When Sputnik and the Beatniks Ruled

During the late 1950s, Bob Harvey (Edu’59) and his friends at the University of Colorado listened to folk artists like the Kingston Trio, played guitar and ruminated on the deeper meaning of Jack Kerouac’s 1957 anti-establishment treatise, On the Road (Viking).

“I remember one guy who read the entire book in one night,” says Harvey, who managed to have both Greek and Beatnik friends. “In the morning he packed his suitcase and left. No one ever knew what happened to him.”

The ’60s were but a New Year’s toast away, and World War II and the Korean War were still fresh in the nation’s collective memory. But for a few brief years on campus, the world’s troubles seemed far away.

“It was an island of innocence … a period of time I often refer to as a long summer afternoon,” recalls Harvey, 71, a retired educator and cartoonist.

On May 7, Harvey will join other 1959 graduates to commemorate an era many students, faculty and historians fondly recall as remarkably peaceful on campus. It was a time when dress codes and curfews — not social reform or global terrorism — were the hot political topics among students, protests were few and far between and a carefree, somewhat “naïve” mindset prevailed.

It also was a critical time in CU’s history as President Quigg Newton worked to raise admission standards, recruit more forward-thinking faculty and transform CU from a modest regional college to a nationally recognized research university. And, according to some, it represented the calm before the ’60s storm, as the Beatnik culture — the precursor to the hippie movement — began to quietly gain momentum.

When Linda Lacy Johnson (Engl’59) left Texas in fall of 1955 to attend CU, the school hosted just over 11,000 students compared to more than 29,000 today. Tuition was $150 for a nine-month academic year for residents, $544 for nonresidents compared to $4,617 per semester for residents today and $12,700 per semester for nonresidents. And the campus building boom was yet to come.

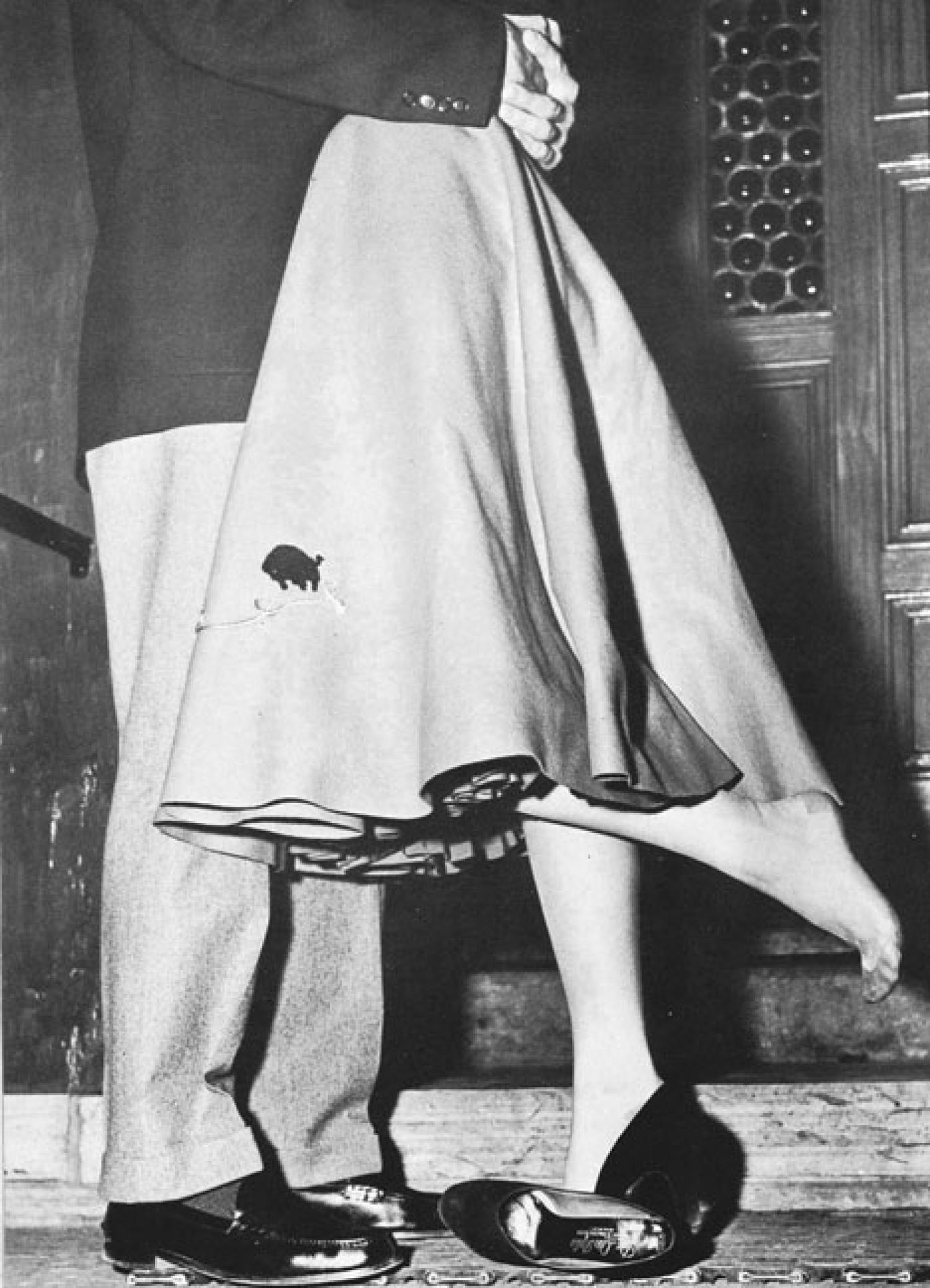

Like many new students, she quickly found a home in a sorority (Delta Gamma), where pleated skirts, cashmere sweaters and saddle shoes were high fashion, the notion of a cell phone was unfathomable and the rules were strict.

“In the sorority house we had two phone lines for 80 women and a bell system to get you if you had a call,” she says. “We had to be in at 9 p.m. on weeknights and 10:30 p.m. on weekends and we couldn’t wear jeans or slacks.”

That’s not to say the class of ’59 didn’t know how to have fun. Johnson and her friends gathered at the smoke-filled Sink where actor Robert Redford (A&S ex’58, HonDocHum’87) worked. They danced the jitterbug at Tulagi, headed to Erie — just outside of “dry” Boulder where only 3.2 beer was allowed — and ordered up a stiff Scotch at the Bali Hai bar.

Students listen to their peers strum their guitars in this photo from the 1960 yearbook.

In spring, during the infamous bacchanalia called the “Mudeo,” even the most prim sorority girls would slip on long pants with the letters of their boyfriend’s fraternity emblazoned on the rear and participate in co-ed trike races in a giant mud-filled field on campus. They had to be hosed off afterward.

“My kids still can’t believe I did that,” says Johnson, 70, a mother of four who lives in Boulder.

The large Greek population aside, another social group was flourishing.

“There were two distinctly different and almost mutually exclusive social milieus on campus,” Harvey says. “One was the button-down crowd. The other was the Beatniks.”

Clad in a corduroy blazer, a black shirt and a bolo tie, Harvey says he was considered “pretty far out” by his fraternity brothers.

On Oct. 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched the world’s first artificial satellite, Sputnik I, hurtling the space race into high gear and sending college administrators and professors scrambling to become leaders in science and technology.

President Newton, who had taken office in 1956, rose to the challenge by increasing faculty salaries by 75 percent during his term, actively recruiting distinguished scholars from across the country and requiring prospective students to take the SAT. He helped establish new scientific institutions like the Institute for Behavioral Sciences and a nuclear physics laboratory and built new residence halls, new law and chemistry buildings and the Wardenburg Student Health Center.

“It was a time period that really shaped this university into a modern research university,” says Kay Oltmans (MComm ex’75), director of the CU Heritage Center, the history museum.

Violet Lee Hunt (Chem’59) vividly remembers the day she decided to switch her major from journalism to chemistry.

“It was right after Sputnik,” she says. The professor was passing back our tests in order — best grade to lowest grade. He said, ‘Those of you in the top third should consider going into the physical sciences. We need all the people we can get.’ I took it personally.”

At a time when most female students gravitated toward teaching, nursing or home economics, Hunt became one of two to graduate with a degree in chemistry in 1959.

“The university was extremely encouraging,” she says. “Never once did I feel like I couldn’t do it.”

While the ’50s were mild compared to what was to come, they were not without controversy.

“I remember when Richard Nixon and his wife came and spoke at Macky in 1957,” Hunt recalls. “Students from the Democratic Students Association marched right down the aisle with their horns and banners and had to be ushered out.”

That same year a publication titled Young Socialist — the Voice of American Radical Youth began appearing on campus, raising alarm among conservatives who criticized Newton for creating an environment of “left wingism” on campus. Soon Newton was lambasted for inviting physicist Frank Oppenheimer, younger brother of J. Robert Oppenheimer (the “father of the atomic bomb”) and reportedly a former member of the Communist Party, to teach at CU. He arrived at his post nonetheless and become a well-respected professor. In 1959, Ken Penfold (Mktg’37), director of the Alumni Association, resigned because, among other reasons, he believed CU had “too many communistically inclined persons.”

Other controversies seemed to hint at the unrest to come. In 1958, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) protested the homecoming theme “Little Bit of Dixie” and “Cotton Pickin’ Ball.” At least one sorority was kicked off campus for refusing to admit a racial minority pledge.

One year later, famously liberal sociology professor Howard Higman (Art’31, MSocSci’42), the founder of the Conference on World Affairs, engaged in a heated classroom debate with conservative student and 1958 Miss America Marilyn Van Derbur (Engl’60) about the tactics of J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI. According to Time magazine, the contentious discussion went on for two days, dividing students along political lines and earning Higman a thick FBI file.

“By our senior year the editors of the Colorado Daily had started writing a lot of editorials about international politics, and we were like, ‘man.’ We had never encountered anything like this before,” recalls Harvey. “This was really grown-up stuff.”

Change was coming.

On June 5, 1959, Hunt, Harvey and Johnson joined their classmates on Folsom Field to pick up their diplomas, eat a celebratory meal of baked ham and au gratin potatoes and say their good-byes before heading out into that “grown-up world.”

Within months, Harvey would be in uniform, living on a U.S. Navy ship. Hunt would be starting a new job with the National Bureau of Standards. Johnson would be starting a family.

And CU’s “long summer afternoon” would draw to a close.

The class of 1959 reunion will be held May 7-8. Read more about it on Page 58.