains scanned when he realized what he wanted to do with the rest of his life.

Bored and unsatisfied, he had quit his job as a computer scientist in Washington, D.C., in his early 20s and moved to Israel to study spirituality.

He considered becoming a rabbi.

But as he heard the presenting neuroscientist explain the clear changes that occurred in monks’ brains as they meditated, something clicked.

“I had zero background in psychology. I had never taken a neuroscience class. But I remember feeling electrified at the thought that you could use scientific tools to study these things I had been reading about in spiritual texts,” he said.

Ashar scoured the internet looking for the world’s leaders in functional MRI research, which maps blood flow in the brain to examine neural activity. He emailed a dozen of them offering to work as a software designer to get his foot in the door.

Tor Wager, director of CU Boulder’s Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience Lab, emailed him back.

Today, Ashar is finishing up dual doctorates in neuroscience and clinical psychology and has shifted his focus from how spiritual practices alter the brain to how thoughts and emotions impact its pain-related regions.

He points to numerous recent studies suggesting that, even in the absence of tissue damage, misfiring neural pathways can cause or perpetuate pain.

“The brain learns to be in pain,” he says. “But can it be unlearned?”

In one famous case study, a construction worker arrived at an emergency room with a 6-inch nail protruding from his boot, the pain so excruciating he had to be sedated. When the boot came off, doctors discovered the nail had passed between his toes, never puncturing him.

Other recent studies have shown that sham surgeries — in which the patient is sedated and a surface-level incision is made — can be as effective for pain relief as real ones.

Another paper, published in 2013, showed that while acute pain from a tissue injury lives in a region of the brain commonly associated with pain (what Ashar calls the “I just stubbed my toe” region), chronic pain resides in a different region — one closely associated with reward and emotion.

That could help explain why some chronic pain sufferers feel their symptoms flare up around a mean boss or an estranged relative, Ashar said.

“Pain is a danger signal that tells you to stop what you are doing so you don’t do more damage. But sometimes these danger signals can be activated even in the absence of injury,” or linger after the injury is gone, said Los Angeles-based pain psychologist Alan Gordon, who is collaborating with Ashar on the study.

Added Ashar: “It’s like a false alarm that is stuck in the ‘on’ position.” That is not to say the pain is “all in your head.”

“There is no such thing as imaginary pain,” Gordon said. “If you feel it, it is real.”

Shutting Off the Alarm

Basic structural MRI image of Yoni K. Ashar

Over the past 10 years, he has worked with hundreds of patients with intractable chronic pain, using mind-body methods to help them shut off the false alarm, after ruling out serious structural causes.

For instance, if someone always experiences pain when they sit, Gordon might ask them to sit slowly, paying close attention “in a detached, curious way” to how this feels physically and the fearful thoughts that come with it, and to evaluate whether those fears are justified.

After a few repetitions, the pain often lessens.

“The goal is to break that learned association — to teach the brain that something they learned to interpret as dangerous is actually safe.”

While he has seen such methods work time and again in his own practice, he realizes that it will take scientific evidence to convince the broader medical community.

That’s where CU Boulder comes in.

“Tor and his team are among the most respected groups of scientists in the world when it comes to fMRI studies,” he said. “We are really excited to be working with a group with so much credibility.”

Your Brain on Pain

On a recent July day, Gould was lying on her back inside a tube-shaped $2 million MRI machine at the Intermountain Neuroimaging Consortium facility on the Boulder campus clicking a button near her right hand to rank her pain as researchers remotely applied pressure, first to her lower back, then to her thumb.

Three-dimensional images of her brain appeared on the screen before them, providing detailed baseline information about which regions light up during pain, and by how much.

Over the course of the study, she and the other participants would be assigned to one of three treatment groups exploring noninvasive, nondrug approaches to treating pain.

A month later, they would have their brains scanned again.

Ultimately, the researchers hope the project will accomplish two goals: First, they hope to develop a brain marker, or signature, which doctors can use to assess a patient’s pain. (State-of-the-art measurement today, believe it or not, involves asking patients to rank their pain from 1 to 10 or choose from a series of sad-to-happy faces.)

Second, they hope to use the brain scans to assess scientifically just how effective psychological treatments are, and precisely how they work.

Published results are months away. But in the end, the research could change lives.

Said Ashar, “We think this study stands to make a large impact on the field and on the treatment of chronic pain in general.”

Comment? Email editor@colorado.edu.

Photos by Yoni Asher