Invisible Manuscript Appears

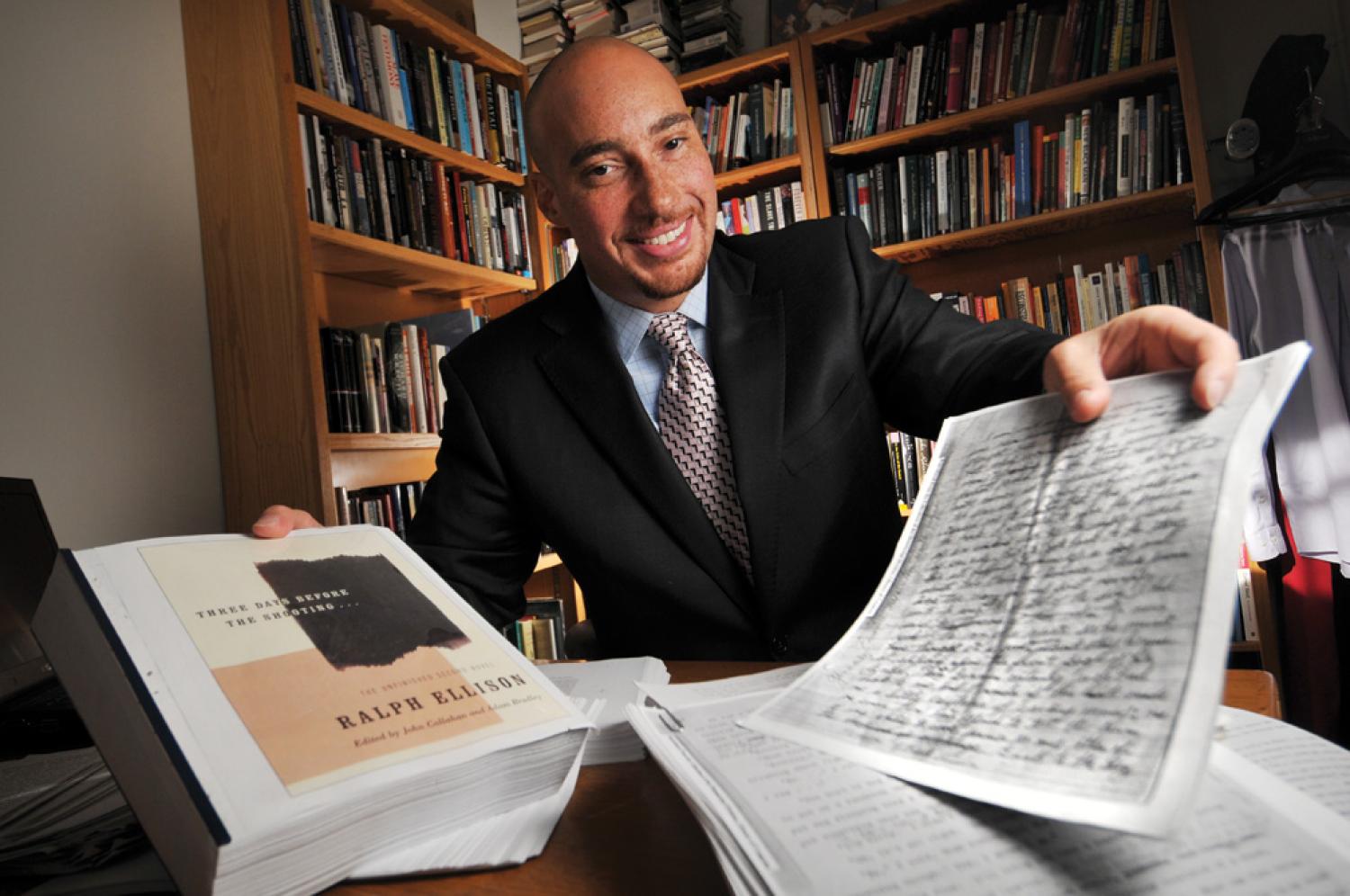

CU associate professor Adam Bradley of English spent 15 years sorting through author Ralph Ellison’s manuscripts to piece together the author’s unpublished second novel. Bradley and professor John Callahan of Lewis and Clark College published Three Days Before the Shooting. . . (Random House) in January 2010. Photo courtesy Glenn Asakawa.

Ralph Ellison published his groundbreaking Invisible Man in 1952 but died before finishing his long-awaited second novel. Against all odds, CU’s Adam Bradley and a colleague pieced together Ellison’s manuscripts, publishing the opus in January.

Author Ralph Ellison closes one novel and foreshadows another with a puzzling question:

“Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?” Concluding his harrowing tale of the life of a black man in 1930s America, the nameless protagonist of Invisible Man makes a bold query. How, after all, could a marginalized voice speak for a diverse and divided nation?

Fifty-eight years after the novel’s publication, Adam Bradley, an associate professor of English at the University of Colorado, is helping to reveal what else that potent voice — and its creator — would have said. In January, Bradley and co-editor John Callahan of Lewis and Clark College in Portland, Ore., released Ellison’s unfinished second novel, Three Days Before the Shooting . . . (Random House), after spending 15 years compiling scores of Ellison’s drafts.

Invisible Man (Vintage), published in 1952, catapulted Ellison to a life of great fame and expectation. In 1953 the novel won the National Book Award, beating Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea (Scribner).

Immediately hailed as an important work and now revered as an American classic, Invisible Man raised hopes about what Ellison himself promised — a second novel. But while Hemingway, William Faulkner and James Baldwin produced steady streams of books, short stories and plays, Ellison’s creativity seemed to ebb. Some speculated that Ellison was paralyzed by self-imposed pressure to craft an epic work.

Years and then decades ticked by. In 1994 — 42 years after his first novel appeared — Ellison told The New Yorker that he was working every day on his second novel and that “there will be something very soon.”

Two months later, pancreatic cancer claimed Ellison’s life and, with it, readers’ hope for the new novel.

Becoming a literary archaelogist

But Ellison’s friend Callahan, literary executor of the author’s estate, was determined to publish Ellison’s second novel, which was not, despite what Ellison had suggested, in near-final form.

As Bradley and Callahan note in the book’s introduction, Ellison left behind “a series of related narrative fragments, several of which extend to over 300 manuscript pages in length, that appear to cohere without truly completing one another.”

The work was voluminous: 27 boxes of archived material in the Library of Congress, thousands of manuscript pages and 469 computer files on 84 disks.

Bradley joined the effort at Lewis and Clark College in 1992 as a student of professor Callahan, who by 1994 needed help making sense of the sprawling work Ellison left behind. While Callahan would publish the 348-page Juneteenth (Random House) in 1999 based on one section of the manuscript, he noted in his afterword that the full book would follow. And that’s where Bradley would play a large role.

Born in Salt Lake City in 1974, Bradley was primed for this task by nature and nurture. When he was in first grade, Bradley’s teacher told his mother that the child couldn’t read and that he “just isn’t that bright.” The boy’s mother, who viewed this as nonsense, took Bradley out of school. His grandmother home-schooled him for the next nine years. From her, he learned Shakespeare, Keats and Coleridge.

Bradley, it turned out, read rather well. And he had a special affinity with Ellison, whose father died when he was a child, whose first novel vivified America’s racial divide and whose unfinished second novel centered on a race-baiting senator of “indeterminate race.”

Bradley’s own father did not raise him. His mother is white, and his father, now deceased, was black.

Photo courtesy U.S. Information Agency.

On several levels, Ellison spoke to Bradley. Ellison’s second novel dwells on paternity, race and the democratic promise of America. A senator is assassinated by a black man who, it turns out, is the senator’s son. The senator’s surrogate father, who is black, tries in vain to save the senator.

These themes struck chords with Bradley, who, as a student, became a literary archaeologist.

Callahan was so impressed that he asked Bradley to co-edit the second novel. Before Bradley could devote himself fully to the project, though, he established his academic credentials. He earned his Ph.D. in English and American Literature and Language from Harvard University in 2003.

As Bradley notes, his concentrated work on Three Days Before the Shooting. . . began soon after the turn of the 21st century and continued until “just about now.” There was much to sift and sort.

History as a backdrop

In 1982, Ellison said the goal of his second novel was to achieve “the aura of summing up,” of rendering the full complexity of the American experience on the page.

“That’s a lofty aim,” Bradley observes. “Essentially he’s talking about writing the great American novel.”

Like the novel itself, America changed greatly during the second book’s gestation. Ellison began writing his new work before 1954 when the U.S. Supreme Court found segregated public schools unconstitutional.

In 1967 a fire destroyed Ellison’s home and perhaps 300 pages of his manuscript. Ellison said the loss was significant. But he kept writing.

In 1982 — one year before President Reagan signed a bill establishing Martin Luther King Jr. Day — Ellison bought the first of three personal computers he would acquire by 1988.

A 2007 Washington Post story notes Callahan was mystified by the fact that Ellison had written scenes to “near perfection” in the ’50s and ’60s but revised them extensively a quarter-

century later on the computer.

Bradley, who grew up in the digital age, thinks Ellison became transfixed by the computer’s power to move paragraphs, insert words and delete whole sections. Ellison was a technophile, and “the shifting and shaping of his second novel became a new kind of mania,” the Post reported.

There may have been a method in the maddening array of rewritten episodes, fragments and character and plot outlines made by hand, on typewriter and finally on computer. But the author’s ultimate aim was elusive. And Ellison left no instructions on what should be done with his work.

This was a literary jigsaw puzzle in legions of bits and bytes.

“The first thing we did was to understand the totality of things . . . what we had and what we didn’t have,” Bradley says. Step two was organizational, trying to give shape to the material.

Unsettled ending

Based on their best assessment of Ellison’s intent, Callahan and Bradley assembled the novel, which is unfinished and unresolved. A reader should expect to assume unusual responsibilities, Bradley says. “One of them, I don’t think it’s too much to say, is to act as co-creator of the fiction.”

Ellison composed episodically — crafting scenes one after another and often rewriting entire episodes, sometimes with different endings or from different perspectives. The novel includes episodes not yet fused that approach a conclusion not yet settled.

One value of this book is that readers can see how a literary masterpiece takes shape, Bradley adds.

“You can only learn so much about the craft of fiction by studying classic novels alone,” he says. “In fact, you often learn more by reading imperfect fiction because the seams show.”

Bradley and Callahan edited the material for a general audience, not simply for scholars.

“We decided we wanted to keep with the democratic spirit of Ellison’s writing. . . so that everyday people could pick it up and enjoy it as fiction,” Bradley says.

They did not pepper Ellison’s text with footnotes but isolated their commentary to introductory notes. “If someone wants to read only Ellison, they can do that,” Bradley says. Every word of fiction in the book is Ellison’s, the editors emphasize.

T.S. Eliot, one of Ellison’s favorite poets, once wrote, “In my end is my beginning.” It is no accident, Bradley suggests, that the second novel addresses the question posed at the end of Invisible Man: “Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?”

But unlike Invisible Man, which has one narrator,Three Days Before the Shooting . . . reflects several perspectives.

“You get all of these voices, and it seems as if Ellison wanted to populate his novel with as much of America as he could,” Bradley says.

“Ellison was writing a novel concerning betrayal and redemption, black and white, fathers and sons,” the editors write. “It is a novel that takes as its theme the very nature of America’s democratic promise to make the nation’s practice live up to its principles . . . regardless of race, place or circumstance.”

Bradley, who joined CU last year, is the author of Book of Rhymes: The Poetics of Hip Hop (Basic Civitas Books) and is co-editor of the forthcoming Yale Anthology of Rap. Later this year Yale University Press will publish his second book related to Ellison, Ralph Ellison in Progress, which is a critical exploration of the craft of Ellison’s fiction.

Bradley says being able to publish Ellison’s second novel while at CU is particularly meaningful, “because the relative racial homogeneity of our community makes it possible to sidestep some of the challenging issues Ellison’s novel brings up. Reading the book denies us that evasion.”

And who knows? On the lower frequencies, Ellison might speak for us.