Policing Black Women’s Sexual Expression: The Cases of Sarah Jones and Renee Cox

[1] The history of black feminist theory relates black women’s sexuality as silence or dissemblance (Hammonds, Hine, Spillers). With continued sexual exploitation of black women and girls, increasing attention to male rape in prisons, misogyny in popular culture, and homophobia in black communities, the discourse of silence reigns supreme, but not unchallenged. Black women’s historians excavated narratives, memoirs, and speeches detailing black women’s victimization, but also their resistance. Yet, exempting recent literature linking black feminism and hip hop, there is little discussion of what it sounds like to speak for black sexuality in progressive, liberating ways. This article asks, what, historically, have U.S. black women had to say about their own sexuality? What have been the sociopolitical reactions to an articulation of black female sexuality? More pointedly, given a history of sexual exploitation, are black women always already defined as sexual outcasts?

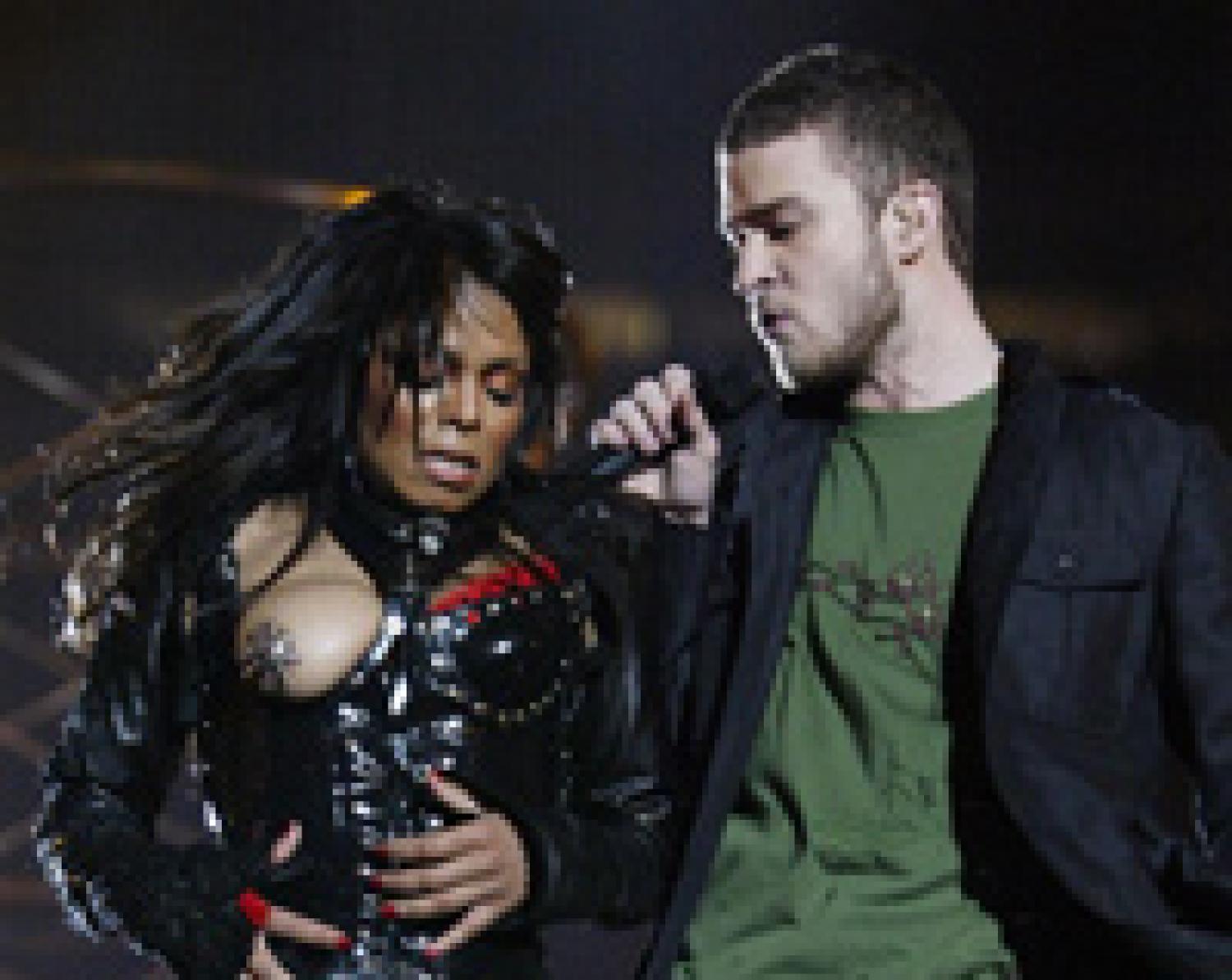

Figure 1: Jackson and Timberlake Wardrobe Malfunction

[2] Close to a decade later, Americans have yet to recover from a moral panic over pop star Janet Jackson’s right breast. Revealed at the National Football League’s (NFL) February 2004 Super Bowl in a stunt that brought “wardrobe malfunction” into the popular lexicon, Jackson and her “nipple shield” (an outlaw sexuality accessory most American parents couldn’t begin to comprehend, much less explain to their children), in a split second, dramatically shifted how live music and film awards shows are broadcast (figure 1).

[3] What was once touted as “live television” now includes a network-imposed three to five second delay in case viewers should see too much liveness. Most immediately, Justin Timberlake, the young, white pop star who ripped off the revealing part of Jackson’s costume, and whose song they performed, “Rock Your Body,” ends with “gotta have you naked by the end of this song,” virtually disappeared from the scandal. In addition to issuing apologies and appearing contrite in public, Timberlake’s handlers situated his role as that of an innocent boy from a good family who was duped into the unfortunate incident. Timberlake’s race (white), geographical roots (Tennessee), and performance history (former Mickey Mouse Club kid) earned him a popular culture pass from further opprobrium. Much like Madonna’s appropriation of black gay male culture and her well-publicized affair with basketball bad boy Dennis Rodman, Timberlake sought “street cred” through rumors that he dated Jackson. Black sexuality can bestow popular culture legitimacy, but there are limits to how far appropriation can venture into the Land of the Other. Post-Super Bowl, Jackson, who Timberlake had previously credited with recognizing his talent and lifting him from boy band obscurity, went from nurturing “Pop Mammy” to “Conniving Jezebel” in the bodice rip heard ‘round the world.

[4] The incident moved the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) the governmental body responsible for regulating U.S. media broadcasting and sales, to launch its own “shock and awe” campaign to increase fines and vigilance against “the increasing coarseness on television and radio” to protect our “unsuspecting children” (Powell, 2004). But, before Janet Jackson’s Super Bowl “costume reveal,” the FCC was alarmed and moved to censorship by a lesser-known black female performance artist.

[5] This article deals with the struggle over black women’s sexual self-definition using two cases of attempted censorship: the FCC’s censorship of poet Sarah Jones’s single “Your Revolution” and New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani’s attempt to form a city-wide decency commission in reaction to, in part, artist Renee Cox’s photograph Yo Mama’s Last Supper (figure 2).

Figure 2: Renee Cox, Yo Mama’s Last Supper. 1996.

These two works give voice to black women defining their sexual subjectivity. By sexual subjectivity, I mean articulations (e.g. writings, songs, performance, fine art, speeches, etc.) that permit black women to speak on their own terms about who they are as sexual beings, which sexual acts they enjoy (doing and having done), how they relate to their bodies, and myriad expressions that fall within the bounds of sexuality. I believe Jones and Cox’s expressions of black women’s sexual subjectivity, move forward studies in U.S. black women’s history and culture that seem stuck solely in a narrative of silence and objectification. Caveat: this is not an attempt to place black women in the post-feminist or sex positive feminist rubric. While I oppose the notion of ”victim feminism” I also adamantly oppose characterizing this project as “post” anything. The former is a politically conservative backlash conceptualization that ignores women’s resistance to oppression, while the later assumes that racial and gender oppression no longer exist.

[6] Instead, this work takes up the question Tricia Rose asks in her book Longing to Tell: Black Women Talk About Sexuality and Intimacy(2006). Through oral history interviews, Rose explores, “how has the history of race, class and gender inequality in this country affected the way that black women talk about their sexual lives”(ix)? Too often, scholars assume that black women do not tell, they show: suffering silently or showing tits and ass in music videos. This project offers one response to Rose’s question by melding perspectives on the construction of black female sexuality, cultural studies, and feminist theory to actually seek black women’s articulations through the popular and fine arts as they engage historical questions of sexual objectification. In addressing these historical antecedents, black women artists are looking to define a way forward, a fulfillment of a holistic sexuality.

[7] I begin with a brief historical contextualization of external definitions of black women’s sexuality. Tracing the economic and social imperatives that lie behind construing black women as eitherasexual Mammies or licentious Jezebels, I delineate the theoretical frameworks used to discuss---or silence---black women’s sexual subjectivity. This outline is then followed by a description of the 2001 FCC’s censorship of KBOO Community Radio and Sarah Jones and Giuliani’s 2001 attempt to use Cox’s photograph for a larger, more repressive campaign begun long before the exhibit featuring Cox’s work debuted. I conclude with the implications of historical silence around black female sexuality as it aids and abets continued attempts to stifle expressions of black female sexual subjectivity that are self-defined. In essence, black women’s sexual expressions are censored if they are not in line with keeping Black women’s bodies in service to an economy based on exploitation.

[8] Overall, I maintain that black women are making strides in overcoming historical silences around Black women’s sexual agency. However, misguided governmental paternalism and/or religious hysteria hamper this progress. This paternalism is assisted by the black community’s willingness to embrace commodified heterosexuality, while ignoring non-mainstream or queered sexualities.

Still Moppin’ with Dirty Water

[9] As it stands now in U.S. black women’s historical accounts, collectively and individually black women maintained silence around their sexuality in response to generations of sexual assault and forced reproduction in slavery. Through what historian Darlene Clark Hine (1998) calls a “culture of dissemblance” black women hid much of what had been exposed, exploited and deemed the property of the slaveocracy---their bodies and psychic lives---through silence or denial. They wore masks that revealed nothing to perceived enemies, but also little to trusted family and friends. But also the nineteenth century black women’s club movement, consisting of mostly middle class elites, played a significant role in this dissemblance. Post-emancipation, and excluded from Victorian ideals of womanhood (piety, purity, submission, domesticity), nineteenth century black women sought an identity defined by a politics of respectability, or a place of virtue and morality that left little room for asserting a self-defined black female sexuality. Notably, 1960s narratives of black-white intimate relationships during the civil rights movement and the 1970s sexual revolution consist mostly of white women’s memoirs of sexual freedom or sexual exploitation, as well as black men’s assertions, such as Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice (1968), of a new black masculinity through sexual conquest. Black women’s assertions to sexuality during this period are mostly confined to resisting another kind of coerced reproduction: having babies for the revolution. By the time we enter the 1980s and 1990s, black women’s voices are mostly absent while their bodies are displayed as props with as much narrative value as Cristal champagne, Bentleys, and bling.

[10] The result of these public uses of black women’s bodies, but not voices, has been a persistent silence in service to community. In her oft-cited and critical essay, “Interstices: a Small Drama of Words,” literary critic Hortense Spillers describes black women as, “the beached whales of the sexual universe… awaiting their verb” (74). Evelynn Hammonds goes further commenting on the empty space that constitutes Black women’s sexuality and their bodies as, “always already colonized” (171).

[11] A contemporary case in point: the coming out story, as it were, of 78-year-old Essie Mae Washington-Williams. Following the December 2003 death of rabid segregationist Strom Thurmond, Washington-Williams revealed that she was his biological daughter. Until the day he died, Thurmond was virulently opposed to anti-racist local, state and federal initiatives. Thurmond split ranks with the Southern Democrats when they adopted an integrationist platform and ran for president in 1948 as a States’ Rights Democrat. He was, in essence, an unrepentant racist. Yet, he provided financially for Washington-Williams’ childhood, paid for her college education, corresponded with her regularly, and allowed his daughter to visit him in Washington, DC to the full knowledge of his senatorial staff. The popular media mostly focused on constructing Washington-Williams’ silence as the noble, selfless silence of a woman who, in her own words, did not want to jeopardize Thurmond’s political career nor embarrass his (white) family: “I am Essie Mae Washington-Williams and, at last, I feel completely free” (Gettleman, 2003). The historical resonance in that statement---that it took Thurmond’s death to figuratively free Washington-Williams---is significant.

[12] Mostly omitted from media narratives is the deployment of selective silence: on the part of all parties: Washington-Williams, Thurmond, her mother Carrie Butler, and those around them who kept their secret. Each of these silences, with varying motivations, “speak” volumes to the possible sexual assault involved in Washington-Williams’ conception. The problems with this version of events are, of course, manifold: there is likely no one living that can attest to the exact nature of Thurmond and Carrie Butler relationship. Was it forced or was it consensual? As a persistent echo of debates around the nature of Thomas Jefferson’s sexual relationship with enslaved African Sally Hemings, what is the probability that a 22-year-old, white, Southern male sexually assaulted his 16-year-old, black, live-in housekeeper in a culture where sex with the black “help” was considered a coming of age ritual, an obligation of servitude not far removed in degree from that of nursemaid? Cultural critic Michael Eric Dyson captured the paradox this drama plays out for a culture where blackness (and I would add black female sexuality) is “dissed and denigrated, on one hand, and elevated and pursued, on the other” (Dyson, 2003). Yet, we might also ask of Hemings and Butler’s situations, is there room for consent? Where might we find black female sexual agency in a culture of dissemblance? Is it, in a sense, blasphemous to question the vagaries of desire as lived and experienced under power imbalances?

[13] African American and women’s cultures are resistive and black women, resisting race and gender oppression, do find ways to establish, as Hammonds suggests, a “politics of articulation” that navigates the pleasures and dangers of sexuality (180). Hazel Carby (1994), in her essay, “It Jus’ Be’s Dat Way Sometime: the Sexual Politics of Women’s Blues” and Angela Davis, in her book Blues Legacies and Black Feminisms (1998), cogently analyze the evidence of feminist consciousness in blues singers’ writings and renderings, so it is worth noting Smith and Rainey’s early articulations of black female sexual subjectivity. This article returns later to examples of these articulations but for the moment it is sufficient to remain mindful that blues women defied externally imposed stereotypes and community-imposed silence through their music and public lives. Blues women, in effect, set precedence for artists such as Sarah Jones performing in a distinctively African American genre: hip hop.

“The FCC won’t let me be!”---Eminem

[14] On October 20, 1999, KBOO, a community-sponsored, volunteer-run radio station in Portland, Oregon, aired Sarah Jones’ poem “Your Revolution” (see lyrics) on its underground hip hop/rap show, The Soundbox. Jones’ poem, loosely based on protest poet Gil Scot Heron’s “Your Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” created a collage-like response to male artists’ objectifications of women’s bodies. Jones, while embracing hip hop as an “incredibly powerful cultural movement,” sampled misogynistic lyrics and transformed them into a confrontational feminist statement about black female sexuality (Colorlines, 2001) Jones quoted directly from songs by popular rap artists LL Cool J, the Notorious B.I.G., and Shaggy that mainstream radio stations played on high rotation without incident. The original songs sold half a million copies or more.

[15] Unbeknownst to the KBOO disc jockey for The Soundbox, a disgruntled former volunteer routinely taped and submitted the tapes of the show to the FCC for review. The complainant maintained that the show flouted the FCC’s rules against “dirty” words, or indecent language. Several songs from The Soundbox’s1999 broadcasts were submitted for FCC review but it wasn’t until February 2001 that KBOO received an FCC notice alleging indecent language in The Soundbox.

[16] The time frame of the complaint and the FCC’s actual notification of the complaint are significant. KBOO aired Jones’ song---again, one among many the complainant submitted---in 1999, but they received no notice of a complaint until almost a year and three months later. Why the delay until 2001? One possible explanation is the ascension of a new conservative head to the FCC.

[17] The president appoints, and the U.S. Senate approves, five FCC commissioners. George W. Bush appointed Michael C. Powell, son of Secretary of State Colin Powell, to FCC chair in January 2001. The FCC---an entity created by the Communications Act of 1934 to safeguard the airwaves as a public trust---was under the direction of Michael Powell who proclaimed in a USA Today interview, “My religion is the market” (Davidson, 2002). Moreover, though the words “public interest” are used in the Communications Act approximately 103 times, in a speech he delivered to the American Bar Association, Powell admitted to lacking a grasp of the meaning of public interest (Powell, 1998). Some viewed Powell’s appointment to FCC chair as the death knell of independent media and a boon for corporate media consolidation. KBOO’s staff and supporters perceived the delayed FCC censorship under Powell as but one warning to non-corporate radio interests that the days of independent, non-commercial radio were numbered.

[18] Returning to the complaint against KBOO, by May 2001, all FCC complaints were dismissed except for one song---Jones’ “Your Revolution.” The FCC maintained that the song “contain[ed] unmistakable patently offensive sexual references” that pandered to indecency (FCC, 2001). The FCC defines indecent speech as “language that, in context, depicts or describes, in terms patently offensive as measured by community standards for the broadcast medium, sexual or excretory activities or organs” (Ibid). The commission fined KBOO $7000. The radio station appealed the fine on the grounds that the “FCC’s characterization of the song betrays a deep political and cultural ignorance” (Lee, 2001). Ironically, the complainant who submitted The Soundbox recordings to the FCC, lamented the choice of Jones’ “Your Revolution,” saying “I wish they had at least picked a misogynistic song, and not an anti-misogynistic song” (Jones v. FCC, 2003). Jones had, incidentally, been invited to perform this particular poem at over 60 high schools, feminist benefits, and international women’s gatherings in 2001.

[19] After waiting eight months for a decision on KBOO’s appeal, Sarah Jones, with assistance from People for the American Way, an organization dedicated to ideals of democracy and pluralism, filed her own lawsuit against the FCC for violating her First Amendment rights. Jones maintained that by labeling her poem indecent the FCC’s ruling, “damaged her reputation and livelihood and is chilling broadcast of certain music” (Jones v. FCC and Powell). Six months later a district judge ruled that, as the FCC had not yet issued a final ruling, Jones’ claim was outside the district’s jurisdiction.

[20] Following this court decision, Jones appealed the jurisdiction claim, but her lawyers also filed an informal request directly to the FCC to rescind the indecency verdict. Noting the FCC’s violation of its own regulations to respond to appeals within 60 days, her lawyers argued that three years and sixteen months after KBOO’s broadcast Jones continued to suffer the consequences of an indecency label.

[21] In February 2003 KBOO received notice that the FCC repealed the indecency decision and the fine. One can only hypothesize that Jones’ appeal was the catalyst. The FCC concluded that, “While this is a very close case, we now conclude that the broadcast was not indecent because, on balance and in context, the sexual descriptions in the song are not sufficiently graphic to warrant sanction. For example, the most graphic phrase (‘six foot blow job machine’) was not repeated” (“Memorandum Opinion and Order,” 3). The decision also cited the performance of “Your Revolution” in schools as evidence considered.

[22] Despite the free speech victory, there were significant costs for defending “Your Revolution.” First, though the fine was $7,000, KBOO spent $24,000 of its supporters’ contributions, not government funds, defending the station against the ruling. The KBOO Board of Directors decided, after much contentious debate among station volunteers and staff over the political merits of hip hop, that it was better to stand up to the FCC and hope for victory than to be labeled the station that aired a dirty song. Still, to this day the case is remarked upon at the station as an example of “the trouble with hip hop” and not “the trouble with censorship.”

[23] We must also take into account the implications of an indecency label for Jones. Despite its repeal, such an action is much like a daily newspaper’s corrections of mistakes: the initial mistake makes the front page while the correction is often buried on page six. People are more likely to remember the initial FCC indecency ruling than to ever hear about its repeal. Yet, I maintain that being the lightning rod for this particular case of First Amendment rights heightened Jones’ profile. This dubious benefit of censorship was not lost on Jones. She admitted, “It doesn’t really make me happy that radio stations are reluctant to play my song. But believe me, I’m going to turn this into a positive. I’m excited to reach some new ears with the work. When you ban something, it piques people’s curiosity” (Richardson, 2003). At the same time Jones’ work was censored, the FCC also cited and rescinded a fine against a Colorado radio station that played the censored version of Eminem’s “The Real Slim Shady” from his The Marshall Mathers LP (2000). The Eminem case created a high profile and positive juxtaposition for Jones’ feminist response to rap misogyny. Jones’ case and subsequent victory over the FCC undoubtedly made her a hip hop feminist heroine in progressive circles resulting in accolades for her later work.

“Disgusting,” “Outrageous,” and “Anti-Catholic”: Sight Unseen

[24] Even before the exhibit opened its doors, the Brooklyn Museum of Art’s (BMA) exhibit of 94 black photographers grabbed international headlines: “’Naked Jesus’ Angers Giuliani” and “Affronted by Nude ‘Last Supper,’ Giuliani Calls for Decency Panel” (BBC, 2001; Croft, 2001). The exhibit, Committed to the Image, included photographer Renee Cox’s satirical restaging of da Vinci’s Last Supper with striking differences. In five Cibachrome prints, Jesus’ eleven disciples are black, Judas is white, and Cox herself stands in as Christ---nude, arms spread, direct in her gaze. If Olympia’s Maid was a departure from previous depictions of the female nude because its female focus returned the male gaze, Cox’s female Jesus was unrelenting in her’s.

[25] After the controversy was underway, Cox explained her intentions in print and television forums. Her Last Supper was part of a series titled “Flipping the Script” in which Cox also re-visions Michelangelo’sDavid as a black afro’d male, the Pieta with herself as the nude Virgin Mary, and The Expulsion of Adam and Eve. Of these images she notes her intention to challenge women’s (lack) of position in the Church through a critique of Catholicism and the Church’s response to slavery. Cox also wanted to take on the invisibility of African-Americans in art---notably the lack of a black presence in Renaissance art. In an interview, Cox states that her work “becomes a protest” but is “more about critique” (Croft, 2001). This is an important distinction and one that highlights how Cox’s art moves black women’s sexuality from protest to critique on through to subjectivity. While marginalized peoples might protest their exclusion, they do so from the outside looking in. As critique, Cox uses her own body and refuses to be on the outside. She demands inclusion. She makes and takes space. Noting the prevalence of nude bodies in classical Greek and Roman imagery in cathedrals and murals, Cox states, “[There are] religious images with penises and tits all flung up on the ceiling…” What makes her work different, and I would add controversial, is that “a black woman…has dared to put herself at the head of the table” (Gottwaldt, 2003).

[26] Much like his reaction to BMA’s 1999 exhibit Sensation, which included London-based artist Chris Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary, in which he uses elephant dung as but one part of his medium, Giuliani’s response was immediate and disproportionate to any reactions these works encountered in previous displays. In reaction to SensationGiuliani immediately threatened to: withhold city funding which accounted for approximately one-third of the BMA’s operating budget; terminate the museum’s lease; and to wrest control of the museum from its curator, director, and board. Giuliani’s actions were overturned in federal court on the grounds that he was attempting to violate BMA’s freedom of expression. Still, in reaction to Sensation and theLast Supper, Giuliani announced the formation of a citywide decency commission. The commission’s remit was to set standards determining whether particular works of art or exhibits were “an affront, an attack, or a debasement of religion, ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, or gender” (Giuliani, 2001).

[27] Cox’s reaction, the New York arts community, and civil liberties organizations, too, was immediate. Cox, like the depictions in her photographs, was direct and unrelenting in defending her Catholicism and her right to critique the Church. She was also pointed in noting the Mayor’s hypocrisy and indecent behavior citing revelations that Giuliani had an extra-marital affair and his failure to inform his wife of his intentions to divorce her before he told the press. Cox sniped, “now that’s he’s been busted with the other woman, I wouldn’t be talking about moral issues” (Garcia-Fenech, 2001). Cox aligned Giuliani’s creation of a decency task force with mass book burnings in Nazi Germany, but ultimately directed Giuliani to “Get over it” (Bumiller, 2001).

[28] New York arts institutions and the New York Civil Liberties Union spent the summer of 2001 protesting the decency commission and Giuliani’s continued assaults on free speech under the guise of protecting the Church from “anti-Catholic” bias. With the events of September 11th, Giuliani was transformed from law & order tyrant to mayoral hero-leader literally overnight, his campaign for decency fell by the wayside, and the decency commissioners’ terms ended in 2002. Giuliani’s mayoral successor, Michael Bloomberg, kept his promise to disband the commission and reinstated what was formerly a citywide cultural affairs commission to promote, rather than censor, the arts (Bloomberg, 2003).

Black Female Sexuality as Excess

[29] The initial censorship of Sarah Jones’ “Your Revolution” and attempts to censor Renee Cox offer contemporary insights into my opening question about articulations of black female sexuality: are black women always already defined as sexual outcasts? Scholarship in Black women’s studies traces the ways in which sexual exploitation in slavery resulted in black women choosing silence rather than struggle to define their own sexuality publicly. Black women did, in fact, participate in a form of feminist resistance to gender oppression under slavery. They fought back physically, emotionally and spiritually against rape and forced reproduction with tactics often not recognized as guerilla warfare (e.g. herbal abortifacients, infanticide, poisoning, escape). White supremacy constructed black women as always available and hypersexual to allege the impossibility of the rape. Today that construction persists as exhibited by the mock violation of Jackson at the Super Bowl, but extends the “privilege” of the violation of black women’s bodies to black patriarchy. For evidence, note the 1995 Harlem parade held when pugilist Mike Tyson was released from prison after serving time for sexual assault. Or the way some African Americans persist today in uncritically rallying around R&B singer R. Kelly---arrested twice---in light of revelations of his alleged exploits with a minor and child pornography. Witness the recuperations of Michael Jackson’s blackness as he attempted to fight more allegations sexual abuse allegations and in the aftermath of his unexpected death. Is it any wonder that Black women and girls historically chose silence around sexuality that has been, and continues to be, defined as too much, as excess?

[30] From blues to hip hop there are articulations of black female sexuality, but the efficacy of those articulations is conflicted and contentious. When Bessie Smith, in 1929, likened her desire for open sexuality to candy and exhorted her lover, “Sweet as candy in a candy shop/Is just your sweet sweet lollypop/You gotta give me some, please give me some/I love all day suckers, you gotta give me some,” middle class African American mores marginalized this expression and considered her risqué. When hardcore rappers Lil’ Kim or Trina sang the same sentiment as Smith, but with expletives considered vulgar, they offended African American mores among black middle-and working classes.

[31] The difference between Bessie Smith and Lil’ Kim’s articulations, I contend, is the shift in black investment in black women’s sexual marketability. During the height of the blues women era, black women experienced a level of freedom that one might suggest was actually apositive result of segregation. Until the nascent, white-run recording industry recognized blues artists’ labor could produce a profit recording “race records,” blues singers truly lived on the cutting edge of articulating the meaning of freedom for African Americans. Bessie Smith, for example, sold over two million copies of her first recording, “Down Hearted Blues,” in its first year of release. As the highest paid black entertainer in the mid-1920s, Smith’s money came from her road shows, not the millions of records she sold. Still, independent of record companies, women like Smith lived hard and sang about those experiences without censorship, on their own terms. They also exerted a newfound economic power by spending their money, not unlike their mainstream hip hop descendants, on furs, jewelry, clothes, and---for many blues women---other women.

[32] Today, female rappers, hip hop artists, and R&B singers are constructed for mass consumption by recording label executives, managers and lawyers. In one of the most astute statements on the Timberlake-Jackson Super Bowl incident, Carla Williams note the hypocrisy in the culture industry:

If, however, we don't take Jackson's explanation at face value and agree with the pundits who insist she intended to show all, then why shouldn't she be the one in control of how her body gets displayed and sold? What Jackson did, intentionally or not, is make glaringly obvious what's been happening all along in her career as she's been carefully cultivated as a sex symbol with fewer and fewer clothes on, up to her last album cover on which she reclines covered only by a bed sheet. It was fine if her record company was selling her sexuality and no one was complaining, but when the public finally cried foul everyone backed away to leave her twisting alone in the media wind. So now Janet solely is to blame. It's a familiar trope in American culture-the oversexed black woman, now even willing to whip her tit out on national television to sell some records. She surely has to be stopped (Williams, 2004).

To be clear: some of the industry people Williams mentions are African Americans complicit in perpetuating stereotypes about African American sexuality in the interest of profit. Whether they are the artists themselves or male record industry executives (white and black), only very specific articulations of black women’s sexuality make it to the desks of radio programmers, to the listening public, and into the pages of popular periodicals. Those mainstream articulations feature black women’s bodies divorced from self-directed sexuality.

[33] FCC censorship of Sarah Jones’ “Your Revolution” highlights the hypocrisy of U.S. views of black women’s sexuality. Jones’ poem is clearly, in context, a rebuttal to mainstream hip hop’s misogyny and sexism. She is also asserting a black female sexual agency that says to men she considers brothers and lovers, you will not determine my fate---sexual or otherwise. By rescinding their ruling the FCC is essentially claiming, in basketball terms, “no harm, no foul.” That is not, in fact, the case. I would argue that through its initial actions and the length of time it took to correct their mistake, the FCC implicitly sanctioned disarticulations of black women’s sexuality that were infinitely more damaging, but profitable to the culture industry. Had FCC commissioners any awareness of hip hop’s political roots, in 1980s-era urban de-industrialization or the full breadth of hip hop as a cultural movement, or even the temerity to consult scholars researching and teaching hip hop, perhaps they might have been able to distinguish between pandering to indecency and issuing a challenge for real respect around issues of sexuality, pleasure, and music.

[34] State reactions to the black female body are, of course, contextualized: also part of the “Committed to the Image” exhibit was Willie Middlebrook’s The God Suite, Pomp No. 628, which also displayed a black women, nude from the waist up, arms extended as if crucified. Whether Cox’s photo merely played into Giuliani and the Catholic League’s anti-Catholic hysteria, becomes intertwined with willful ignorance about the nude in art and hostility to the black female body. That Cox chooses to use her body in her art was a recurring theme in the press generated by the controversy. One woman on theCNN Morning News opined, “She could have made her statement with her clothes on, certainly. I don’t understand the nudity” (CNN, 2001).

[35] I would also argue that censorship of Cox’s photography extended to the degree and ferocity of interrogation she experienced. Inquiry ranged from non-sequitor (“But it’s not just any body. It’s your very good-looking, sexy body,” remarked one Salon reporter) to the inane (from the same reporter, “Would you use yourself if you weren’t so good-looking?”) (Croft, 2001). In all cases, the subtext seemed to question Cox’s right to display her body in her work. What gives Cox, as an artist, license over how she uses her body? It’s a queer line of inquiry. Cox rightly observes that were she not to use her own body she would have to deal with accusations of exploitation. Instead, Cox’s representations that feature her own body are labeled narcissistic.

[36] In a culture rife with restrictive dualisms such as good/bad, dominant/subordinate, it is only acceptable that black women’s sexuality be cast as asexual or hypersexual. An assertion of black female sexual agency that makes black women accountable only to themselves is dangerous and unwanted in American culture because under capitalism it is not profitable. For an empowered black female sexuality to be productive, black women and black communities must benefit from an eroticism that is not merely exploitative or masquerading as liberated, but that articulates a black female sexual subjectivity that is stimulating, provocative and conducive todisassembling the culture of dissemblance.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge the support of the U.K. Arts & Humanities Research Leave Grant and the helpful comments of the Genders anonymous reviewer.

Works Cited

- BBC News. “Naked Jesus Angers Giuliani.” 16 February 2001.

- Bloomberg, Michael. Campaign Accountability Statement. 10 February 2003.

- Bumiller, Elisabet. “Affronted by Nude ‘Last Supper,’ Giuliani Calls for Decency Panel.” New York Times. 16 February 2001.

- CNN Morning News. “Controversy Rages Over Artists’ Depiction of Jesus as Nude Woman.” 16 February 2001.

- Cox. Renee. Artist’s website. www.reneecox.org.

- Croft, Karen. “Using Her Body.” Salon. 22 February 2001.

- Davidson, Paul. “FCC Chief Powell Believes in Free Market.” USA Today. 5 February 2002.

- Dyson, Michael Eric. “Commentary: Thurmond’s Daughter.” The Tavis Smiley Show. National Public Radio, 18 December 2003.

- Evans, Sara. Personal Politics: the Roots of Women’s Liberation in the Civil Rights Movement and the New Left. New York: Vintage Books, 1980.

- Federal Communications Commission. “Notice of Apparent Liability for Forfeiture.” 14 May 2001.

- ---. “Memorandum Opinion and Order: In the Matter of The KBOO Foundation.” DA 03-469. 2003.

- Garcia-Fenech, Givoanni. “Giuliani’s New Crusade,” artnet. 16 February 2001.

- Gettleman, Jeffrey. “Final Word: 'My Father's Name Was James Strom Thurmond'.” The New York Times. 18 December 2003.

- Gottwaldt, Russell. “Deconstructing Race and Pissing Off Giuliani.” F Newsmagazine. April 2003.

- Giuliani, Rudolph. “The Rights and Responsibilities of Public-Funded Cultural Institutions.” The Mayor’s Weekly Column. Archives of Rudolph W. Giuliani.

- Hammonds, Evelynn. “Toward a Genealogy of Black Female Sexuality: the Problematic of Silence,” in Feminist Genealogies, Colonial Legacies, Democratic Futures. Eds. M. Jacqui Alexander and Chandra Talpade Mohanty. New York: Routledge, 1997. 170-182

- Hine, Darlene Clark. “Rape and the Inner Lives of Black Women in the Middle West: Preliminary Thoughts on the Culture of Dissemblance,”Signs 14 (August 1998): 912-920.

- Jones, Sarah. Artist’s website. www.sarajonesonline.com.

- Lee, Chinsun. “Out Loud and Proud: Sarah Jones as Herself.”ColorLines. Summer 2001.

- ---. “Counter ‘Revolution’.” Village Voice. 20-26 June 2001.

- Powell, Michael K. “The Public Interest Standard: a New Regulator’s Search for Enlightenment,” American Bar Association 17th Annual Forum on Communications Law, Las Vegas, 5 April 1998.

- ---. Testimony to the U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, 11 February 2004.

- Richardson, Lynda. “A Diva of the Spoken Word Who Irritates the FCC.” The New York Times. 12 July 2001.

- Sarah Jones v. Federal Communications Commission and Michael Powell. Opinion and Order. 4 September 2002.

- Sarah Jones v. Federal Communications Commission. Appeal. 24 January 2003.

- Smith, Bessie. You’ve Got to Give Me Some. 1929.

- Spillers, Hortense. “Interstices: a Small Drama of Words,” in Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality. Ed. Carol A. Vance. London: Pandora, 1992: 73-100.

- Williams, Carla. “Body Baggage.” New York Newsday. 8 February 2004.