Leo Streeter

Leo Streeter was born in Duluth, Minnesota, in 1918. He has lived in Chicago, Wisconsin, Texas, Oregon, and Colorado. He married and had three children and worked for Dow Chemical for most of his career. He also served in both the Army and the Navy. He has a seventeen-year-old granddaughter who is an accomplished artist. He recently moved to Boulder, Colorado and is presently living at The Academy.

My First Car

Leo Streeter (right) with his 1923 Ford Model T sedan

Click image to enlarge

Two high school boys sat on a porch one morning pondering on the question of “what should we do today?” It was getting to the end of summer (circa 1939) and we were running out of ideas. We sought activities that were fun and didn’t cost anything.

I said that I smelled smoke when I got up, probably a fire south of town, maybe in Solon or could be Gordon. Hey, we’re hearing cowbells. That means the forestry people are going through town with a flatbed truck picking up firefighting volunteers. The truck was on our street in no time and it slowed down enough so we could jump on safely. There were twenty or so volunteers already on the truck.

The fire was almost forty miles south of town in a pine forest. We knew the rules–stay out for twenty-four hours and the state sent you a check for $4.80 and provided eats–baloney sandwiches and coffee.

At the scene, Willie was handed a shovel and my task was to fill water spray cans from a nearby creek. It was a little scary and dramatic! Branches of burning pine were breaking off and the wind was carrying them into the forest resulting in new fires. It was hot and smoky. Later in the night we were told to relax; the fire was under control.

In our haste that morning we forgot it gets cold in northern Wisconsin at night. I was alone at the creek and fortunately found a sweater in a pickup truck. A big black Labrador knew it wasn’t mine and wrestled me for it until we both went to sleep on a pile of hay. In the morning we got our sandwiches, someone took our names and addresses, and back on the truck to home. For once the state was prompt and we got our $4.80 checks in a couple of weeks.

Later on, early one morning, Willie pounded on my door all excited and waving a newspaper. The local Chevy dealer had a “come-on” ad. The main headline was a car for $9.50. The specifics were lacking but we took off to check it out. We still had our firefighting money ($9.60) so we were in the running.

We weren’t the first to get to the car but those ahead of us were laughing and shaking their heads. The prize was a 1923 Ford Model T sedan. Others could laugh but it looked awfully good to us so we bought it. Willie was a natural tinkerer so it was running good in no time. A little noisy and a little smoky but it was forgiven.

Our adventures started immediately. Three or four days on the south shore of Lake Superior. A few more trips over the range and into the country. I have forgotten our meals but I’m sure there were a lot of baked beans and fruit. Gas was cheap and the car got twenty miles to the gallon. Lodging was free. We slept in haystacks and old barns in the deserted farms that were numerous in the county.

One of our buddy’s grandparents were Swedish pioneers and their original log house was in good repair so we enjoyed camping there. Camping and daydreaming. The cabin was on Ox Creek. Ox Creek flowed into the St. Croix River. The St. Croix River flowed into the Mississippi. So with a little imagination we were down in New Orleans.

The neighborhood girls refused to ride in old Nellie, as we called our car, but years later, Willie married a farm girl we met when we stopped on a farmyard to get some water.

That fall I started college at University of Wisconsin and lost track of the old model T but the memories have lingered on.

When I Was Eleven

At first it was a great cultural shock moving from a nice apartment in Chicago, Illinois, to a rundown farmhouse in Superior, Wisconsin, but we adapted almost immediately. Our new home, being in the country, had no electricity, running water or indoor facilities, but my mother and two brothers and I rose to the occasion. The early spring was cold so we had to gather a lot of firewood from a pine forest in the back of the house. Some nights were so cold that we all sat around the heater wrapped in blankets because it was warmer than being in bed. But as soon as it got warm, we started our own garden.

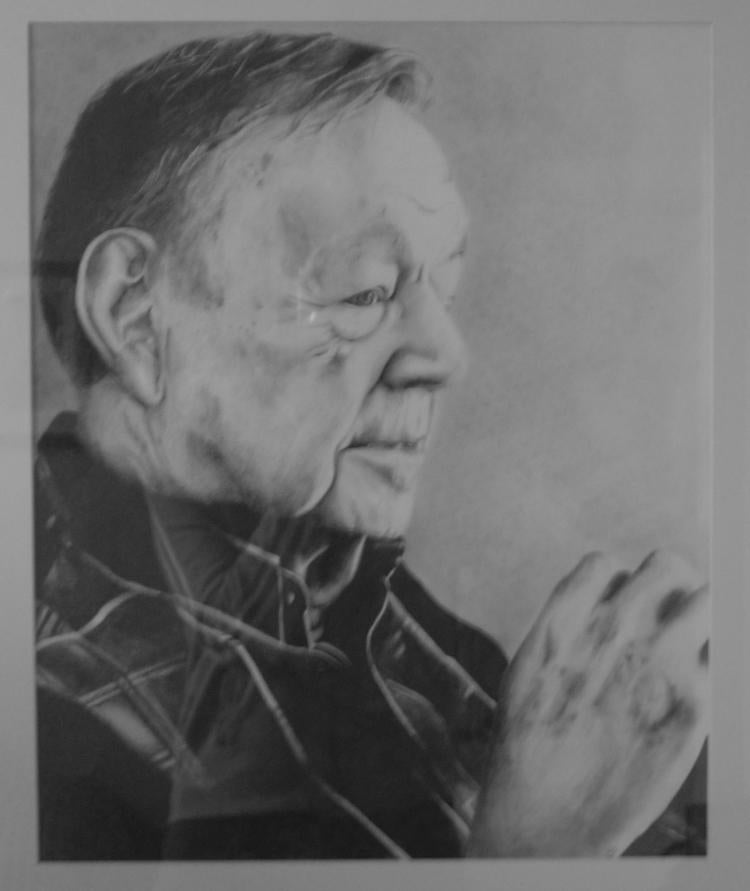

Portrait of Leo Streeter by his granddaughter

Click image to enlarge

Since I was eleven years old and not quite a man, my grandfather moved in with us from town. He came from Norway because of the potato famine; he was nuts about potatoes. He had been a farmer so he was happy to suggest things to grow. We planted radishes, carrots, peas, green beans, yellow beans, lima beans, tomatoes, and corn. In addition to the garden, wild berries grew on our property, free for the picking. We didn’t eat a lot of meat, but we would go fishing, and occasionally the neighbors provided us with venison. We ate better than most people at that time. We weren’t poor; we just didn’t have any money. Despite the lack of cash money, we sure lived well.

Being the new kids in the neighborhood, it was natural for the farm boys to play tricks on us. One of the most vivid incidents was when the other boys packed a knapsack full of rutabagas and sent me to walk through the cow field. Cows love rutabagas, so it wasn’t long before I was running through the field with twenty hungry cows behind me trying to get the rutabagas.

Soon, though, all the kids in the neighborhood were our friends. Our main sports were hunting and fishing. Gophers were fair game since the state paid ten cents a head bounty. In those days, wolves commanded a twenty-five dollar a head bounty. We weren’t that brave, but often thought how nice it would be to get a wolf. Another source of income was shooting blackbirds and pretending they were crows as the crows received a twenty-five cent bounty.

My first present for my twelfth birthday was a single shot .22 rifle. That seemed to be a rite of passage for farm kids in the area. The older boys indoctrinated us into the safety rules for rifles. There were a few accidents, but not with rifles--with dynamite caps. There were a lot of tree stumps to be blasted, so every farm had a supply of dynamite and dynamite caps. One of the boys was too adventurous and had a dynamite cap go off in his hand and take three of his five fingers. But when it came to catching gophers, he was a hero. One way to flush gophers out was to pour water in their hole and he knelt alongside the hole and grabbed the gophers as they ran out.

Yes, we had to go to school. The schoolhouse consisted of three rooms for first to eighth grade in the nearby town of Bennett, Wisconsin. Bennett was home to 213 people. The school bus was an old model T Ford pickup truck with planks across the edge to sit on and a plywood canopy on top.

After school there was much work to be done. Filling up the wood box, pumping water for the night, and on washdays pumping water for the washtub and shaving soap for the laundry. Back in those days, people didn’t buy soap powder; they shaved a bar of white soap into soap powder. Except for the mailman, and the road grader, we didn’t see many people. My mother welcomed the Watkins man every other week and we purchased only one pound of coffee. The mailman came every weekday in his model T Ford delivering the paper, which was our only source of news as we did not have television or a telephone.

We lived on the farm with our faithful dog Sandy, who was part beagle, part poodle. We called him Sandy because the mother-in-law of the man who drew Little Orphan Annie gave him to us while we were living in Chicago. Sandy loved to accompany us on our hunting trips. Another varmint we used to shoot were woodchucks. Sandy was an excellent woodchuck hunter.

My mother grew up on a farm herself. She was an excellent cook and seamstress. She made excellent bread from fifty-pound sacks of flour that were stored in our kitchen. In addition, she canned much of our vegetables and berries. Besides that, we had a root cellar where we stored the potatoes, cabbages, rutabagas, and carrots for the winter.

The village consisted of one church, one school, and the general store. One of the biggest sources of entertainment was the local church, which conducted services on Sundays and Wednesdays. It was a Presbyterian church, but everyone in town came because it was the only one (except for the Catholics, of course.) Our family was Norwegian Lutheran. The church hosted chicken dinners, which normally cost 35¢ but I received a free chicken dinner for hauling firewood. The food was rich: roasted chicken, lots of mashed potatoes, peas and carrots, and pie. In addition, the PTA of the school had Bunco parties every few weeks, and many kids and all the parents came to it. They would serve cake and coffee. One man in town could play the accordion, so he was a source of entertainment at PTA meetings. His musical act was called “Jakey and his Acordine.”

This all ended when we moved into the city so that I could go to high school. This move was not as much of a shock as the previous one. Most people in Superior were of the same economic class and were predominantly Scandinavians. Now that I am really old I still remember the fun I had growing up in Bennett, Wisconsin. This experience of growing up in the country with minimum comforts and no frills has shaped my life.

Leo Streeter with Katherine Pierce

Leo Streeter with Mali Emerson

Click images to enlarge